International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

How Can You Be Blind if You Still Can See?

Defining blindness, low vision, and visual impairment.

Updated August 16, 2024 Reviewed by Margaret Foley

Key points

- Visual impairment occurs on a continuum, from correctable vision to low vision to total blindness.

- Most people classified as blind have some sight.

- Definitions of blindness vary around the world and over time.

When I entered third grade, I no longer could read what was written on the blackboard while sitting at my desk several rows back. I had entered the ranks of the visually impaired and was fitted for glasses.

The term “visually impaired” applies to people whose reduced vision limits their ability to perform routine activities of daily living, such as watching television (Lee et al., 2024). Visual impairment usually is treated with corrective lenses or refractive surgery. In my case, corrective lenses gave me “normal” (i.e., 20/20 to 20/30) vision for 50 years.

When I turned 60, my vision began to deteriorate rapidly as a result of a series of eye surgeries and the development of glaucoma. Within two years, I lost the ability to see even the largest letter on a standard eye chart but could still count fingers held a few feet from my eyes. I had entered the ranks of the blind.

An acquaintance wondered, “How can you be blind if you still can see?”

In everyday language, “blindness” means the inability to see anything at all. But formal definitions of blindness have long allowed for varying degrees of residual vision. For example, a report issued in 1915 by a committee of the Royal Society of Medicine defined what it called "practical blindness":

Many persons who can perceive light, and in some degree the form of objects, are yet practically blind as regards the ordinary activities of life, and it would be unreasonable to withhold from them such aid as is given to the totally blind. (Smith & Paton, 1915, p. 149)

In other words, people with residual vision should be classified as blind if their ability to function in everyday life is not much better than those with no vision at all. The reason for making this argument was (and still is) a legal one: Governmental agencies wanted to know who is eligible to receive the benefits and services available to the blind.

Determining Who Is and Who Is Not Blind

In her 2009 article “On Blindness,” disability studies scholar and Victorianist Julia Miele Rodas wrote:

[Blindness is] a continuum, or a variety, with such myriad gradations and such a jumbled diversity of seeing and not-seeing that it becomes virtually impossible to put a finger on one point and to declare, There! This person is sighted, and that one is blind. (p. 117)

Although each blind person is indeed unique, communication among researchers, clinicians, clients, and others is more understandable and less ambiguous if we can identify and measure objectively core features of vision loss.

The definition that has had the greatest influence in the United States was developed by a committee of the American Medical Association (AMA) 90 years ago. The committee “was appointed in response to a request from the Department of Public Welfare of the State of Illinois for a definition of blindness, in scientific terms, that might be made statutory" (Jackson et al., 1934. p. 1445).

This definition focuses on two core features of vision loss:

- Markedly reduced visual acuity

- Markedly reduced peripheral vision

The term “visual acuity” refers to the sharpness and clarity of vision when looking directly at an object. The AMA definition states that a person is blind if their corrected visual acuity in the better eye is 20/200 or worse.

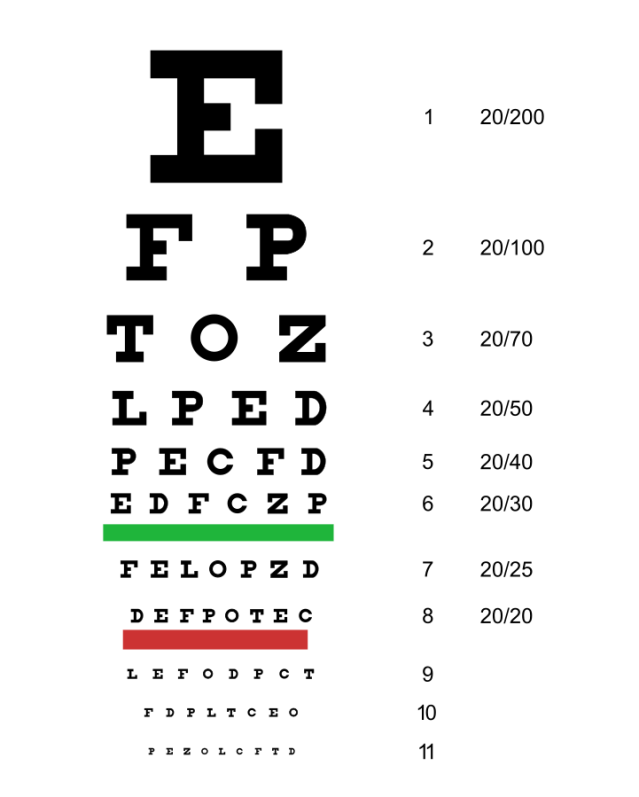

A person who is wearing corrective lenses (i.e., glasses or contact lenses) but still can read only the top line of a typical eye chart has 20/200 vision (see Figure 1). This person would need to stand 20 feet away from the eye chart to see it as clearly as a visually unimpaired person standing 200 feet away from it.

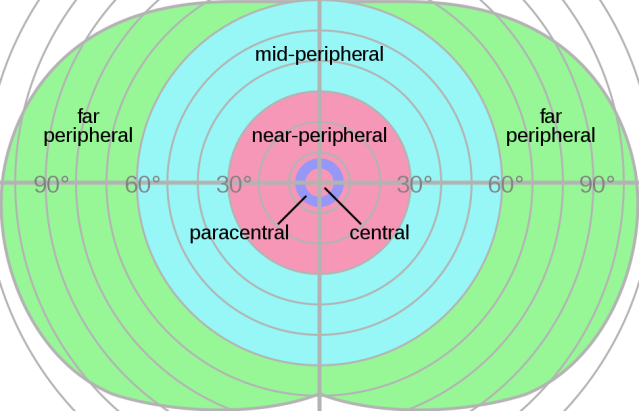

The second core feature in the AMA definition of blindness is markedly reduced peripheral vision, referred to as “visual-field deficits.” The visual field is everything you see side-to-side and up-and-down when you look directly at a single point in front of you. In visually unimpaired people, the visual field extends more than 120 degrees from left to right and about 90 degrees from top to bottom (see Figure 2).

The visual field is separated into two visual areas:

- central vision, which is the small area in the center that sees the fine details of objects (measured as visual acuity)

- peripheral vision, which is the large area surrounding the center that sees objects in much less detail

The AMA definition states that a person is blind if their entire visual field extends only 20 degrees or less around the center (Koestler, 2004). It is as if the person is looking at the world through a long tube.

The AMA definition of blindness also includes people who are “totally blind,” which means that they have no light perception. Totally blind individuals, however, make up only about 10 to 20 percent of those meeting the AMA criteria for blindness (Kleege, 2005; Lee et al., 2024). Therefore, the vast majority of legally blind people have some sight.

The AMA definition was quickly adopted by federal and state legislatures, which included its language in legislation providing benefits and services to the blind (Koestler, 2004; Lee et al., 2024). Most importantly, the U.S. Congress included the definition in the 1935 Social Security Act.

But the AMA definition arbitrarily excludes others whose vision is so impaired that it causes significant difficulties in everyday functioning (Leat et al., 1999; Vaishali & Vijayalakshmi, 2020). Today, these people are classified as having “low vision.”

Low Vision: Disabled but Not Blind

In the 1950s, Gerald Fonda and Eleanor Faye, working at the Lighthouse for the Blind in New York City, coined the term “low vision” and applied it to people with uncorrectable sight loss that did not meet the AMA criteria for blindness (Leat et al., 1999; Mogk & Goodrich, 2004). They defined “low vision” in practical, functional terms—as the significantly reduced ability to perform important activities of daily living, even with the best corrected vision. For example, a person wearing glasses who has trouble seeing a face across a room would be classified as having low vision.

Functional definitions of low vision are appealing because they take into account the specific needs of individuals as well as the daily activities most important to them. But clinical evaluations based on these definitions depend on the subjective judgments of clinicians (Leat et al., 1999).

Thus, specialists have tried to develop definitions of low vision that include numerical measures. Some definitions of low vision, for example, specify a range of visual acuities from 20/70 to better than 20/200 (Mogk & Goodrich, 2004). But clinical evaluations of low vision include other aspects of vision, such as depth perception and the ability to distinguish an object from its background. This is a complex issue that I plan to return to in a future post.

The World Health Organization: Definitions of Vision Impairment and Blindness

The World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for the development and implementation of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)—a classification system used globally. The 11th revision of the ICD, which took effect in 2022, lists several categories of vision loss that make up a continuum from mild impairment to total blindness (World Health Organization, 2022).

The ICD definition of "blindness" is stricter than the AMA definition:

- ICD: visual acuity worse than 20/400

- AMA: visual acuity worse than 20/200

- ICD: visual field extends 10 degrees or less around the center

- AMA: visual field extends 20 degrees or less around the center

This comparison shows that the answer to the question “Is this person blind?” depends on who is asking and why they want to know. The differences in the ICD definition are due, in part, to the fact that it is used primarily in epidemiological research around the world (see ICD Reference Guide).

In this blog, unless I state otherwise, I use the AMA definition to classify people as blind. In my next post, I will examine the influence of social stereotypes in the lives of people who are blind.

References

Jackson, E., Snell, A. C., & Gradle, P. S. (1934). Report of the committee on definition of blindness. Journal of the American Medical Association, 103(19), 1445-1446

Kleege, G. (2005). Blindness and visual culture: An eyewitness account. Journal of Visual Culture, 4(2), 179-190.

Koestler, F. A. (2004). The Unseen Minority: A Social History of the Blind in the United States. American Foundation for the Blind. (Original work published 1976)

Leat, S. J., Legge, G. E., & Bullimore, M. A. (1999). What is low vision? A re-evaluation of definitions. Optometry and Vision Science, 76(4), 198-211.

Lee, S.Y., Gurnani, B., & Mesfin, F. B. (2024). Blindness. StatPearls.

Mogk, L., & Goodrich, G. (2004). The history and future of low vision services in the United States. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 98(10), 585-600.

Rodas, J. M. (2009). On Blindness. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 1(2), 115-130.

Smith, P., & Paton, L. (1915). The definition of blindness. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 8(Section of Ophthalmology), 149-154.

Vaishali, K. V., & Vijayalakshmi, P. (2020). Understanding definitions of visual impairment and functional vision.Community Eye Health, 33(110), S16.

World Health Organization. (2022). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision).