Relationships

Sustanimalism: A Unique View on Human-Nonhuman Relationships

A guest essay by Dr. Pim Martens, founder of the “think and do tank” AnimalWise.

Posted September 25, 2020

"Some people talk to animals. Not many listen though. That’s the problem." —A. A. Milne

"More respect for animals and nature is key to a sustainable society.” —Pim Martens

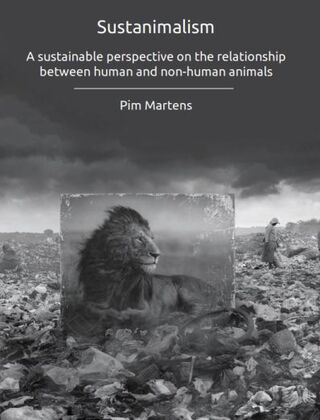

I'm pleased to post this guest essay by Prof. Dr. Pim Martens, Professor of 'Sustainable Development' at Maastricht University (Netherlands) and Senior Fellow in the Ethics of the Anthropocene Program at the Free University, Amsterdam, about his new book Sustanimalism: A sustainable perspective on the relationship between human and non-human animals, available for free at Global Academy Press. Pim is the founder of AnimalWise, where knowledge and science meet ethics and compassion—a “think and do tank” integrating scientific knowledge and animal advocacy—to bring about sustainable change in our relationship with animals.1

If we look at the many sustainability indicators that have been developed over the years, it is striking to see that animal well-being hardly plays a role. Biodiversity and ecosystems indicators put more emphasis on the number and variety of different species than their well-being. Assuming that the words of Gandhi make sense, can we then conclude that the concept of sustainability has nothing to do with civilization? Or is it that animal well-being is a blind spot in the sustainability debate?

Of course, our interaction with the environment, other people and other animals is part of our civilization. The reason that "animals" and "sustainability" are not often mentioned together in one sentence is likely to be found in the fact that the sustainability debate has been hijacked in recent years by industry and governments; their view regarding sustainable development has significantly been subordinate to the dogma of economic growth with little regard for animal welfare. How short-sighted this is has been illustrated by the various outbreaks of animal diseases in intensive farming and the development of antibiotic resistance of many pathogens, in large part because our farmed animals are given too many antibiotics. These are just some examples, but it is increasingly clear that our own well-being is closely connected with the welfare of the animals with whom we live.

Consider pets, for example. Research shows that people with a pet are in general healthier than non-pet owners. Pets also increase the capacity for empathy and social contacts among children (which are useful characteristics for a healthy and happy life). Furthermore, people who are heavily involved in animal welfare appear to have more compassion for the problems of people. Of course, this supposes good care for the domesticated animals. Keeping animals just because it’s (temporarily) fun, useful, or convenient for us, of course, is not always the most sustainable course of action. We all know stories of neglected pets and there is also a relationship between domestic violence and animal cruelty. Some more examples include the notion that we are happy for animals in the zoo to have large enclosures, but if we have bought a ticket, we do want to be able to see them. Another is that many people like to eat meat, but prefer not to be confronted with pictures of battery cages. We are vegetarian ourselves, but still have a large dog who eats meat. We live in glasshouses.

Although we are at the forefront of animal welfare in Europe and America, there is still much to be gained. But here, too, the situation is often far from ideal. As far as I am concerned, sustainability revolves around how committed people are to the world in which they live. Animals are often ignored in this discussion. It's time to change this. However, "human-animal" research in the context of sustainable development is still in its infancy, and it does not provide us with all the answers. Still, it is an outstanding sustainability issue that deserves our fullest attention from a transdisciplinary perspective. It will also provide the necessary nonhuman elements to the sustainability discussion and will provide a platform for the public debate.

Scientists should be more outspoken when we see that our relationships with our natural environments and the animals within has changed dramatically, causing many undesirable effects as well. For example, more and more animals are kept closely together in unsanitary or overly hygienic (antibiotics, etc.) conditions to satisfy the rising demand for animal protein of densely populated megacities. The need for space and raw materials perpetuates the encroachment on animal habitats such as rainforests, which in turn, brings more humans in contact with more exotic animal species. Add to that frequent international travel—both human and animal—and its excellent conditions for spreading zoonotic diseases such as COVID-19. Scientists are obliged to take more responsibility, especially at times when many signals in nature and society are red.

In Sustanimalism: A sustainable perspective on the relationship between human and non-human animals, I study the sustainability of our relationship with other animals. By looking at animals, you can put the sustainability debate on the map in an engaging way. Animal welfare should therefore be central in sustainability debates: what we term "sustanimalism" (in Dutch, the combination of "dieren" (animals), and "duurzaamheid" (sustainability) leads to the neologism "dierzaamheid"). With this in mind, it is also practical and easy to make a contribution to a sustainable society. Acting animal-friendly, for example, by taking good care of your animals and eating less meat, is not only beneficial to your health but also to a better and more civilized world. I hope to encourage people to think about our interaction with the animals that surround us.

What is sustainable and what is not is not a black and white story, but, by the end of the day, the solution is greater respect for animals and nature: moving away from industrial livestock farming, deforestation, wet markets, and other situations in which nonhumans are abused. My own contribution to science, together with many international scientists, is studying the complexity and interactions between humans, animals, and nature. I hope this book provides a fruitful contribution to this discussion.

References

1) Pim's current work also centers on a very interesting project ‘Religion and Animals in the Anthropocene’. He notes, our dominant current socio-economic and political systems have become decoupled from the larger ecology of life. Our relationship with the natural environment and animals has changed dramatically over time. This project intends to discuss these past patterns and future pathways with (indigenous) religious leaders. Indigenous cultures have a unique view of the world that’s distinct from the mainstream. Learning about indigenous cultures and their relationships with animals may be a way we can begin to address the sustainability challenges we see today.