Psychedelics

The Magic Behind the Molecules: Psilocybin vs. Alcohol

Learn surprising facts about psilocybin, the main ingredient in magic mushrooms.

Updated December 16, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- People often assume psychedelics are more dangerous than alcohol because psychedelics are illegal.

- Alcohol and psilocybin have different effects on the brain and produce different experiences.

- Psilocybin is generally considered non-addictive and has a low risk of overdose.

Because psychedelic substances are generally illegal, many assume they are quite dangerous. As a result, people often make inaccurate comparisons between psychedelics and substances that are truly harmful, such as heroin, cocaine, or even alcohol. In reality, these are all very different substances.

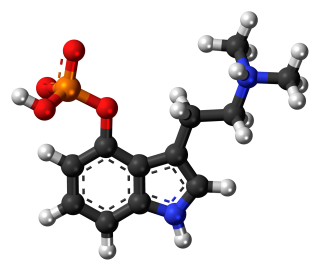

Here we compare alcohol to psilocybin – the psychoactive chemical in magic mushrooms. Although these are both substances that cause alterations in consciousness, they have distinct differences in their chemical structure, effects on the brain, and overall impact on health and well-being. Let’s take a look and compare them head-to-head.

Alcohol and Psilocybin: The Science of Spirits and Magic Mushrooms

Chemical Source

- Alcohol (ethanol) is produced through the fermentation of sugars by yeast. It is found in beverages like beer, wine, and spirits.

- Psilocybin is a naturally occurring compound produced by more than 200 species of mushrooms. These mushrooms are found in many parts of the world, including the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia.

Effects on the Brain

- Alcohol primarily affects the central nervous system by enhancing the effects of the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid). As a depressant, it slows down brain function and neural activity.

- Psilocybin is a more complex molecule that works by affecting the serotonin receptors in the brain, particularly the 5-HT2A receptor. It can cause changes in perception, mood, and thought, often referred to as a psychedelic or hallucinogenic experience.

Physical and Psychological Effects

- Alcohol can cause decreased inhibition, impaired judgment, poor motor coordination, and at higher doses, it can cause drowsiness, respiratory depression, or even coma.

- Psilocybin can cause visual and auditory hallucinations, poor motor coordination, an altered sense of time, spiritual experiences, and introspection. The effects can be euphoric or frightening, varying greatly depending on the dose and individual.

Health Risks

- Alcohol has a risk of addiction and can cause serious health problems, including liver disease, cardiovascular issues, and permanent damage to the brain. Withdrawal from alcohol can be dangerous and also involve damage to the brain.

- Psilocybin is generally considered non-addictive and has a low risk of overdose. However, it can cause psychological distress, especially in those with a history of trauma or psychosis. Medical problems from psilocybin use are rare.

Legal Status

- Alcohol is legal in most parts of the world for adults. It is considered an important part of social, cultural, or religious practices in a majority of cultures and countries around the world.

- Psilocybin is illegal in the United States, Canada, and many other countries, though there is a growing movement to re-evaluate its legal status, particularly for mental health.

No Comparison

While both substances alter consciousness and can affect mood and perception, they do so through very different mechanisms and carry different risks, experiential effects, and legal statuses. Although alcohol is culturally ingrained in many social contexts, its high potential for abuse and significant health risks overshadow its limited therapeutic uses. Notably, it is prohibited or discouraged in certain social, religious, and cultural groups for this reason. Conversely, psilocybin mushrooms have been used by traditional healers in Central and South America for centuries.

Despite its current legal restrictions, psilocybin is also showing potential in clinical research for treating various mental health disorders. Therefore, from a health and therapeutic perspective, psilocybin may be of greater societal value than alcohol, especially considering the emergent interest in its applications for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and end-of-life distress. Although there is wider social acceptance of alcohol, it poses greater risks to individuals and public health. The magic from the mushroom, ironically, may help address this very issue, as some of the most promising new psychiatric research advances psilocybin as a viable treatment for alcohol use disorder.

References

Bogenschutz, M. P., Ross, S., Bhatt, S., Baron, T., Forcehimes, A. A., Laska, E., ... & Worth, L. (2022). Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(10), 953-962.

Nutt, D. J., King, L. A., & Nichols, D. E. (2013). Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(8), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3530

Sloshower, J., Guss, J., Krause, R., Wallace, R., Williams, M., Reed, S., & Skinta, M. (2020). Psilocybin-assisted therapy of major depressive disorder using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a therapeutic frame. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 12-19.

Ross, S., Bossis, A., Guss, J., Agin-Liebes, G., Malone, T., Cohen, B., Mennenga, S. E., Belser, A., Kalliontzi, K., Babb, J., Su, Z., Corby, P., & Schmidt, B. L. (2016). Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30 (12), 1165–1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116675512