Intuition

Your Intuition is Broken: When to Change a Winning Horse

Why and when it pays to ignore your gut feelings.

Posted September 22, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Repeating whatever has worked before can be intuitive, but it can also be wrong.

- People confuse success and failure with the reasons behind them.

- Thinking a bit longer can let you see the traps.

Never change a winning horse. If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it. If it worked, do it again. Intuitive, right? It can also be very, very wrong.

Imagine a firm facing an upcoming complex negotiation with a supplier. Unfortunately, Ann, the firm's experienced negotiator, is sick. The firm has to send a rookie instead—Bart, with a list of objectives in his pocket. But Bart does a good job! Three-quarters of all objectives are met. Everybody is happy.

One month later, a similar negotiation with a different supplier is coming up. Ann is now recovered. The CEO looks around the table and asks, “Who should we send?” Almost immediately, somebody says, “Well, Bart did a good job last time, so why not send him again?” Everybody nods.

What has just happened? Was there a careful evaluation of pros and cons, an estimation of possible consequences and their likelihoods? No. This is just reinforcement. We chose option “Bart.” We won. Hence we choose it again.

Reinforcement is the very basic human tendency to repeat whatever has worked in the past and avoid what has not. This is how our brain is wired and, mostly, this is how we learn. Touch the fire once, and you will not touch it again. Makes sense.

Unless things get complicated.

In our example, the executives should have realized that if a rookie negotiator gets good results, it is likely that the firm is in a stronger bargaining position than initially assumed. The results were good, but they might have been better if an experienced negotiator had been in charge. Sending Bart again might be a mistake.

There are many other examples in which reinforcement might lead you astray. You liked a restaurant before, so you keep going there, even though the cook has left and a better restaurant is just around the corner. You take a different route to work and save time, so you take it again, instead of asking yourself whether traffic was just better at that time, which would make your standard route even better. You mix up success and failure with the underlying causes.

Reinforcement vs. Rationality

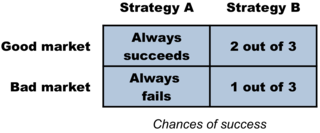

In a series of papers published in the journals Management Science, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, and Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, among others, my coauthors and I have investigated how and why reinforcement can be wrong. In our experiments, we used an abstract version of the following example (see the picture).

Suppose you have to choose between two business strategies. Their success depends on whether the market is good or bad. Strategy A will be successful for sure if the market is good, but it will fail for sure if the market is bad. Strategy B will succeed two times out of three if the market is good, and one time out of three if the market is bad. You do not know whether the market is good or bad: Let’s call the chances 50–50. But here is the key. As in the example with the negotiator, you get to decide twice (say, for two similar products). You can choose A or B, see the results, and then you can choose a second time, without the market changing.

Suppose you start with strategy B, and the first time you succeed. Great, let’s keep this strategy for the second time! On the contrary, suppose the strategy fails the first time. Panic! Let’s change to plan A!

Sounds reasonable? Sure. It’s also completely wrong.

As is often the case in business and life, the results of a decision also tell you something about the reasons behind the results. A little piece of mathematics called Bayes’ Theorem allows you to update (actualize) your beliefs: in this case, whether the market is good or bad. But we can see why a strategy of “win–stay, lose–shift” is wrong here even without doing the math.

Look at the picture again. It is more likely that B succeeds if the market is good than if the market is bad. So, if B is successful the first time, it is more likely that the market is actually good (if you do the math, the result is that the “posterior probability” of that is now 66.6 percent, not 50 percent). But then you are better off choosing strategy A, which always succeeds in a good market! Conversely, if B fails the first time, it is more likely that the market is bad. But then strategy A is a very bad idea, and you should stick with B even though it has failed. Hence, the correct way to behave in this case is “win–shift, lose–stay.” Your intuition is broken.

Well, not totally broken. If you had chosen A the first time, a success would have told you that the market was good, and a failure that the market was bad. In that case, you should stay with A in case of success and abandon it in case of failure. Reinforcement is a good way to learn in general because it is often the right thing to do, if things are easy enough. But the more complex the environment, the more likely it is that it leads you astray.

In our research, we have seen that in situations like this people very often follow reinforcement when it is wrong (around 60 percent of the time in some studies). Using response times, we have uncovered that this is because reinforcement is indeed followed intuitively: The decision does not follow deliberation, but hardwired, impulsive decision processes. And it gets worse. Using pupil dilation to measure cognitive effort and electroencephalography to measure actual brain reactions, we have shown that the problem is worse for larger incentives. For many people, if the stakes are large, winning or losing becomes more salient, and then reinforcement becomes more attractive. Instead of thinking more carefully when decisions are really important, many people follow reinforcement more. We call this the reinforcement paradox.

Lessons Learned

What do we learn? Like many processes underlying your intuition, reinforcement is a cognitive shortcut, which can pay off if you are short on time or the decision does not matter much. But, for really important decisions, you should take your time to think more carefully, no matter how convincing your gut feelings are. This is especially true when the results depend on things you do not know but whose likelihood you could gauge. Ask yourself: What does that previous success or failure tell me about the situation?

References

Achtziger, A., & Alós-Ferrer, C. (2014). Fast or Rational? A Response-Times Study of Bayesian Updating. Management Science, 60 (4), 923-938.

Achtziger, A., Alós-Ferrer, C., Hügelschäfer, S., & Steinhauser, M. (2015). Higher Incentives Can Impair Performance: Neural Evidence on Reinforcement and Rationality. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10 (11), 1477-1483.

Alós-Ferrer, C., Jaudas, A., & Ritschel, A. (2021). Effortful Bayesian Updating: A Pupil-Dilation Study. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 63 (1), 81-102.