Play

Puzzles: The Joy of Perplex

A.J. Jacobs on puzzles as a window into the brain's trickery.

Posted May 26, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Discovering that his own name was a clue in a Saturday New York Times crossword puzzle was the most triumphant day of author A.J. Jacobs’ life. Or so he thought until he realized that the Saturday puzzles use the most difficult and obscure clues—as in “the-voice-of-the-car-in-the-sitcom-My-Mother-the-Car”* obscure.

Jacobs, the author of many books, including The Year of Living Biblically and The Know-It-All, began to perseverate as to what exactly this conveyed about his cultural relevance. Inevitably, rumination gave way to literary grist, and soon Jacobs was studying Lewis Carroll's anti-riddles (that's a riddle without a solution) and inviting Garry Kasparov to his house to play chess. (Jacobs writes that Kasparov was ok with the $15 chess set on hand–it reminded him of the USSR).

The result is The Puzzler: One Man’s Quest to Solve the Most Baffling Puzzles Ever, From Crosswords to Jigsaws to the Meaning of Life. Jacobs chatted with me about the semi-sadism of puzzles and how they taught him to “hold his hypotheses loosely.”

You write about many unsolved puzzles. If you could personally solve one, which would it be and why?

Well, of course, I’d solve the puzzles of climate change and how to save democracy. But in terms of less metaphorical puzzles, there’s a famous unsolved code called the Beale Cipher. It was created by a 19th-century prospector in Colorado and allegedly leads to a treasure worth millions. Many think it’s a hoax. But if it isn’t, solving it would be a nice combination of dopamine and cash.

Puzzles play on a set of errors in information processing. Are there any cognitive biases or ways of thinking to which you’re less susceptible?

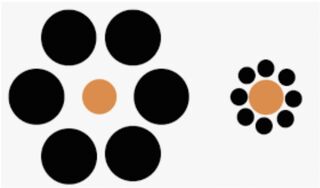

There are so many! An easily demonstrated one is the famous optical illusion called the Ebbinghaus Illusion (I explored optical illusions because they are the cousins of puzzles). Which orange circle is bigger? Well, they’re the same size.

We just think the one on the left is smaller because it’s surrounded by huge black circles. We are overly susceptible to comparison warping our perspective. And it’s a crucial bit of wisdom to keep in mind. For instance, I can be grateful that I have enough money to live a comfortable life, or I can compare myself to Bezos and other gigantic circles and stew that I’ll never get my own phallic-shaped rocket.

What are some others?

Well, there's apophenia, which is the tendency to find a signal in noise – even when there isn’t one: To see the Virgin Mary’s face in a piece of French toast or a big dipper in a collection of stars.

I call it the "dark side" of puzzles because we are wired to find patterns, and pattern-finding is incredibly important, but it can go awry. When we are overzealous and become attached to our pattern hypothesis in spite of evidence to the contrary, that’s when it’s dangerous. QAnon is an example of apophenia. They have found a non-existent pattern and cling to it.

What's a classic riddle or puzzle that everyone gets wrong?

Well, as Daniel Kahneman has taught us, be wary of your gut. It can often mislead. Here's one:

A ball and a bat cost $1.10 total.

The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

My gut wants me to answer that the ball is .10 cents, and the bat is $1. But that’s wrong. Then the total would be $1.20.

The answer is, the ball costs .05 cents, and the bat is $1.05.

Our System 1 often leads us astray.

Another lesson: Be flexible in your thinking. You can’t solve puzzles if you fall in love with your first hypothesis. Hold your hypotheses loosely, and be eager to see them disproved. I try to do this with life opinions as well as puzzles.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

Well, first, I hope they’ll have a great time reading it, and solving the puzzles, and gaining an appreciation for puzzle types they might not have known about. I also hope they’ll come away valuing curiosity more than ever. As I say in the book, “Get curious, not furious.”

And there’s a chance they can take away $10,000. No purchase necessary, by the way.

When I was a kid, I was obsessed with this book Masquerade. It came out in 1979, and it’s a series of beautiful illustrations that contained clues to the location of a buried treasure somewhere in the UK. The book created a mania. Treasure hunters dug up yards all over England. I wanted to recreate some of that excitement I felt as a kid, but without causing destruction of property. So the treasure isn’t buried. But there are clues hidden in the introduction that will lead to $10,000. The intro is available for free.

Your study of puzzles ranged from anagrams to one-of-a-kind puzzles that have never been solved. Do you think that certain personality types or professions gravitate to certain types of challenges?

There’s a stereotype that there are two types of puzzlers: Word puzzlers and math/logic puzzlers. And like dog people and cat people, you’re supposed to be one or the other. But I disagree. There are plenty of people – including me – who like them both. Plus, not every puzzle can be so reductively categorized. Where do jigsaws fit in? And Japanese puzzle boxes? The puzzle world is a wonderful and complicated spectrum. To use current lingo, I think a lot of people are Puzzle Fluid.

References

*The answer is "Ann Sothern," which A.J. Jacobs writes in the introduction to The Puzzler is a typical Saturday clue reflecting "Stuff no normal person knows."