Sex

Lust and Other Thoughtcrimes

From sins against God to sins against the PolitCorrect Bureau.

Posted March 12, 2018

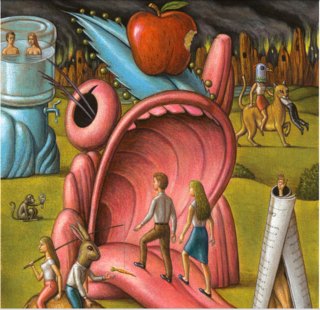

My favorite piece of art in the March issue of PT is the allegory that accompanies an essay on sexual misconduct in the workplace, (“Uncharted Territory”). Illustrator Marc Burckhardt conjures the sudden-distrust-amidst-perennial lust that increasingly typifies male/female relations. It’s Hieronymus Bosch, had the painter's hellscape been the office park rather than the Garden of Eden.

In the medieval world of Bosch and biblical fealty, thoughtcrimes were sins against God and against oneself. In our post-Orwellian era, thoughtcrimes are sins against “acceptable” social discourse. This can complicate many a subject, including sexual misconduct. In the essay illustrated by Burckhardt, Leon Seltzer considers the role of biology in men’s sexual misbehavior, as well as a male motive that’s been overlooked in the discourse about harassment. Hint: Medieval theology made a distinction between “intemperate” sinners who have no qualms or remorse, and “incontinent” sinners who are tormented by their own wrongdoing, but still capitulate to passion and lust.

The male sex drive is a contributing force in misconduct, and the sex drives of men and women differ on average, as do job preferences, interests, and aptitudes in some areas. If we create a hostile environment for information by denying facts that are scientifically established—no matter how dissonant or politically incorrect—we drive people underground and retard scientific inquiry. Frank discussion about behavioral genetics, individual differences, intelligence and sex differences has never been more fraught, and it's happening just as a cultural spotlight is trained on sexual harassment and gender ratios in various fields.

That's a shame, because societal introspection decoupled from scientific understanding is always dangerous: You end up with flawed policies that either don’t help, or that have unintended deleterious consequences. It is far too soon to say how a heightened awareness of sexual misconduct in the workplace will play out. But the growing call to place equal numbers of men and women in *all* professions, corporate boards and public panels is misguided. There are fields that women simply don't study or enter at the same rate as do men, despite all the aptitude, encouragement and support in the world. If the academy nevertheless insists that half the enrollment in all STEM-tracks at top schools must be female, what happens to the equally or better-qualified men? And why, if biological sex differences don’t exist, are people not outraged that men are wildly underrepresented in the ranks of nursing and elementary school teachers?

By almost every measure we live in a halcyon age of reason, as Steven Pinker cogently argues in Enlightenment Now. There are governmental programs that address not just standards of living but also psychological conditions that impede well-being. A minister for loneliness was just appointed in the UK, and the United Arab Emirates boasts much-touted minister of happiness. (We discuss societal interventions for loneliness in our cover story, "A Cure for Disconnection.")

It's ironic, then, that seemingly basic topics such as the professional preferences of men and women are more polarizing than ever, and that discussion of inappropriate workplace dynamics almost entirely skirts the issue of male libido.

In the face of rapid progress and change, silence about any aspect of human nature is counterproductive, if not retrograde. We’ve begun a species-wide discussion about altering humans with technologies that will someday be available at scale. Shouldn’t we first understand human nature itself, given that it is the one constant we have to work with? It is this very constancy that makes Bosch's repressed carnality resonate across time and space. "Art cannot be modern," said Egon Schiele, another artist obsessed with sex and transgression. "Art is primordially eternal."

Bosch slyly documented a handful of human urges and foibles. Five hundred years later, behavioral science can elucidate far more, and psychologists can make recommendations for the road ahead. Let’s not refuse to listen.

This article is expanded from the Editor's Note in the March print edition of Psychology Today.