Bias

Why We're So Easily Fooled, and Why It Matters

Studies of our inherent biases deliver some startling results.

Posted December 8, 2014

Guest post by Caitlin Millett

The holiday season is fast approaching, and that means gift buying. With each passing season, finding the perfect gift for loved ones seems to become more and more difficult—a phenomenon not unrelated to the seemingly exponential growth in buying options each year.

So how do we do it?

Many of us would like to believe that our decision-making is based in logic and objectivity. Studies have shown, however, that our preferences are highly biased, based on our expectations.

For decades, psychological research has supported the presence of inherent bias in human perception. A 2001 study titled The Color of Odors examined the effect of color on odor and taste perception of wines. In the experiment, wine experts were presented with two glasses of wine: one red and one white. Each was asked to describe the wine as they experienced it. The experts used words like citrus, flower, lemon, and honey to describe the white wine, whereas they used words like clove, musk and crushed red fruit to describe the red.

However, all of the experts had been unwittingly duped: both glasses actually contained the same white wine, the only difference between them being a little red food coloring in one glass. Not a single expert was even able to identify that both glasses contained white wine, and they all described the colored white wine as they would have a red. This classic study reveals the power that expectations have on how we perceive the world.

While this and other studies have revealed a lot about the underlying motives of human judgment, they rarely touch on the neuroscience behind these phenomena. A 2008 CalTech study, however, began to shed light on how preconceived notions and labels influence our thinking.

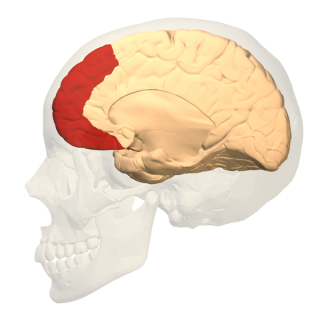

In this study, subjects were placed in a functional magnetic resonance imager (fMRI) and presented with two glasses of wine, one labeled $5 and a second labeled $90. However, the subjects were not told that the wine in each glass was actually the same $90 wine. They found that the average self-reported experienced pleasantness (EP) score was greater for the wine labeled $90 as compared to that labeled $5. More important, the higher EP score corresponded to an increased blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of the brain, meaning that this area was more active when tasting the wine labeled as more expensive. The frontal lobe of the cortex is an area of the brain important for high-level cognitive function and top-down processing. It has been shown to be essential for decision making, planning for future events, and reward comparison.

This study revealed that the mPFC did not respond to the wine, per se, but rather in accordance to whether or not it had received the better wine. An earlier Stanford study revealed that the mPFC responds when the outcome of a reward comparison is revealed and the mPFC is active only after a reward is gained. Therefore, the activation of the mPFC is not directly tied to true sensory signals or inherent quality, but to the markers and labels—signals of quality. The mPFC performs at a higher level of abstraction than brain areas that objectively sense the world around us. In fact, in studies involving the insular cortex—the area of the brain that perceives taste—no difference between the two wines was detected.

These studies demonstrate how our own brains can fool us, stemming from the fact that different parts of it process stimuli differently. Bottom-up processing is when we perceive reality objectively based on stimulus—we let the sensations guide our perceptions. Top-down processing is when we drive our own reality based on perception. The frontal cortex’s predisposition for top-down processing is one reason why the subjects in these studies were so easily tricked, and it is why we humans are predisposed to bias.

However, expectation can influence more than just our perceptions of wines—it can influence our expectations of people, too. A study conducted by Rosenthal and Jacobson established what is known as the Rosenthal Effect, which states: The greater the expectation of achievement, the greater the level of success.

The study went like this: To test whether a teacher’s expectation of student performance affected student achievement outcomes, researchers gave an IQ exam to elementary school students and ranked them based on scores. Teachers were told that the top 20% of students have high potential to succeed and were provided with the names of these students. What the teachers didn’t know was that they had actually been given a random list of names. At the end of the school year, the researchers returned and administered the exam again to the same group of students.

What they found was astonishing: The second- and third-graders who'd been labeled as “bright” at the beginning of the year had advanced significantly beyond their peers—with significantly higher IQ scores on average. The researchers concluded that the teachers’ expectations of student achievement actually became self-fulfilling. Those students labeled “smart” actually became so. The teachers, consciously or unconsciously, paid closer attention to these students, or treated them differently when they were having difficulty. The teachers and students at this elementary school believed in the existence of “smart” and “not-so-smart” students, and so they made it their reality.

This idea extends beyond labels of intelligence: Subsequent studies have shown that labels based on race, class, and gender can influence our perceptions of people just as strongly.

All that being said, does it mean you should be doing your holiday shopping with a blindfold to protect yourself from unconscious biases? Should you blindly grope through racks of wool and cashmere to find something inherently pleasing to the touch? Probably not, though it might be worth the befuddled reactions you get from sales associates. But there is something to be said for trying to minimize harmful bias.

Holiday shopping may be a small-stakes enterprise when it comes to upholding the ideals of equality and fairness in our society, but these principles will surely slip away if we are not vigilant in maintaining our awareness of these prejudices. The goal here is not to entirely eliminate prejudice—that would be a futile undertaking indeed—but to let science enlighten our culture to them.

References

Darley, J.M., Gross, P.H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33.

Eberhardt, J. L., Dasgupta, N., & Banaszynski, T. L. (2003). Believing is seeing: The effects of racial labels and implicit beliefs on face perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 360-370.

Knutson B, Fong GW, Bennett SM, Adams CM, Hommer D (2003) A region of mesial prefrontal cortex tracks monetarily rewarding outcomes: Characterization with rapid event-related fMRI. Neuroimage 18(2):263–272.

Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001). “An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function”. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 167–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1992). Pygmalion in the classroom: Expanded edition. New York: Irvington Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A., & Boroditsky, L. (2007).