Charisma

Is Charisma a Gift—or Can It Be Trained?

10 insights into the mystery of charisma.

Posted February 22, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Think of someone—a famous politician or a childhood friend—who is charismatic. Someone who lights up rooms and hearts with their mere presence. What is behind their allure? Their looks? The way they move and talk? Their personality and attitude? Their accomplishments?

Charisma, which in Greek means “a divine gift,” is often veiled in mystery. A century ago, sociologist Max Weber wrote about charisma as a “supernatural” quality that was reserved for a lucky few. It’s ambiguous and undefinable, yet we recognize its spell easily—whether on our screens or in our living rooms.

John Antonakis from the University of Lausanne has been investigating charisma for over a decade. He is in the business of demystifying and democratizing charisma, he says. While dissecting something commonly deemed mystical to its bare components may seem like turning on the lights during a magic show, Antonakis has come to a startling conclusion: Charisma can be learned. Rather than it being a sacred endowment reserved for "special people," most of us can boost our charisma levels with the help of a few tricks. Moreover, these tricks—known as charismatic leadership tactics (CLTs)—have been shown to be effective as much in research laboratories as in the real world: in classrooms, boardrooms, and presidential elections.

Together with his colleagues, Antonakis investigates how the way we speak and what we say drives much of charisma. The premise is simple: If a person (let’s call them X) wants to ignite the charismatic effect, he needs an observer (let’s call them Y). To win the attention, trust, and reverence of Y, X must communicate his ideas in a way that will help them understand his message, relate to it, and remember it. In other words, X must form an emotional connection with Y. This is where the tactics come in. By fertilizing their speech with metaphors, stories, and images and by delivering it with the right voice and gestures, speakers can ignite their X-factors and exude effortless charm in the eyes of their audience.

Although science has come a long way in exploring the alchemy of charisma, there still remains a lot to uncover of its secrets. Yes, it’s astounding to gain insights into the psychology of inspiration; to see how the Aristotelian philosophy of ethos, pathos, and logos prevail in capturing spectators; to stock our toolboxes with tricks for communicating, connecting, and influencing; to learn how to rouse emotions, instill dreams, and change lives with our words. And yet, one can’t help but wish that some things—about our humanity, our attractions, the spells we can cast on each other—stay safely inexplicable. Just like a magician and his mysteries. Just like Charis, the goddess of charm in Greek mythology, and her grace.

Here are 10 insights into charisma from Antonakis.

What makes someone charismatic?

Charisma can come from different sources, including looks, behavior, and speech. Actors like Marilyn Monroe are charismatic, initially, because of their looks. Athletes may appear charismatic because of their exceptional abilities on the field. Even knowledge about someone’s previous performance, such as their accomplishments or creativity, can make them appear charismatic (e.g., Steve Jobs). A lot depends on how well you know the person. If you don’t have much information about them, then looks and performance signals play a big role. If you do—like with candidates during an election—then speech matters more and could even override looks.

Is charisma a personality trait, a skill, or a gift?

It’s a combination of nature and nurture. Whereas some people may have an innate ability to be more charismatic, Antonakis views charisma as “an emotional, symbolic and value-based leader signaling.” When we first meet others, we rely on these signals to communicate our competence and confidence and to close the gap in our understanding of each other. These signaling mechanisms are trainable. Some people have learned various tactics through experiences and role models and use them without even realizing it. Others need more practice.

Although it helps to have intelligence and extraversion, having magnetism has a lot to do with speaking in a way that will attract the attention of others. As to whether charisma is a “gift,” because researchers can study charisma scientifically, measure and train it, and because computer programs can now identify how well people use rhetorical skills and body language, Antonakis deems it more of a learnable (rather than divine) kind of gift.

Why is storytelling a key ingredient of charisma?

Historically, good storytelling skills had an evolutionary advantage. Being able to communicate information about important lessons or morals and how to do things appropriately in a given environment helped people survive. Nowadays, we rarely gather around campfires telling stories; however, charismatic people still possess these much-cherished abilities. Storytelling is attractive across all societies. If someone is good at telling a story and explaining something that will help us solve a problem, then we imbue them with charisma. We assume they have unique abilities to see the future and know how to handle things. “In everyday life, people who are influential and get their way have the ability to capture attention,” says Antonakis. “And telling a good story is one way of capturing attention.”

Can charisma be learned?

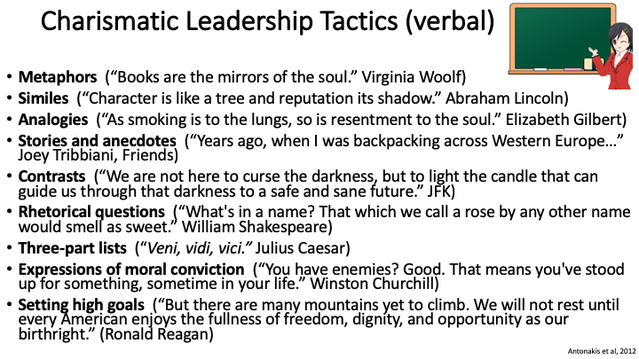

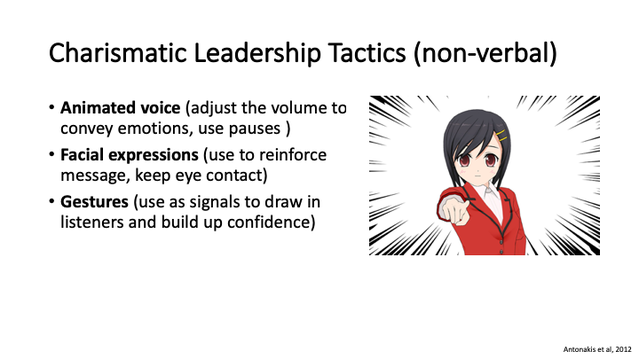

It’s not only leaders who can benefit from honing their charisma. These skills can be useful in a variety of settings and professions that draw on forging emotional connections with others. Antonakis and his colleagues have identified 12 key CLTs (nine verbal, three non-verbal) that have shown to increase the speaker’s charisma and make them appear more influential and trustworthy. In his own training, Antonakis asks participants to give a speech on a certain topic. Then, after extensive explanations and illustrations of charisma theory, the speeches are rewritten to include CLTs. Then, it’s time to practice the delivery—this time with the help of non-verbal tactics.

How is charisma measured?

To measure charisma, researchers like Antonakis analyze the way people speak. Sentence by sentence, they look for the presence of the nine charismatic tactics. They also look for how people speak—their voice, gestures, facial expressions. Antonakis has found that when it comes to charisma, the power of words trumps non-verbal behaviors. “I can be gesticulating wildly, but if I’m talking nonsense, I won’t come across as charismatic,” he says. Consider leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Margaret Thatcher, Nelson Mandela, and Kofi Annan. Whereas they are widely regarded as charismatic, their use of non-verbal behavior in their speeches was very limited, Antonakis notes: “Annan spoke in a flat voice; you could hardly hear Gandhi speak; Mandela wasn’t the best articulator; Thatcher was even-tempered and did not gesture much. And yet, when they spoke, they left their audiences entranced.”

How do you know if you have charisma?

Consider how much influence you have over others, suggests Antonakis. But remember, a key ingredient in the charismatic effect is the overlap in values. Even if you have abundant charisma, it won’t necessarily be easy to win over others if they disagree with your values. Charismatic leaders can be loved by those who share their values and loathed by those who don’t.

Does charisma travel across cultures?

Do highly charismatic people appear charismatic in other countries? According to Antonakis—yes, charisma travels across cultures. Verbally, that is. When Antonakis and his team analyzed scores of political speeches and TED talks from around the world, they found that those who were considered charismatic in their native languages were using a lot of the same techniques in their speeches. Indeed, the evolutionary significance of storytelling is universal, since it helped people to visualize information, retain it, and then pass it on. Thus, according to Antonakis, humans are pre-programmed to be attracted to others who use these charismatic techniques when they speak. What does differ across cultures, Antonakis has found, are the values that people communicate in their speeches and their non-verbal behaviors.

Why are we attracted to charismatic people?

Various psychological factors are behind our attraction to charismatic individuals. One key factor, according to Antonakis, is identification. We identify and connect with them. We want to emulate and please them. It’s as if charisma dons a halo around individuals, often making them appear more appealing to others. Moreover, charisma may have evolved as a credible signal of a potential leader’s ability, much like the signals animals use to infer fitness and strength.

Can you fake charisma?

“Charisma is difficult to fake, because you’ll be discovered sooner or later,” says Antonakis. For example, if a leader is creating high expectations by communicating certain values and building his speeches on beguiling metaphors and vivid stories, but keeps breaking his promises and values, he will lose his trust and credibility in the eyes of the people. And, with it, his charisma.

What is the biggest misconception about charisma?

There are four major misconceptions about charisma that Antonakis has discovered through his research.

- Humility is more important than charisma in company performance. “This argument was made in a bestselling book, but was based on flawed statistical design.”

- The Hitler Problem: Charisma has earned a bad name, because history is marred with charismatic despots. “Charisma is not correlated with being an arrogant bastard,” Antonakis says. “We have had many leaders who are humble and charismatic at the same time, like Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi, Mandela. Charisma, like money, power, or science, can be used for good or bad.”

- It’s a gift—you either have it, or you don’t. “It’s more like a skill—it can be trained and developed.”

- It does not matter much. “Totally untrue,” Antonakis asserts, “Our research shows that not only charisma can increase worker performance as much as monetary bonuses, but charisma can also explain who wins elections and what tweets or TED talks go viral.”

Many thanks to John Antonakis, a professor of Organizational Behavior at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, for his time and insights. His research is focused on charisma, predictors of leadership, and research methods.

Facebook image: mimagephotography/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: GaudiLab/Shutterstock

References

Antonakis, J. (2017). Charisma and the "New Leadership". In J. Antonakis & D. V. Day (Eds.), The nature of leadership(3rd ed., pp. 56-81). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Antonakis, J., d’Adda, G., Weber, R. A., & Zehnder, C. (2015). Just words? Just speeches? On the economic value of charismatic leadership. NBER Reporter, 4.

Antonakis, J., Fenley, M., & Liechti, S. (2011). Can Charisma Be Taught? Tests of Two Interventions. The Academy of Management Learning and Education, 10(3), 374-396.

Antonakis, J., Fenley, M., & Liechti, S. (2012). Learning charisma. Transform yourself into the person others want to follow. Harvard business review, 90(6), 127-30.

Antonakis, J., Bastardoz, N., Jacquart, P., & Shamir, B. (2016). Charisma: An ill-defined and ill-measured gift. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 293-319.

Jacquart, P., & Antonakis, J. (2015). When does charisma matter for top-level leaders? Effect of attributional ambiguity. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1051-1074.

Tur, B., Harstad, J., & Antonakis, J. (2018). Effect of Charisma in Informal Leadership Settings: Evidence from TED and Twitter. Academy of Management Conference, 13242.