Genetics

Is Science Value-Free? An Experimental Study

An experiment on more than 1,000 scientists looks at the role of value judgments

Posted December 27, 2012

Imagine that scientists are trying to understand how people develop a particular trait, which they have come to call Trait X. The scientists have discovered a surprising fact about people’s genes. They have discovered that people’s genes work in such a way that almost everyone will end up developing Trait X. In fact, it turns out that children develop Trait X as long as their parents sometimes offer them at least a decent level of treatment.

Now, just about everyone’s parents offer them at least a decent level of treatment at least sometimes. So, given the way people’s genes work, just about everyone actually does develop Trait X.

Ok, now that you've read through this story, ask yourself whether you agree with the following statement:

- Trait X is innate.

Once you've answered this first question, try considering a case that is almost exactly the same, except that the moral significance of the parents' act has been switched around (changes indicated in italics).

Imagine that scientists are trying to understand how people develop a particular trait, which they have come to call Trait X. The scientists have discovered a surprising fact about people’s genes. They have discovered that people’s genes work in such a way that almost everyone will end up developing Trait X. In fact, it turns out that children develop Trait X as long as their parents sometimes treat them badly.

Now, just about everyone’s parents treat them badly at least sometimes. So, given the way people’s genes work, just about everyone actually does develop Trait X.

And now consider the corresponding sentence:

- Trait X is innate.

My coauthor Richard Samuels and I wanted to know how people thought about questions like this one, so we tried running a series of systematic experimental studies. First, we tried giving these cases to ordinary folks. What we found there was something quite surprising. It seems like the only difference between the two cases lies in their value (one involves something good, the other something bad), but people ended up responding to the two cases in very different ways. In the first case, they tended to say that the trait was innate, whereas in the second, they tended to say that it was not. In other words, this difference in value -- a difference between good environments and bad environments -- seemed somehow to be affecting their intuitions about whether a trait was innate or acquired.

But what if we turn to professional scientists? Surely, scientists have a more sophisticated way of thinking about issues like this one, so it seems like we should predict that they will show no difference at all between the morally good case and the morally bad one.

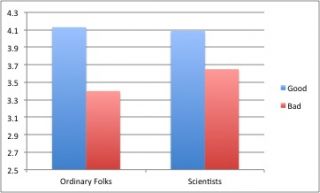

To address this question, we recruited more than a thousand scientists (biologists, psychologists, linguists, etc.) and tried running the study on them. But we then ended up finding an even more surprising result. Oddly enough, the scientists responded just like the ordinary folks! In fact, when we asked them to rate the innateness of each trait on a scale, the results came out like this:

This result seems to be suggesting something interesting about the way scientists understand these issues. It's easy to find oneself thinking that scientists have some highly technical way of resolving these questions -- a special method in which value judgments play no real role -- but what we find here is exactly the opposite. Scientists are human beings, after all, and like any other human being, it seems that scientists can be swayed by their value judgments.

[In case you are curious, the actual academic paper -- published in Cognition -- is available here.]