Asperger's Syndrome

Why Claim Asperger's is Overdiagnosed?

Certainty but no evidence from some clinicians and researchers

Posted November 21, 2012

In my previous post I looked at the arguments against retaining the Asperger Syndrome label, which will be dropped from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth edition, to be published in May. I held this one back to save it the indignity of being stuffed into a closing paragraph. Not that it deserves dignity.

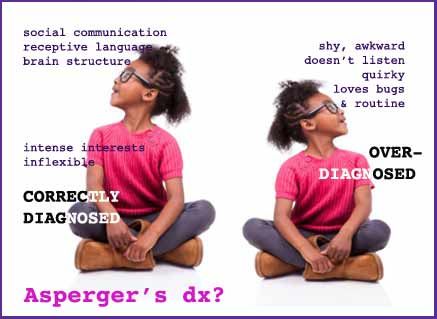

AGAINST: The Asperger’s diagnosis has been too liberally applied, pathologizing social awkwardness and straining educational budgets.

While the American Psychiatric Association insists that “un-diagnosing” is not its goal, there is little question that a purpose of its DSM changes is screening out those who may not be “definitively” autistic. Members of the committees charged with the autism revisions have reverted to this theme again and again, often in unguarded moments.

Proponents of the over-diagnosis argument don’t provide supporting data. That’s because there aren’t any. On the contrary, Francesca Happe, a member of the relevant DSM-5 workgroup, referred in a 2011 editorial to studies indicating “clinicians show good agreement about who falls within versus outside the autistic spectrum.”

It’s true that as a society we are given to casual overdiagnosis, if inexpert speculation about celebrities can be called diagnosis. A recent New York magazine feature cited public discussion of the Aspergerian nature of numerous contemporaries, starting, in nonpartisan fashion, with Mitt Romney and Barack Obama. I have my reservations about such diagnostic speculations. But still, I'm never convinced that they're only problematic, and certainly they're not specific to Asperger's. Inevitably, terminology from psychology and psychiatry, as from other fields, jumps from clinical to casual use and can be inaccurately applied. But the Asperger’s jump (like our frequent, often glib references to ADHD and other conditions) signals our expanding awareness of ourselves and others, our interest in neuropsychological diversity. It makes many of us pause before judgment.

Although the clinical understanding of autism influences casual conversation, casual conversation should not influence the clinical understanding of autism. And yet it so frequently does. The overdiagnosis argument, in which Asperger syndrome is accused of a major role in the alleged over-medicalization of the American population, is a prime example. It is particularly unnerving when it comes from DSM-5 professionals, since it suggests pre-emptive justification for “undiagnosing” a significant cadre of autistic people. (Some of those professionals prefer to blame Fred Volkmar, director of the Child Study Center at the Yale School of Medicine, for the public anxiety.)

In February, science writer Emily Willingham delivered an intricate critique of the flabbery jabbery coming from some of these autism “experts”: anecdote cited as evidence, opinion as certainty. A less measured commentator accused the DSM team of pseudoscientific delusional syndrome. Some of the overdiagnosis comments sampled below have achieved notoriety in the autism community, but still, the Asperger’s Alive! archive would be remiss not to include them. And its worth remembering that social communciation and Theory of Mind present challenges for some autism researchers.

- Susan Swedo, chair of the DSM-5 neurodevelopmental disorders workgroup, said in May that many people who identify with Asperger’s Syndrome “don't actually have Asperger's disorder, much less an autism spectrum disorder.”

- David Kupfer, chair of the task force charged with the DSM revisions, blurted to the New York Times in January: “We have to make sure not everybody who is a little odd gets a diagnosis of autism or Asperger Disorder. It involves a use of treatment resources. It becomes a cost issue.” (This was startling to those who’d missed the memo that declared costs and treatment resources the responsibility of the APA. Which was everyone.)

- Catherine Lord, the director of the Institute for Brain Development at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, and another member of the workgroup, told Scientific American in January, “If the DSM-IV criteria are taken too literally, anybody in the world could qualify for Asperger's or PDD-NOS... We need to make sure the criteria are not pulling in kids who do not have these disorders.”

- Paul Steinberg, a D.C. psychiatrist, declared in a New York Times op-ed in January that “with the loosening of the diagnosis of Asperger, children and adults who are shy and timid, who have quirky interests like train schedules and baseball statistics, and who have trouble relating to their peers” are erroneously and harmfully labeled autistic. He blamed a 1992 Department of Education directive that “called for enhanced services" for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: “The diagnosis of Asperger syndrome went through the roof."

- Dr. Bryna Siegel, a developmental psychologist at the University of California, San Francisco, told a Daily Beast reporter in February that she “undiagnoses” nine of out ten students with so-called Asperger’s. Siegel was a member of the panel responsible for the inclusion of Asperger’s in the DSM-IV, which the reporter cited to me in a phone call as evidence of Seigel's objectivity: implicitly, Seigel is critiquing her own work. But that same journalist made no mention in the piece of Dr. Seigel’s history as an expert witness for school districts fending off families’ claims for those “enhanced services,” and the obvious conflict of interest (as well as the selection bias in her client pool) this represents. In October, she told New York magazine that she undiagnoses six out of ten. That's quite a shift in eight months. Hope it was evidence-based.