Therapy

Art Therapy in Prison—Now That’s Sexy!

Many find prison art titillating; some come to realize it is so much more

Posted October 27, 2015

When I first began at Florida State University 14 years ago, the Department Chairperson set up a meeting to discuss my research agenda. I confess, after being involved with prison work for more than 10 years at this point, I had wanted to get away from corrections. Quite frankly, I was pretty much burnt out after being in and out of prisons all those years… for work.

During our conversation, I suggested that I might pursue my dissertation topic further—one that was as far removed from corrections as I could get without a court order. After letting me ramble for around 15 minutes, she finally spoke up: “Yeah, that’s fine…but what about that art therapy in prison stuff? Now, that’s sexy.”

After a moment’s silence, I laughed; then after considerable discussion, we agreed on a compromise— I would continue to explore the value of art and art therapy in prison.

I must admit, I found this interchange funny and even after 14 years I continue to recount it in presentations and addresses—certainly, there must be something about this work that draws people in. But, is it really sexy?

And if so, why, and how does this affect the message?

Recently, two of my graduate assistants, Ashley Beck and Carla Clymo, and I sat down to discuss why people were attracted to this topic.

We ruminated on how, between the television programs Oz, Prison Break, and Orange is the New Black, our culture was so captivated by prison. Are we fascinated because we simply want to understand this hidden subculture? Does the fascination stop at understanding? Is it because of our voyeuristic tendencies?

Or, perhaps is it that these television programs force us to consider those we lock up to forget? And, in doing so, they may in fact break down the rigid boundaries that separate us and remind us that inmates are indeed real people. And, as real people, we come to realize that we could be them. In other words, do we enjoy the titillating yet apprehensive insight: “there but by the grace of God go I…”?

This is not the first time I have considered this.

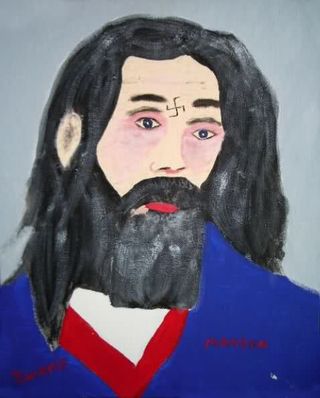

Last year’s blog post, “Art of Murderers”, considered that “oftentimes, I would show art pieces that would not otherwise earn a second glance. However, once someone is told the artist murdered someone, viewers linger over the piece with fascination and disgust. Such curiosity is reminiscent of rubbernecking—a perverse desire to gaze on the results of a horrendous act.”

This fascination can be carried forward to include all inmates.

Furthermore, Carla raised a very significant question: Can we, and should we, separate the person’s life from the art? Being aware of the context and of the person’s criminal background may make it hard to consider the artwork for what it is. This knowledge of the person’s moral infractions tends to affect our perception of his/her art. We look at it not as a piece of art, but as a criminal’s piece of art, and we tend to decrypt it in that way.

Is it, therefore, morally acceptable to view an artwork as beautiful, potent, or successful, if we know in advance that the person who made it has been deemed beyond the pale? Should we feel guilty for admiring the output of someone who committed a heinous crime, or, contrarily, should we disregard the work because of its creator?

Some people’s reaction may also be tinged with anger and disgust (“why are you offering these criminals services? They have nothing coming to them”). But even these responses, charged with biased negative emotions, still evoke a sense of humanity and awareness, furthering the dialogue beyond mere apathy and disregard—the opposite of respect and love is not hate but rather indifference. If you have a strong emotional response, dehumanizing the recipient is no longer possible.

Art, we hope, seems to evoke humanity in most people. They associate it with expressiveness, sensitivity, creativity – in sum, traits that seem antithetical to those assigned to prisoners. Even people who do not consider artistry a real career admire artists. Hence, the apparent paradox.

This perhaps revisits the core issue of emphasizing the humanity in the “worst” criminals and allows us to question what separates them from the rest of us—if anything.

Once again, pop culture holds the mirror up to our society and forces us to examine the very issues. Allow me to digress; why is Orange is the New Black so successful? In a lecture and discussion last winter, the book’s author, Piper Kerman, indicated that since she was released, she has chosen to highlight the unjust in the justice system. And her message is potent. As an educated woman from the upper echelons of society, she reminds us that anyone could be caught in this system. She does what is most dangerous to the success of this “correctional system”—she puts a human face on the inmate.

Piper Kerman draws crowds to her talks and some people even find her alluring and her television counterpart sexy. Yet, the book reveals that her experience is anything but. It clearly illustrates the mundane, the boredom, the repression, the fear—it ain’t sexy. But sexiness brings people in to listen.

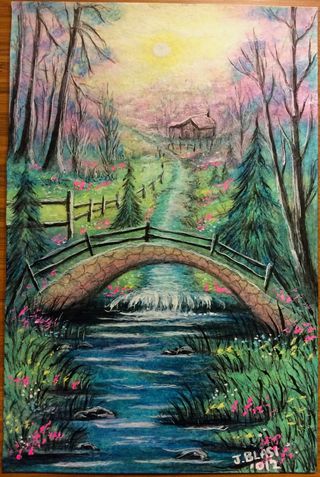

The same can be said about the art. Prisoners make art as a reaction to the mundane, boredom and repression—it captures their escape, not their imprisonment. But their art brings people in which in turn accentuates their lost humanity.

“We get a lot of people asking if they can start a Bible study group in here but nobody asks about bringing an art class inside. We would love to have you.”

Ashley discussed her experience prior to being an art therapy graduate student at Florida State. She approached a prison in the south to offer her services as an artist by starting an art class for women with lengthy or life sentences. The above quote was the chaplain’s reaction when asked if she could do so.

Knowing she wanted to pursue art therapy, she wanted to make community art and provide opportunities for people who didn’t have access to healthy expression. Prison, for some reason, interested her. As she indicated “I, too, was intrigued by prison shows and loved Prison Break. I think their (the inmates') situation intrigued me. I knew that art could be their only means of escape from their mundane prison routine. In a few short weeks, the Warden approved the class and I was in. Some inmates attended because they were interested in learning how to paint. Others wanted help 'calming their nerves'. And the rest said they needed an outlet for their pent up emotions so they could avoid going back to Ad Seg (Solitary Confinement—please see a related blog post here). I showed their work in the college gallery space at the end of the semester; in this way, I valued them as individuals: these people, though incarcerated, have something to say and something to give.”

And, people attended the show. People, who might otherwise not have given a second thought to those locked up.

Perhaps my Department Chair was right; art therapy in prison is sexy. Yet, while sexy brings people in, the art reveals the humanity, illuminating that which society hides.