Anthropomorphism

Why Reptilian Brains Are Comparable to Our Own

Do reptiles have feelings? A surprising perspective emerges though a new lens.

Posted December 19, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

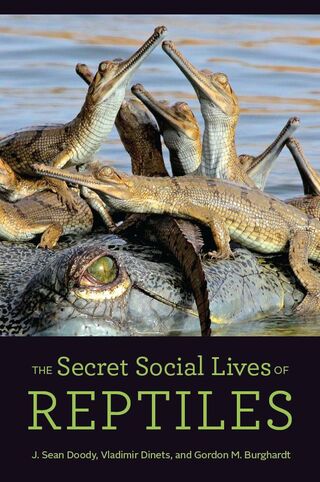

Neuroscience demonstrates that all reptiles possess brains and neuro-capacities comparable to our own. In this interview, Gordon M. Burghardt, Alumni Distinguished Service Professor of Psychology and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee, and co-author with J. Sean Doody and Vladimir Dinets of the new The Secret Social Lives of Reptiles (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021) shares insights from decades-long studies into the psychological world of ectotherms:

GAB: Neuroscience has established that snakes, turtles, and other reptiles possess brains comparable to our own. Furthermore, the popularized triune brain model as an evolutionary progression is incorrect: There is no such thing as a “reptilian brain.”

GMB: Yes, neuroscience confirms what I and others have observed for years in the field: Animals, including reptiles, have many psychological capacities comparable to our own. Actually, among the major groups of vertebrates, ‘reptiles’ is the most diverse. Turtles, crocodilians, snakes, lizards, the tuatara, and birds differ among themselves far more in many features than we differ from mice or otters. We are still so mammal-centric and biased that we fail to appreciate the mental and emotional sophistication of reptiles.

GAB: Why haven’t emotions and sociality been associated with reptiles?

GMB: One main factor is that reptiles have more rigid faces than mammals, and thus humans do not detect and recognize expressions that may indicate moods or emotion. Snakes and lizards appear to lack facial expressions that we consider so important in everyday life interacting with family, friends, colleagues, and strangers, and that we use to “read’ other species such as dogs. Furthermore, unlike birds, reptiles are generally not very vocal. They don’t make the same kind of utterances that we understand.

GAB: What are some examples of reptile social and emotional intelligence?

GMB: Long-term parental care found in many crocodilians (crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gharials) is one of the best examples. Mothers retrieve hatchlings from the nest they have guarded for months and carry their infants to the water. They may care for and protect their young for up to two years. Our new book, The Secret Social Lives of Reptiles, shows a male gharial, a large, highly endangered crocodilian who protects and carries dozens of babies on his back, many of which may not actually be his own. The highly monogamous Australian sleepy lizard, a large skink, forms pair bonds that may endure more than 25 years.

GAB: What are some of the most outstanding discoveries you have made and experienced with specific reptiles?

GMB: There are many moments when I was privileged to discover or document something that had not been known or scientifically recognized. The majority were discovered through experiments, but I will just mention some moments of personal epiphany. Perhaps the earliest occasion was when I found out that newborn snakes who had never eaten anything in their lives could recognize, purely by chemical cues, the prey they “should" eat by biting at cotton swabs coated with chemicals from the surface of prey, such as worms, fish, and frogs. This discrimination ability varies by species depending on their species-specific diets. Reptiles are not automatons, but adaptive decision-making creatures. More recently, I have been spending time interacting with a Komodo Dragon at Zoo Knoxville and watching how she liked to play with balls, buckets, and bags and bond with keepers and even myself. Witnessing such deep and sensitive intelligence up close is thrilling.

GAB: You developed the concept of "critical anthropomorphism" — also referred to as bi-directional inference.

GMB: Conventionally, observations without experimental support were considered a poor basis for studying animal minds, emotions, and behavior, especially by psychologists. I found that by seeing past the projections of animals as “less than” or mere alien “machines” controlled by conditioned and unconditioned reflexes and instincts was key for inspiring new ideas. These insights can lead to more formalized, systematic study.

By being open to getting to know individual animals as one might a human, critical anthropomorphism helps us distinguish useful observations from those based on biased and uncritical interpretations. It simply entails putting yourself in an animal’s shoes, and thinking about how you might react in a similar situation if you had the attributes s/he possessed. There is no legitimate justification to dismiss so-called “anecdotes” – keen, first-hand observations made by astute and well-trained naturalists – which provide great insights into the perceptual, cognitive, and emotional responses of nonhumans. Ironically, scientific and public prejudice against reptiles is a perfect example of anthropomorphism.

GAB: Is approaching nonhumans akin to how an anthropologist might approach diverse human cultures?

GMB: Yes. A good cultural anthropologist goes into the field knowing they share with individuals of another culture major mental, perceptual, physiological, and behavioral components as well as similar life events and transitions such as courtship, marriage, parental care, sickness, and death. Yet, they also realize that language, cultures, ecology, and social arrangements might differ greatly from the norms they have experienced. In the same way, a scientist studying the psychology and lifestyle of a snake or turtle, for example, has to be open to both similarities and differences in behavior and internal mental constructions. some of which may be unexpected.

GAB: Have you observed trauma in reptiles?

GMB: Yes, and the second edition of Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles by Clifford Warwick and Phil Arena details problems of reptile stress and trauma. The book functions as a guide to the recent groundswell of studies on reptile physical, psychological, and behavioral wellness and well-being – and the psychological suffering that they endure. Reptiles are social, emotional, and sensitive. This has to be how they are approached, understood, and respected.