Empathy

The 5 Core Skills of Hostage Negotiators

We are all involved in crisis situations; learn the skills to get out of them.

Posted October 5, 2015 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

The goal in law enforcement crisis situations where crisis and hostage negotiators are being utilized entails influencing a behavioral change in someone in order to gain voluntary compliance. Although initially this statement might sound jargon-filled, it simply means using a set of skills to get a person to stop acting the way he or she currently is and getting that person then to act the way you want them to.

The following are the core skills taught in initial law enforcement crisis and hostage negotiation courses across the world. Although you as the reader most likely will never be negotiating with someone threatening suicide on the ledge of a bridge or claiming if their demands are not met they will take someone’s life, you deal with your own crisis situations daily. This ranges from decision-making strategies at work, giving directives to employees, making a sales pitch, negotiating terms of a contract (a house for example), and determining financial and budget plans.

The unifying factor is in crisis situations a person’s actions are being dictated by their emotions at the detriment of rational thinking. Therefore, an effective crisis negotiator seeks to reduce the negative emotions that are dictating the person’s actions and bring back a more rational thinking process by employing the skills below.

The skills are active listening, using time, demonstrating empathy and building rapport, influencing the other person, and the concept of control. Each skill is further discussed below.

Active Listening

Simply put, active listening is the most important set of communication skills that a crisis negotiator must not only use, but must use properly. The micro-skills of active listening include: using open-ended questions, emotional labeling, mirroring/reflecting, silence, and paraphrasing (read more here). Active listening allows the negotiator to gather important information from the other person (in negotiation terms it is called the interests behind the positions) while it also equally important it demonstrates empathy and rapport.

Active listening is important as it allows the person in crisis to keep talking. That is a good thing- think about the last time you were in a crisis, did you want to talk or listen to the other person (hint: the answer is people in crisis want to talk- not listen!). Active listening allows the other person to talk and your brief comments lets them know they are being heard. This reduces their negative emotions.

The key to active listening being effective is when the micro-skills are used together. It is not just parsing them randomly but rather it must be strategic. For example, use an emotional label followed by an open-ended question. “You sound upset, what happened next?”

Reflect on that for a moment. The emotional label informs the person that you understand their emotion and the open-ended question invites them to continue talking. Trust me, this is really important.

Time

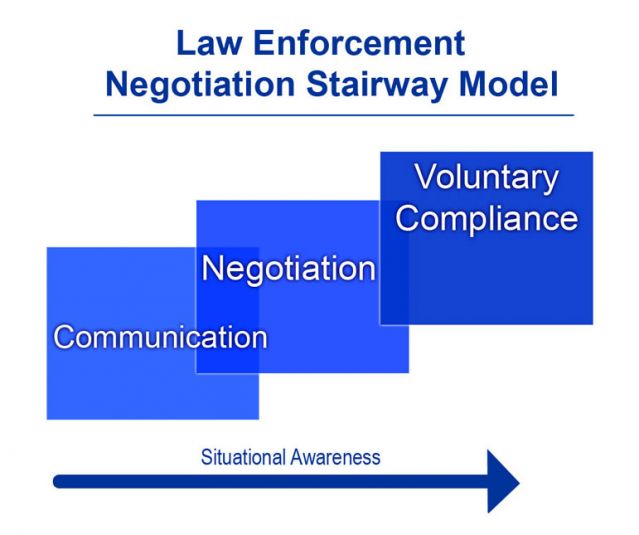

Time is said to be a negotiator’s greatest ally. This simply means slowing things down rather than trying to get a quick resolution. Rushing the process will only add to the negative emotions. We teach the LENS model (Law Enforcement Negotiation Stairway) to police negotiators which reminds our negotiators to slow it down and much like it makes more sense to take one step at a time when going up stairs, it makes sense to take one step at a time when attempting to gain voluntary compliance.

The steps to the LENS Model are:

- Communication: Listen more than you talk

- Negotiation: Allow the person to be part of the decision-making process

- Gaining voluntary compliance: Remember, that is your goal!

Using each step helps slow the process down and allows the other four skills to be used.

Empathy and Rapport

If we as negotiators are trying to influence a behavioral change in the person, it is necessary to understand their current emotions and behavior. Empathy is just that- seeing and understanding the perspective of another. You need this in order to be an effective negotiator and you need to demonstrate it by taking your time to listen (yep, a pattern is developing here—each of the five skills work off of each other). Read more on the general importance of empathy here (really, I suggest you read it).

Building rapport involves giving the person your attention, being positive, and coordinating your communication. It is no surprise then rapport relies heavily on active listening. In order for rapport building to be effective, you have to ensure your verbal and nonverbal communication is congruent. This includes your voice tone, using open-handed gestures, and having eye contact.

Influence

Using the previous skills allows you as the negotiator to de-escalate the situation. In police situations, we are there to negotiate and try to resolve the immediate crisis at hand. There is a purpose to slowing the process down and using active listening to demonstrate empathy and build rapport—it is not just to build that connection with them. Negotiation 101 tells us to have a goal and not lose sight of it. It is the same in other negotiations; you are trying to get something.

Gary Noesner, retired FBI Chief Negotiator, explains this by saying the following:

"We all need to be good listeners and learn to demonstrate our empathy and understanding of the problems, needs, and issues of others. Only then can we hope to influence their behavior in a positive way.”

Control

If a person is in crisis, the odds are they feel like something important is missing- control. A person in crisis often feels like they have no control over their life and that is what pushes them into a crisis. Making that person be part of the decision process is vital to ultimately getting what you want. In non-police negotiations, it will most likely involve having to “give a little” to “get a little.” It is called negotiation for a reason. Let the person be part of the process (instead of demanding). Allowing them to be part of the process starts with letting them talk and it continues with them being part of the negotiation process.

One of the first things we teach police officers is that by giving the other person a sense of control does not mean giving up your control. It is the same for you when you are involved in a crisis situation that includes you negotiating. The goal is voluntary compliance (note the voluntary part of it). Ultimately you have to decide what your other options and then decide what is best for you.

Keep in mind you also have to keep control of yourself- especially your emotions. Emotions are contagious, and if you are entering a crisis situation where the other person's actions are being dictated by a variety of negative emotions, you want to make sure you are not getting caught up in their emotions. Rather, by controlling yourself (voice tone and other nonverbal cues) your calmness can help de-escalate the tense situation.

Conclusion

Crisis negotiation in law enforcement requires many hours of training initially and then continued practice through one’s career. Practice involves role-plays and scenarios while also being up to date on the latest research. These situations often literally are life and death. The skills mentioned in this article have been proven to help gain voluntary compliance and reduce harm to those involved. If these skills work in these situations, they very well can help you in your next crisis. All it takes is practice.