Relationships

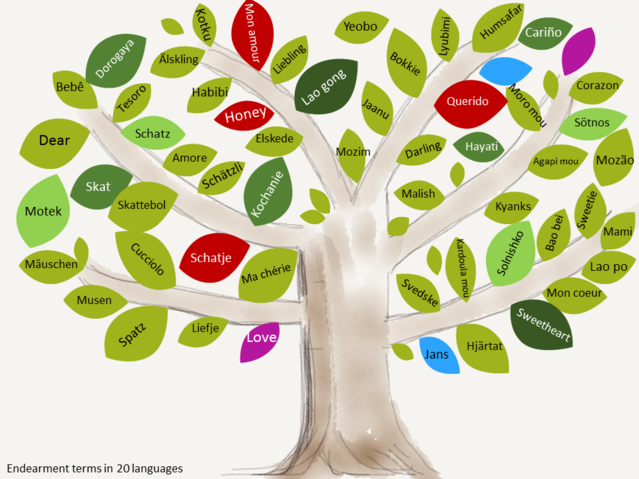

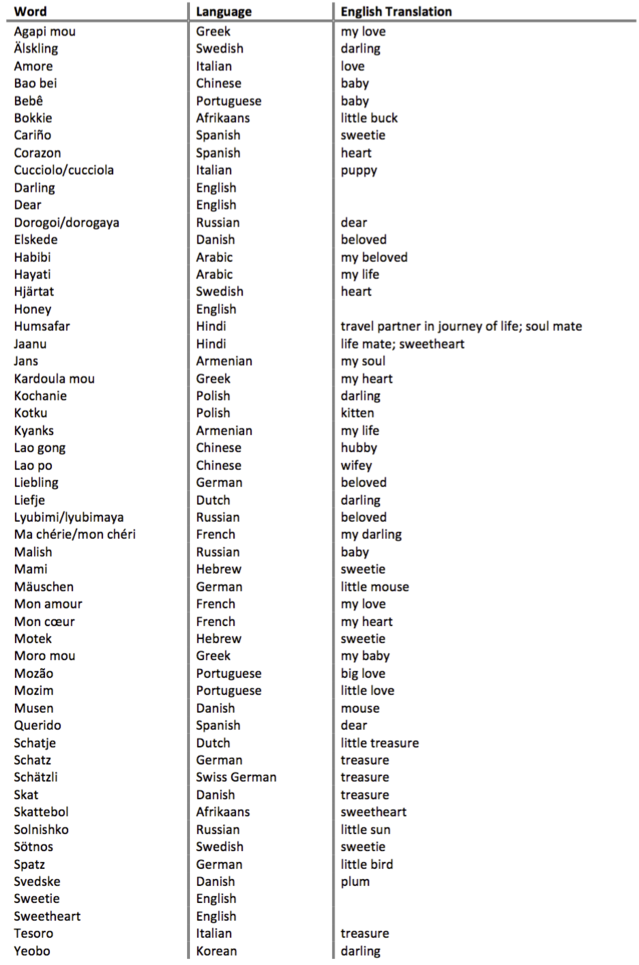

Terms of Endearment in 20 Languages

How we express love - from humorous to poignant - varies.

Posted February 10, 2016

At the touch of love, everyone becomes a poet. Plato

Whether in the beginning, when love feels like “quivering happiness” (Khalil Gibran) and “madness” (Pedro Calderon de la Barca) and “smoke made with the fume of sighs” (William Shakespeare), to when seasons pass, turning it to “a state of grace” (Gabriel Garcia Marquez) and “immortality” (Emily Dickinson), love - or l’amour, or lyubov, or by whichever name it wanders the four corners of the world - is the sublime universal of the human condition. It has been called many a name at the lips of lovers and poets, and with no less fire, dissected by the pens of philosophers and scientists alike. For some scholars, love is a basic emotion; an emotional attitude and a “plot” to others; a sentiment and a motivation system for yet others. Most theorists agree that love is not a single emotion. Rather, it is a blend or a first-order dyad of a number of emotions (e.g., joy and acceptance), with neurochemical processes involving different neurotransmitters and hormones, and activations of certain dopamine-rich regions of the brain associated with reward and motivation (e.g., VTA, caudate nucleus), all of which affect our cognitive and behavioral patterns.

It’s not everyday we confess our affections to our beloveds through sonnets. Yet, love still finds ways to slip quietly through the words we use to address each other during our ordinary hours. How we express love - from superfluous to ascetic, from humorous to poignant - varies. The variations depend on a myriad of factors, including the relationship’s own mini-culture, as well as the bigger culture of where the love is embedded. Couples often engage in idiosyncratic communication with the help of idioms, nicknames, pet names and endearment terms. Defined by “context and function” rather than semantic characteristics, terms of endearment leave plenty up to linguistic creativity and imagination of individuals (Braun, 1988:10). Any noun can turn to a form of address and any word can become a private pair-bonding idiom. The use of such insider language has been shown to be associated with increased levels of relationship satisfaction among couples. Moreover, it can help build relationship cohesiveness and identity. The use of endearment terms and personal idioms is fluid and ever-evolving, depending on the stage of the relationship, with one study showing that couples in their first five years of marriage without children used the most idioms.

I asked native speakers of 20 languages for some of the most common endearment terms used among couples in their languages. Here they are, standing under different names and voices, speaking for the same emotion, sentiment, “plot”.

Then again, as sweet as our endearments may be, there is a time in most tales of love, when the sound of a certain constellation of syllables, the sight of a particular sequence of letters, is filled with magic that only the name of our beloved’s can bear.

References:

Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D., Strong, G., Li, H., & Brown, L. (2005). Reward, motivation and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 94 (1), 327–37.

Braun, F. (1988). Terms of address: Problems of patterns and usage in various languages and cultures. (Contributions to the Sociology of Language 50.) Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bruess, C.J. & Pearson, J.C. (1993). ‘Sweet pea’ and ‘pussy cat’: An examination of idiom use and marital satisfaction over the life cycle. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10 (4), 609-615.

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6, 169-200.

Ekman, P. (1984). Expressions and the nature of emotion. In K.R. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion (pp. 319-343). Hillsdale, N J Erlbaum.

Fisher, H., Aron, A., & Brown, L.L. (2005). Romantic love: an FMRI study of a neural mechanism for mate choice. The Journal Of Comparative Neurology, 493, 58-62.

Fisher, H., Aron, A., Mashek, D., Li, H., Brown, L. (2002). Defining the brain systems of lust, romantic attraction and attachment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31 (5), 413-419.

Frijda, N. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Hopper, R., Knapp, M.L., & Scott, L. (1981). Couples’ personal idioms: Exploring intimate talk. Journal of Communication, 31 (1), 23-33.

Jankowiak, W.R. & Fischer, E.F. (1992). A cross-cultural perspective on romantic love. Ethnology, 31, 149-155.

Landau, E. (2015). Why do we use pet names in relationships? Scientific American, February 12. Retrieved from http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/mind-guest-blog/why-do-we-use-pet-n…

LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Schuster.

Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotions: A Psychoevolutionary Synthesis. New York: Harper & Row.

Shaver, P.R., Morgan, H.J., & Wu, S. (1996). Is love a “basic” emotion? Personal Relationships, 3 (1), 81-96.