Child Development

When Is Dying Preferable to Living?

The definition of when suffering becomes unbearable is a highly individual one.

Posted August 26, 2013

Who can say precisely when suffering becomes unbearable? This was a question I found myself asking as I worked on an article for The New York Times Magazine about the life of Brooke Hopkins, a retired English professor at the University of Utah who was paralyzed from the shoulders down in a bicycle accident in 2008. What made Brooke's case especially interesting to me is that his wife, Peggy Battin, is a philosopher who has written extensively on an individual's right to physician-assisted dying -- yet her own husband spent nearly five years, despite his profoundly diminished state, choosing to live.

Each of us no doubt has a different breaking point. For Tony Nicklinson, a British civil engineer who had a stroke in 2005 at age 51 that left him completely paralyzed except for the ability to blink and breathe, the agony and isolation of "locked-in syndrome" left him yearning for death. He needed help to end his life, though, and he and his wife argued his case for physician-assisted dying to the British High Court in 2012. Last August, after a widely-publicized trial, the court ruled against him, stating that "voluntary euthanasia is murder, however understandable the motives may be." The video of Nicklinson's helpless weeping after the verdict is agony to watch.

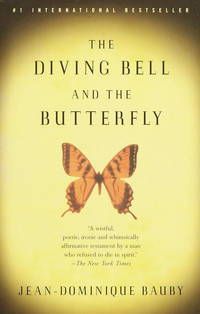

But for Jean-Dominique Bauby, a 43-year-old magazine editor from Paris who also suffered from locked-in syndrome after a stroke in 1996, that point of desperation never came. Using a tedious system of eye blinks to signify letters, much like what Brooke used with his friend Dave, Bauby dictated a short book that was a paean to the value of life even in his externally frozen state. With an active mind "there is so much to do," he wrote in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. "You can wander off in space or in time . . . visit the woman you love, slide down beside her and stroke her still sleeping face. You can build castles in Spain, steal the Golden Fleece, discover Atlantis, realize your childhood dreams and adult ambitions."

Brooke Hopkins probably fell somewhere in between these extremes. Before the collision he'd been a man of boundless gusto. "At parties he was the one who ate the most, drank the most, talked the loudest, danced the longest," one friend recalled. A striking six-foot-five, he had a winning smile and a mess of steely gray hair, and was often off on some wild adventure travel with a few of his dozens of friends. He went on treks and expeditions to the Himalayas, Argentina, Chile, China, Venezuela, and more; closer to home he often cycled, hiked, or backcountry skied in the mountains around Salt Lake. He was outsized not just physically but intellectually: he had a bachelor's degree and doctorate from Harvard, and was a hugely popular English professor who taught a range of authors -- Shakespeare, Melville, Emerson, Thoreau -- and had a special fondness for Romantic poets.

The question, then, was whether such a physical man would be able to live a life almost totally in the mind. The experience of Christopher Reeve, Hollywood's original Superman, comes to mind. Like Brooke, Christopher Reeve was outsized and handsome, fond of testing his physical limits through sailing, skiing, scuba-diving, and competitive horseback-riding, which is what led to his spinal cord injury at age 43 when he was thrown from his horse. And like Brooke, he chose life over death, seeing the challenge of recovery as a spur to working harder and harder. He managed it, living for nine years after his 1995 injury, returning to acting and directing, writing two memoirs, and testifying before Congress dozens of times to promote research into stem cell therapy. Maybe Brooke would manage it, too.

Teaching was what motivated Brooke to stay alive. From the time he moved back home after his accident -- after two years living in institutions -- he started teaching through the University of Utah adult education program. The students came to Brooke, gathering once a week in his house on M Street in a funky Salt Lake City neighborhood known as The Avenues.

The first class he taught, in the fall 2010 semester, was on Thoreau's Walden, and since then he has taught Shakespeare's "The Winter's Tale," The Iliad, The Odyssey, Dante's Inferno, Moby-Dick. One of the reasons that life finally became unbearable for Brooke was that he realized he no longer had the physical stamina or the intellectual rigor needed to teach. That is how he lost one of his most important reasons for living, and how he began turning his thoughts toward death.