Fantasies

The Fentanyl Hysteria: Fact and Fiction

Why myths surrounding the drug parallel the fears around MSG.

Posted January 18, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

In the late 1960s, Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok sat down for a meal at a Chinese restaurant. Afterward, he complained of numbness and wrote a piece in the New England Journal of Medicine in which he described his symptoms. This would spark a flurry of reports from people describing a series of symptoms they experienced after eating Chinese food—heart palpitations, headaches, numbness, etc. At one point, even “irreversible brain damage” was listed as a possible outcome. This phenomena came to be known as “Chinese restaurant syndrome” and became associated with the chemical monosodium glutamate, more commonly known as MSG.

We now know that Chinese restaurant syndrome doesn’t exist. Repeated studies have shown that MSG is safe to eat and studies that compared MSG to a placebo found that people exposed to the placebo also developed symptoms. But the damage was done: Hundreds of restaurants now boast “No MSG” and “MSG Free” labels on their storefronts and menus. MSG can be found in practically every processed food there is; however, only Chinese food is singled out for scrutiny.

What does MSG and a false syndrome have to do with the opioid crisis? The hysteria behind “Chinese restaurant syndrome” bears parallels to what we see playing out today with beliefs about fentanyl. Sometime around 2015, when it was clear that the powerful opioid was adulterating the drug supply, in an effort to educate the public about the dangers of the opioid a picture began to circulate featuring lethal doses of heroin and fentanyl, contained in vials side by side. A few grains of fentanyl were contrasted with a moderate amount of heroin to underscore just how easy it is to overdose with the former drug. The use of this image, while powerful in communicating the dangers of fentanyl-related overdose, may have come with some unintended consequences.

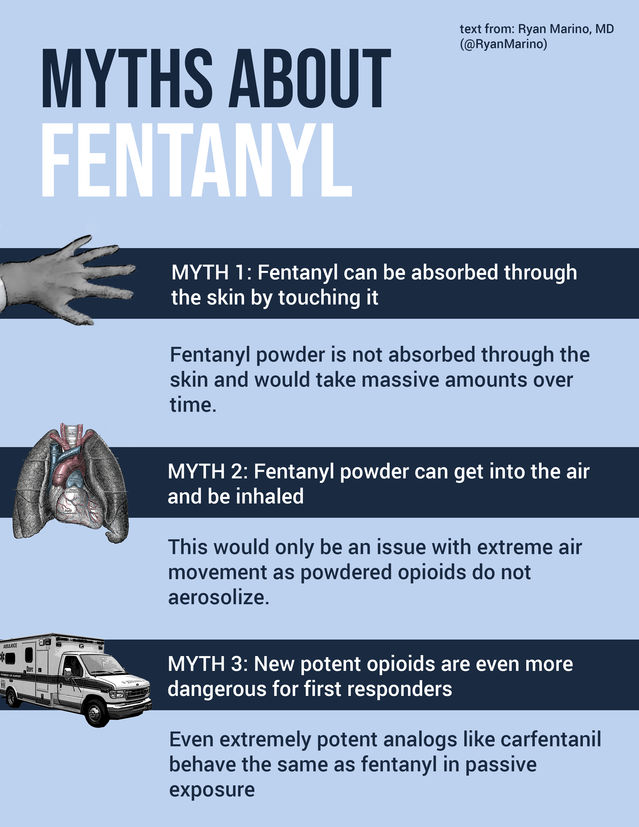

Over the last few years, there have been a flurry of reports, primarily from law enforcement, of adverse reactions to accidental exposure to fentanyl. Sometimes, these are reported as “overdoses." Reactions include everything from sweating to lightheadedness and headaches to fainting. Officers usually report that powdered fentanyl either became airborne, or that they came into contact with it unknowingly through touching. But how true is this? Can you really overdose or experience symptoms if you merely touch or inhale fentanyl? To address these concerns, the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT) put out a position paper in which they outlined clearly that airborne and dermal exposure to fentanyl does not represent a realistic threat to a person’s safety. There are exceptional situations where this can happen, but they are rare.

Unlike MSG, fentanyl is legitimately dangerous and can kill someone if used for injection drug use. However, like MSG, the false rumours around fentanyl can have discriminatory and adverse consequences on a group of people: people who use drugs. When the public and law enforcement believe that fentanyl is dangerous, the safety of the person who has overdosed becomes a secondary concern. People may not want to intervene in an overdose, for fear of overdosing themselves. Law enforcement and first responders may take unnecessary precautions when time is of the essence. This myth is so dangerous and pervasive that until early last year, I believed you could overdose from touching fentanyl.

Fentanyl has become an anthrax-like boogeyman. It is frequently described like a weapon of mass destruction, deadly enough to kill thousands of people. New cottage industries have popped up in the security sector, advertising fentanyl-proof gloves and other materials to police departments and first responders. This is extremely concerning and runs counter to the goals of treating drug use as a public health issue. We are treating fentanyl like it is a weapon.

Fifty years after the letter was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, some people are still afraid of eating MSG. There is a great risk that the myths surrounding overdosing and adverse reactions to passive exposure to fentanyl will persist and interfere with efforts to tackle the overdose crisis. Public health officials need to educate the public on the actual risks: Fentanyl is a drug that can be deadly to those who use drugs. It is not deadly to those witnessing and intervening in an overdose.