Suicide

Is New Federal Law Encouraging Cops to Commit Suicide?

The hidden danger behind well-intentioned efforts to support law enforcement.

Posted August 23, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- In August 2022, two bills were signed into law by President Biden to support traumatized law enforcement officers (LEOs) and their families.

- Providing benefits to the surviving families of LEOs who killed themselves could unintentionally incentivize other officers to take their lives.

- Psychologists have identified several potential causes of police suicide, but one common thread is the inability to seek or find help.

On August 16th, President Biden signed two bills into law, the “Traumatic Brain Injury and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Law Enforcement Training Act” (H.R. 2992) and the “Public Safety Officer Support Act of 2022” (H.R. 6943). There is much to be appreciated in both bills and a hidden danger in one of them.

Why are these bills important?

Police officers and other first responders see more tragic, cruel, and traumatic events in the first few years of their careers than most people will see in a lifetime. These bills go a long way to reduce stigma and develop effective means to support traumatized officers and their families.

Families of officers who have committed suicide have long lobbied for recognition that work-related trauma is a major contributor, if not the cause, of their loved one’s death. Officers who die in the line of duty are routinely honored for their courage and dedication. Officers who kill themselves are more often shrouded in shame, their families left stranded emotionally and financially.

The Public Safety Officer Support bill (H.R. 6943) attempts to right this wrong by allowing families of public safety officers who die by suicide linked to work-related traumatic circumstances to apply for death benefits. A driver of this new legislation is Erin Smith, whose husband, Metropolitan police officer, Jeffrey Smith, killed himself nine days after he was injured in the January 6th attack on the Capitol.

Cops and suicide

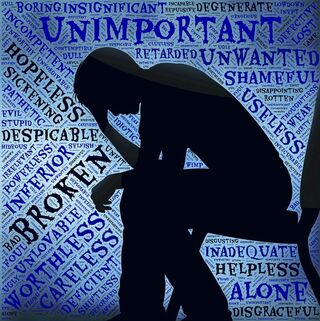

For years, police and mental health professionals have tried to reconstruct events that lead to suicide. Their psychological autopsies implicate alcoholism, family conflicts, relationship losses, disciplinary problems, depression, posttraumatic stress, immediate access to guns and skill in using them, drug abuse, sleep problems, poor coping skills, financial difficulties, age and gender, job stress, exposure to work-related trauma, scandal, shame, failure, betrayal, and a distorted but culturally correct sense of invincibility and independence. If there is a common thread linking these elements, it is the doomed officer’s inability to ask for or find confidential help before small problems snowball into a tidal wave of torment.

An alarming statistic

What we do know now is that cops are two to three times more likely to kill themselves than they are to be killed in the line of duty. This is alarming given that most police officers were once hardy enough to pass a demanding application process, a rigorous psychological screening, and an arduous training program.

The hidden danger of the public safety officer support bill

Some of my colleagues and I are concerned that this bill creates an incentive for law enforcement officers (LEOs) to take their own lives. Depression is highly correlated with suicide. People who are depressed tend to think with a logic clouded by hopelessness. They cannot see a way past their troubles. Suicide seems like their best and only option. They believe their family and their friends would be better off without them. With the passage of this bill and the potential for death benefits to the surviving family, LEOs may be falsely supported in thinking that suicide is the right thing to do because it will leave their families in financial good shape.

A message to officers

Straight talk to the officer who thinks that killing themselves is okay because now your family will have benefits: Don’t do it. Killing yourself will screw up your family, perhaps for generations to come. Suicide is not a victimless crime. Your death will damage everyone you know, especially your family and your children. People who survive your death will be overwhelmed by questions tinged with self-blame: If only I’d been a better wife, a better husband, a better partner, gotten better grades in school, listened more, not left the house.

My colleagues and I have sat with grieving family members and co-workers. We watched as they blamed themselves or each other for your death, tearing the family you think you are helping to shreds.

Instead of helping your family with your death, you are sending them into a world where they may be shunned by others or isolate themselves out of shame or awkwardness.

Your death will be especially damaging to your children. Kids whose parents commit suicide are almost twice as likely to kill themselves as those whose parents are still alive. That number increases to three times as likely if their parent’s suicide happened when they were younger than 18.

Money is not the answer: The answer is reaching out for help. If you are contemplating ending your life or know someone who is, get help. Tell a friend. Be brave enough to admit you are circling the drain. Give your weapons to someone else to hold for you. Stop drinking. Find a culturally competent professional who understands what you do, why you do it, and the culture your work in. Don’t wait until a pile of problems becomes a tidal wave.

If you are hurting, for whatever reason, you deserve help. Don’t compare yourself to others or to their experiences. Getting help doesn’t mean you are weak or that you are an imposter. It means you are human. Quit trying to be perfect. It’s a trap. So is giving in to stigma. Nobody’s perfect. Stop isolating yourself out of embarrassment, fear of burdening others, or concern that no one will understand or can relate to what you’re going through. Get over thinking your death will right a wrong or change anybody else. That’s the equivalent of drinking poison and expecting the other person to die. Hang in there. Without life there is nothing. With help, there is hope.

Peer-staffed resources

The following are resources where you can talk to another first responder. Use them, please. Pick up that 1,000-pound phone.

- Safe Call Now (206)-459-3020 is a nationwide, confidential, comprehensive, 24-hour crisis referral service for public safety employees, emergency services personnel, and their family members.

- COPLINE 1-800-267-5463. 1-800-COPLINE is a 24/7 confidential hotline dedicated to serving active and retired law enforcement officers and their loved ones.

- The First Responder Support Network offers retreats for LEOs suffering from traumatic stress and their families. I have been volunteering here for 15 years. Watch the video. Check out the retreats. Pick up the phone.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7 dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Children Who Lose a Parent to Suicide More Likely to Die the Same Way: Retrieved from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/children_who_lose_a…

Kirschman, E. (2018) I Love a Cop: What Police Families Need to Know-3rd edition, New York. Guilford Press.