Memory

Time Flies When You’re Having Fun

New article reveals that speech actually sounds fast when you’re distracted.

Posted January 12, 2017

Ever had trouble keeping up with a conversation while you’re driving a car? A new article published in the Journal of Memory and Language may help explain why that’s the case.

Speech scientists have often investigated the production and perception of speech in ‘ideal circumstances’; that is, in noise-free listening booths without any form of distraction from the experimental task. However, as we all know, actual conversations take place in a wide range of environments, ranging from a bar with loud background noise to situations where you’re distracted due to multitasking demands (e.g., listening while driving or searching a menu).

From our own experience we know that following a conversation accurately while performing another task can be quite difficult. Why that is the case remains a topic of debate amongst speech scientists. The new study adds to this debate by showing that speech actually sounds much faster when you’re distracted by having to perform another task.

First, it’s important to know that fast speech (e.g., a sentence like “Now listen to the word…” produced at a high speech rate) can actually change your perception of following words. For instance, consider a sound that is ambiguous, something between a short b sound and a longer w sound. If you hear this ambiguous sound embedded in a word like “bear” preceded by the rather fast sentence quoted above, suddenly the word sounds like “wear”! That is, relative to the short sounds in a quickly spoken sentence (vowels and consonants with relatively short durations), the ambiguous b/w sound stands out as relatively long, meaning that most listeners will report hearing “wear” instead of “bear” (and vice versa for slow contexts).

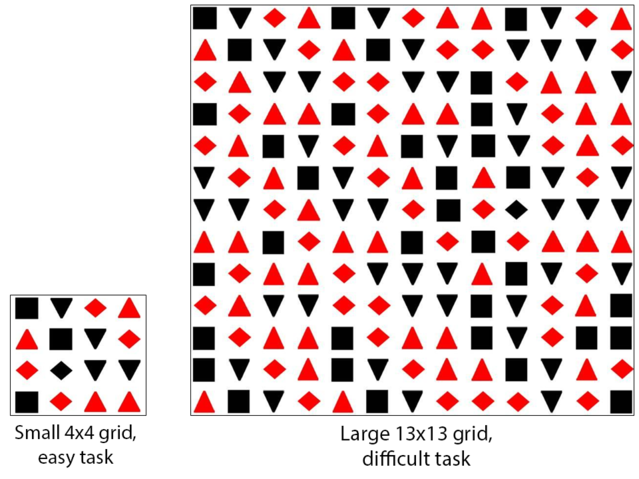

Now, in the new paper, the authors presented participants with similar kinds of materials: fast and slow context sentences, followed by these ambiguous target words. Participants were instructed to indicate what the last word in the sentence was. That was not their only task, though. Participants also received a second task, namely to search for an oddball object (a black diamond; can you find it in the grids below?) in a grid of similar looking objects (see below). Sometimes these grids were rather small, making the search task easy, but at other times the grids were rather large, making the search task much more difficult. Moreover, participants saw the visual grids only for a very short time, adding to the difficulty of the task.

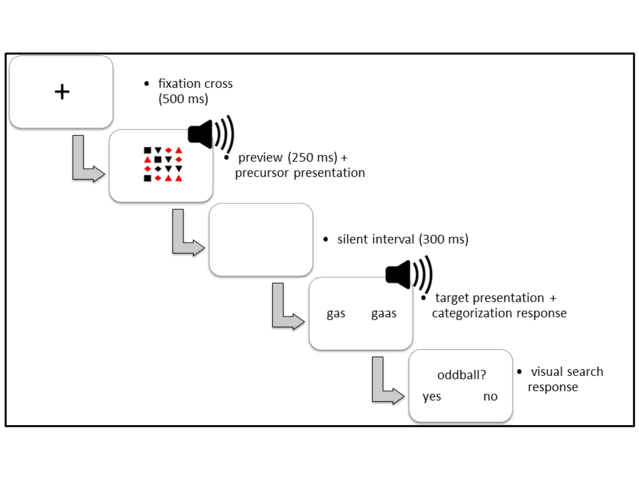

Crucially, participants had to perform both the listening task and the visual search task at the same time! So while they were listening to the context sentence (e.g., “Now listen to the word…”), they were distracted from listening by having to simultaneously search for an oddball in the visual grids (see trial structure below).

Interestingly, participants reported hearing many more w words than b words (in the paper, words with long vowel /a:/ vs. short vowel /ɑ/ in Dutch) when they had to search the larger grids. That is, when they were seriously distracted from the speech by having to perform a difficult task, they reported more w words as if the speech they had listened to was produced at a fast rate. This suggests that when participants experienced more difficulty with the visual search task, the speech they heard during that difficulty sounded faster, biasing their perception of subsequent target words towards “wear” instead of “bear”. So even though the speech was not actually fast, it was perceived as faster due to the dual search task, changing perception of the following target words.

All in all, the paper suggests that the phrase “Time flies when you’re having fun” also applies to speech perception. Speech actually sounds faster when you're distracted by having to perform another task. So next time you’re driving a car and you find that you’re having trouble following what your friend next to you is saying, ask him to slow down!

References

Bosker, H. R., Reinisch, E., & Sjerps, M. J. (2017). Cognitive load makes speech sound fast, but does not modulate acoustic context effects. Journal of Memory and Language 94, pp. 166–176. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2016.12.002.