Loneliness

A Mind of One’s Own?

Eros, free will, and the loneliness of consciousness

Posted January 21, 2016

The psychologist Julian Jaynes once made the strange proposition that our ancestors did not become conscious until the sophisticated literacies of the late Antique period. Today, we will ask whether we were ever conscious, or if we can be said to be conscious at all. Talking about Love will shed light on this question.

Introduction: the stripped, humiliated Self.

For today's long read in the Self & Consciousness Series, I want to ask more fine-grained questions about intentionality, agency, and the Unconscious before – or by way of – examining Julian Jayne’s provocative theory of the origins of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind.

The basic question I wish to pose is simple: are we conscious at all?

First, we need return to the naïve proposition of there existing a “true” Self that can at once hide, find, express, not express, like, dislike, deceive, control, or surprise it-self. Here, we return to our introductory questions. If I decide that I don’t like myself, what is the ‘i’ that dislikes the Self? (see my earlier post)

After posing the problem in a new light, we will focus on the last point on today’s list. What does it mean, what does it entail, for the Self to surprise itself or to happen to itself?

I should begin with an insight on the loneliness of consciousness. Or rather, with a story of how the insight presented itself to me through a fortuitous experience – a humiliating experience, as it happens.

Yesterday, I found myself spending close to five hours in a windowless room, oblivious to what lied beyond its white walls, not knowing when and how I would leave or what would happen next from moment to moment. In the most literal sense, I felt stripped of all human dignity. I was wrapped in a blue gown that at once exposed the grotesquery of my half-naked body, and concealed its shameful, exposed backside from my own eyes.

This was a terrible burden. Imagine being at once exposed to an invisible, anonymous audience that could return at any point, and made to be aware, but ever so slightly, of your own shriveled fragility – but one which (recall) you cannot, yourself, see.

I was lost, stranded, forgotten (or so it appeared) in one of the examination rooms of Montreal’s newest Super-Hospital – a structure so vast and labyrinthine that it is incomprehensible even from the outside. A doctor had briefly appeared and left, promising to return. Hours had gone by. In the most literal sense, I did not know where I was. The inner workings of the hospital factory, its winding hallways, the nature and direction of its patterns of movement were irrevocably unknowable to me.

Time passed. I meditated, read, tried to meditate again, wrote down some of my racing thoughts, then read again. Re-reading (more or less simultaneously) an essay on the Bicameral Mind thesis, and another one on Hominid enculturation and the evolution of cognition to prepare a lecture, I felt strangely focused and calm. Soon, I began to rationalize that my situation was showing me something crucial about the opaque workings of mind and brain, and the sociocultural matrix from which they continually spring.

Why did I feel so stripped of my humanity? Surely, only a minor shift in covered-to-exposed skin/clothes ratio had occurred – albeit one which I had not intended. Only one thin layer of culturally enriched encoding had vanished, and I no longer felt like myself? Yet, only the most outward visible signs of one of my performative, professional selves had disappeared.

My mind soon wandered to other realms of social ontology exposed by my solitary prisoner’s dilemma. How kafakaesque, I thought; how very typical of the alienation, anomie, rationalization, dehumanization, and loneliness of the industrial mess our species has buried itself in.

Then it struck me, re-reading a passage by Julian Jaynes, that my dilemma might expose something much deeper about the very structure of consciousness; something much more perverse than a vulgar industrial conspiracy, or the sad image of a Cartesian ego trapped in a bag of skin (as Allan Watts often put it); something central, I soliloquized, to the loneliness of the conscious experience.

So here we go. Let’s explore that insight, by way of Jayne's strange thesis.

The Bicameral Mind Hypothesis.

In Julian Jayne’s controversial thesis, humans are posited not to have evolved a “consciousness” until a very late moment in history –until as late, perhaps, as 1400-600 BCE. By Jaynes’ account (and on his reading of the Iliad in particular) our fully enculturated, linguistically competent, technologically sophisticated ancestors from the early Antique period lacked agency in a very deep sense –one much deeper than simply attributing the course of their lives to the whims of jealous Gods. Humans, or so Jayne claimed, lacked a unity of consciousness proper, and did not possess any kind of inner voice that they could identify as their own.

Our ancestor’s mental life (so Jaynes’ story goes) lacked anything we might recognize as coherent mental states or propositional attitudes. Transient streams of inner-narrations would arise in mental life, but our ancestors (so goes the claim) would experience the inner-voice as auditory hallucinations, which they would attribute to the Gods – thereby entirely lacking a notion of volition and agency.

Jayne’s thesis, by most accounts, is preposterous – grotesque even; not least for its un-verifiability. How could we possibly go about investigating what was in the heads of our ancestors and extrapolate a consensus on how they made sense of it? Are we not faced, in our daily lives, with the Problem of Other Minds? Do we not have, at best, the flimsiest anecdotal evidence for whatever other people imperfectly report from the complexity of their inner-states? Do we know enough – anything at all? – about what might constitute an ordinary state of consciousness for most people? What happens, for example, and what do people think about when their minds wander? Do we know enough about individual and cultural differences in inner-narration? (see Strawson, Bloch; Veissière, for a discussion on how little we know).

Let’s leave these questions aside for now and briefly consider Jayne’s argument.

To flesh out his Bicameral Mind thesis, He begins with a neurological story.

A tiny something (he conjectures) might have been missing in our ancestor’s brains; some pathways not yet etched; problems of functional connectivity; missing circuitry between the two cerebral hemisphere. We do know, after all, that severing the corpus callosum to reduce the incidence of seizures in epileptic patients can effectively produce split-brained persons with two separate spheres of consciousness (see Parfit for a philosophical discussion).

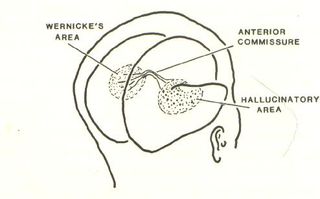

In Jayne’s Bicameral Mind, the primary actor is the right-hemisphere, effectively relegating “consciousness” to the role of spectator, with the right middle-temporal gyrus generating voices experienced as auditory hallucinations. The left hemisphere, which hosts Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas (thought to regulate language), lacks the proper connectivity with the right one to integrate these experiences as full-fledged self-generated intentional states.

So far so good?

Probably not. Even the most optimistic proponents of neuroscience agree that anyone trafficking in exhaustive neural explanations of consciousness is venturing past their pay-grade (but see Cavanna et al for what contemporary neurology has to say about bicameralism).

Jayne’s purported historical evidence (his reading of Greek myth and the Iliad) might be equally problematic. At its simplest, the argument goes that the characters of Greek myths all appear to be entirely lacking in self-monitoring, intentions, and volition; the most cited example being that of Achilles’s anger against Agamemnon, precipitated by the “vision” of Athena.

As we search for a minimalist version of this problem, we might discard the neural and historical hypotheses as too distant to be verifiable. But we will retain Jayne’s insistence that “consciousness”, whatever it is, plays an insignificant role in mental life, and is not necessary for sensory perception (see also Cavanna et al)

Does the Self happen to itself?

In order to return to my proposition that the Self is a process that happens to itself, let’s focus on this notion that consciousness only plays a minor part in mental and phenomenal activity. Another way to phrase the problem, is that, as the psychologist Merlin Donald put it, most operations of the mind and brain operate outside of consciousness. Donald illustrates this problem with an example from human speech:

“speakers blithely produce sentences at output rates that are near the physiological limits of the system without any awareness of where the words or sentences are coming from. In a sense, speakers find out what they have said when everyone else does; just prior to speaking a word or sentence in a normal conversational context, there is no awareness of precisely what is about to be said” (Merlin Donald, Hominid Enculturation and Cognitive Evolution)

In this model, it is as though speech is a phenomenon that happens to one – that is done not by the Self, but to the Self – (by whom?) as indeed we sometimes blurt out phrases that immediately embarrass our Selves – pun very much intended.

In both Jaynes’ and Merlin’s explanations, the operations of the mind and brain are shown to lie almost entirely outside conscious thought. This is an old insight. Consciousness and Cognition, like the Christian God, move in mysterious way.

Both authors are working from a [William] Jamesian definition of i-consciousness: the ‘i’ as that which, at any given point is “conscious” in the sense that it can retrieve and inspect experiences for monitoring, reflection, projection, etc. That ability for conscious retrieval, for Jaynes, is what is argued to be missing in our pre-literate ancestors. For Donald, it is precisely this evolved capacity for conscious memory retrieval and the rise of explicit memory systems, currently assumed to be missing in our Great Ape cousins, that enabled the hominid transition into cumulative cultural niches. On Donald’s view, this transition occurred much earlier than Jayne’s hypothesis. Conscious memory retrieval would have evolved slowly from rudimentary form of shared “mimetic” cultural repertoires among our tool-making Homo Erectus ancestors, up from 4 to 0.4 million years ago. This ability (Jaynes notwithstanding) is now generally agreed to have been fully present by 0.4million years ago with the rise of so-called oral-mythic culture among early members of the homo sapiens species.

At this point, I propose to turn our critique of Jaynes’s thesis on its head.

Could we argue that the claim is not so much too bold, but not bold enough? Let’s ask the question very plainly:

Are we conscious at all?

The asymmetry of consciousness and experience.

How conscious are we, I ask, when what we experience as consciousness presents itself from moment to moment in asymmetrical waves with what arises in experience from moment to moment?

We need to unpack this: the question here is how to make sense of the contradictions between the bursts of mental life that arise from experience (like the proverbial Proust remembering things past from tasting a madeleine), and the bursts of experience that arise from waves of mental life (the racing thoughts, blurted phrases, waves of emotions that all of a sudden feel like something and trigger modes of affect and courses of action). What to make of the spontaneity of the latter, against the arbitrariness of the former? Or the other way around.

This is the problem we might term the asymmetry of consciousness and experience.

Surprise and varieties of salience

So where and what is the Self in these processes? How does it reveal itself to itself and surprise itself?

A basic phenomenological take on surprise would speak of varieties of salience, and might run something like this:

Our conscious relationship with the world around us, as Heidegger viewed it, was one of zuhandenheit – or readiness-to-hand. Readiness-to-hand is the most ordinary mode of consciousness, which occurs when one is immersed in an activity or another. One is not, strictly speaking, aware of the clothes covering one’s skin, or the ground beneath one’s feat, or the legs supporting one’s trunk. But should one’s clothes tear up and bring forth the wind or cold on our skin, or should the ground begin to shake, or the knee begin to ache, then what was previously ready-to-hand becomes present-at-hand – or vorhandenheit. When a salience, or presence-at-hand occurs, we are knocked out of autopilot, and we become surprised.

Fransisco Varela was fond of explaining the phenomenology of Self-Consciousness in those terms. When the Self, for some reason or other, is brought forth to consciousness, we become self-conscious. We feel awkward, often tongue-tied, in the naked presence of our Self.

From an anthropological perspective, I am inclined to think of the Selves that are brought forth to awkward consciousness as pertaining to a shallow, social and performative kind. I may become aware of the imposture of my Professor Self during a lecture, and lose my confidence, train of thought, and stream of speech. The presence of my aunt in the audience may bring forth my eight-year-old nephew Self (my aunt obviously does not see my Professor Self), and I may become tongue-tied again.

What I want to suggest, once more, is much more perverse. I want to suggest that what continually reveals itself to the Self from moment to moment is not so much itself, or varieties of itself, but something else altogether that points to a near total absence of volitional possibilities in this dark expanse we call consciousness. I want to suggest something along the lines of involuntary hallucinations, or the whims of jealous Greek Gods. I want us to consider, very seriously, the unconscious texture of the Self.

Varieties of impotence: Moods and intentionality.

In considering this question, returning to a basic psychoanalytic notions of the Unconscious will be helpful. But before that, we should recall the generations of phenomenologists, who, after Brentano, have agonized over the intentional character of moods and emotions (see Colombetti, for a good discussion).

For most phenomenologists, the aboutness part of intentionality is not that simple. Intentionality may be objet-directed, or open. What kinds of intentional objects can emotions and moods be argued to possess, or refer to? What are they about?

Emotions are simple enough.

I am happy to see you.

She is terrified of the butterfly.

But moods (like anxiety, ennui, depression), longer lasting in character, are much more complex. They can arise without being about anything that the character (or author, in other accounts) of the mood can consciously identify and inspect.

Here is a simple scenario. All is well in bodily health, social life and play -- all of a sudden you are overcome with sadness. Or another one: you might, say, finally get to spend alone time with someone who has romantically preoccupied you for a long time, and now, in your would-be lover’s company, your anticipated emotional arousal has turned into an unexplainable feeling of void. You are tongue-tied, and want to be alone. You become irritable. You do not rationally, volitionally want to be alone. You want to want to be freshly disposed, at your most ideal social and personal performance for and with your would-be lover, and yet, something somewhere, another you will not let you. That other you seems to be in control of most of your body, and in whatever conscious effort you can summon to mentally will the other you away, you are not successful.

Which of these yous are you?

The Freudian notion of an id-driven, superego-crushed, fragile ego that can, through the conversion process of psychoanalysis, discover the true subliminal motives behind her emotions has gone out of fashion. Perhaps rightly so. So too, in most, but not in all cases, have the jealous, whimsical Gods who toy with our mortal flimsiness. In the current state of scientific and folk scientific understanding of the Mind and the Person, we have replaced the Gods and the Id with genes, hormones, and neurotransmitters. Where Zeus or Neptune were once to blame, we now have serotonin, norepinephrine, etc., etc. (see Gold & Olin for a discussion of neuropharmacology and the Self). We sometime speak of another abstraction we call “culture”, but not very much; or not very well.

A minimal story of Unconsciousness

For the purpose of this discussion, I propose that we remain agnostic about the true causes (Gods, genes, or otherwise) of moods, emotions, and most of what we spontaneously do and think, above and below the Jamesian conscious-i. Let us simply note the asymmetry of consciousness and experience, and consider how, on both sides of that asymmetry (the chance-operation of an experience giving rise to a mental state, or the other way around), the givenness of first personal experience simply happens to us. I want to suggest once more that The Self continually surprises its Self.

Eros: Opacity and Volition in the Romantic-Erotic Spectrum

What better example than Love and Sex, the very linchpins of human sociality in a literal sense, to make sense of the issue?

It is after all through sex and regimes of attraction (if not always love, and not always two-sided) that each and every human alive today and all that came before us found themselves alive.

The putative cultural and historical particularities of romantic love and its current domestic-economic arrangements, punitive and otherwise (sometime known as the Romantic Love Thesis – see Reddy) are beyond the scope of our discussion today (but see Kipnis for a funny, cynical take on the matter). Let us simplify the problem by grouping a broad range of human emotions, practices and rituals surrounding romantic and sexual attraction into a broad spectrum.

We might call this the romantic-erotic spectrum.

What invariably arises in consciousness and experience in this spectrum, I want to argue, possesses agentive qualities that do not originate in anything we might recognize as “our Self”. In other words, “we are just attracted” to some people, and not others. We cannot be volitionally attracted to anyone, and we cannot volitionally cease to be attracted to someone we may have rationally decided is not an ideal fit.

Once again, we can begin with a thin membrane of social ontology – the kind that is so easily stripped with a mere hospital gown. Cautious introspection and minimal training in the humanities may reveal, for example, that our romantico-erotic compulsions are bound to an ideal type. One in which such historically and socially specific cues as phenotype, forms of dress, manners of speech, and other socioeconomic stupidities condition who we can and cannot be attracted to.

Trying to escape the ontological idiocy and ethical violence of such 'types' will promptly precipitate one into a rabbit hole of deeper problems in the very structure of consciousness.

Sure, the notion that, say, all brunettes or men in fitted suits come prepackaged with the very same intrinsic qualities ready to be (depending on one’s honesty vis-à-vis one’s impulses) plucked, consumed, utilized, or morpheable with one’s own intrinsic-ness is readily seen as logically inconsistent and morally dubious at best. But what of the difficulty – the impossibility, perhaps? – of unlearning these ways of desiring Others? Not as easily done, certainly, as removing a hospital gown. In fact, the solution might be exactly the opposite. Unlearning ideal-type attractions may be as, or more, difficult as learning to go to work naked under an unbuttoned hospital gown. Good luck with that one.

But there is yet a deeper, or simpler problem. Love may also bring forth an antidote to the idiotic automaticity of socially-prescribed tastes and modes of affect – one which, however, still points to our volitional impotence in the face of what we feel in our deepest core.

Most of us, I suspect, have at some point or other fallen for someone we would be too embarrassed to bring to a family dinner or a workplace party. This is a good example of ontological and ethical violence. A basic violation of semiotic categories; the “wrong” styles of dress, forms of speech, hobbies and interests , etc. The social script that defines the attraction as a category mistake is readily apparent in its stupidity in such scenarios. And yet, as the social script catches up with one and makes the arrangement unmanageable, the feelings of attraction do not go away. They arose when they arose, and will go away when they go away. They are immune to the conscious will.

The problem also exists in reverse. Imagine wanting to want someone you feel morally compelled to want, but "physically" do not. You cannot do it.

How strange then, how cruel even, to have been endowed with a very physiology of attraction that can only rise or dry up through the whims of an unconscious will.

Investigating the epistemological problem of Love, I insist, doesn’t only point to (a) the opacity of Other Minds but also (b) the opacity of one’s own mind.

(a) The Other Minds Problem in Love (to illustrate) usually goes like this:

P and Q are lovers, and have shared a bed for ten years. They lie awake at night next to one another, worrying that they do not know each other at all.

P wonders: “how do I know whether she really loves me, or loves me for me, or intends the same outcome as my own in this arrangement?”

(b) The Opacity of One’s Own Mind in Love Problem goes like this:

Q wonders: “how do I know why I desire him? Why can’t I stop, or why can’t I love him again if I have stopped?”

A further take on the (a)+(b) problem in Love, finally would go like this:

One may worry that the alleged other-directed intentionality in love and attraction is not really about the Other, but is always about the Self - about the Self's way of mentally soothing itself with its idea of the Other; one of the perverse ways, some might say, in which consciousness is invariably directed beyond itself, but always re-directs the world back onto itself.

The moral implications of this question are not at stakes in today’s discussion. I simply wish to point to the Opacity in which the Self-Other spectrum, and the Self-Self spectrum are both cast. Indeed, we may simply not know enough about the Self to worry that Love is too much about one, but not two ore more Selves. Indeed, Love may simply be about itself, and no conscious Self at all!

Thus, we may conclude today’s discussion with yet another iceberg analogy.

We may have seen that William James’ conscious ‘i’, in its obliviousness to the workings of the matrices from which it springs, may be smaller than we thought.

Or we might conclude with a more pathetic image. One in which the flimsy, shriveled ‘i’, stripped of cultural meaning and dignity, stands atop a perpetually sinking iceberg that it attempts to lift in vain: like trying to lift the ground beneath your own feet; attempting to lift the entire planet on which you stand as it hurls you across the universe with unimaginable speed.

It was yesterday, then, in my Kafkaesque hospital room, that I had my melodramatic insight on the inexorable loneliness of consciousness. It was also then that I finally understood a passage from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. A passage that sometimes springs forth to my thinking voice from the vagaries of a will that is not my own:

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I.

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1834)