Making Reason of Insanity

My father murdered his wife—a rare twist made me forgive him.

By Joni West published November 1, 2022 - last reviewed on November 8, 2022

On January 8, 1991, the New York Daily News shouted, “High-Rise Horror” in a gigantic font and “Charge Husband Pushed Wife Out Window,” above a big photograph of my handcuffed father. He had confessed to the police, minutes after the murder, that he had beaten my stepmother to death and thrown her body out of their posh, 12th-floor, Manhattan apartment window to make it look like a suicide.

The shock hit me as my brother told me the news over the phone. I immediately sought to confirm that I was awake and not dreaming. I examined myself in the mirror. I didn’t expect my image to follow my movements because this couldn’t be happening in real life, not in my real life.

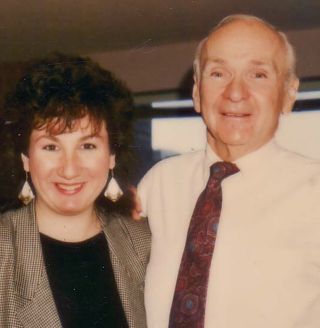

My father, Herbert Weinstein, told the police that the argument started when my stepmother made disparaging comments about me and my brother. The police, journalists, and everyone who heard about the murder believed that he had flown into a rage because my stepmother was insulting his children. That was a plausible narrative to them, but not to me. I knew my father was not like other people. I thought he was unique, but in the most fabulous way.

He was always in a great mood. If you asked him how he was, he always answered, “Terrific!” “Fantastic!” The annoyances of life, even very grating people, never made him frustrated, stressed, or angry. My dad was a Swiss Army knife of solutions, happiness, and love for me. He made everything I pursued feel fun and important. As a kid, I was obsessed with photography, and he made sure I had the best of everything—cameras, darkroom equipment, books, and film—to pursue my passion. He even took me to New York City to visit museums and galleries, times I cherished.

My dad made everything right in my world. When I reported the impossible-to-avoid transgressions I had committed that had infuriated my mother on any particular day, he would simply say, “That’s your mother,” and stretch his arms out for a hug. He didn’t suggest that he or I should try to change her. He would cheerfully dismiss the matters at hand by saying, “You know the truth, and I know the truth. That’s all that matters.”

Herbert Weinstein owned and ran the company that controlled the advertising licensing rights for public buses in New Jersey. People found him charming, and his phenomenal salesmanship made him successful. He took excellent care of my mother when she got cancer, never leaving her side for the two years she suffered. She died when I was 20. My father met Barbara a month later and married her the following year.

My relationship with Barbara was difficult from the start. When I complained about my stepmother’s behavior toward me and my brother, his response was, “That’s Barbara.” I knew that the insults she was hurling at the time he killed her were nothing new. She had said them to him before, and he had always ignored them. That’s why the narrative that he flew into a murderous rage over them made no sense to me.

My father lived by a code—something we called Weinstein Wisdom. He was remarkably consistent in his behavior and adherence to his own rules. He used certain phrases so routinely that they became mantras in our family, including: “Always tell the truth.” “Say what you mean and mean what you say.” And, “Don’t concern yourself with what other people think.”

My favorite bit of Weinstein Wisdom was a shortened version of the Optimist’s Creed: “Look at the doughnut, not at the hole.”

Shortly after their marriage, I started to notice something new—my father had developed a lack of empathy. Weinstein Wisdom included doing things because they were the right thing to do, and though I only figured it out later, that doesn’t require empathy. There was never really a situation where I required empathy from him until my mother died, and we all went our separate ways at that point. I was surprised that he did nothing to help me when I moved out of our family house and into my first apartment. The closeness we had shared seemed to disappear.

The dividing line in our relationship came when I was 23. I called him at 4:00 a.m. from a hotel lobby to report the disastrous situation I was in after flying glass and debris from a gas explosion in the building next to mine had demolished my apartment. I feared I might be without a home to return to. His response was, “OK,” and he hung up. I was stunned. After that, I limited my time with both him and Barbara.

As my brother came to the same realization about our father’s lack of empathy, we started referring to him as, “The Man From the Planet Feelnot.” His emotional dials appeared to be calibrated differently than most people’s. His positive emotions were always turned up to full blast, while his negative emotions were so low they barely produced a blip. When I confronted him about not being present for me after the gas explosion, he said, “In business, I always know what my customers want, but I often don’t know what those closest to me want. I consider it a personal failing.” I was surprised that he realized he was missing something important when it came to emotions and our relationship and that he admitted to its being a problem. He seemed baffled that he couldn’t fix it.

A Black Hole

After the murder, my father was released on bail, and we met at his lawyer’s office. He told me exactly what happened, speaking about it emotionlessly. He seemed completely unaffected by his violent outburst. He was delighted to see me, but not upset about what had happened. When we left the lawyer’s office and went back to his apartment, the scene of the murder, he behaved as though nothing unspeakable had occurred there. The lawyer cut through the webs of crime scene tape, and my father walked right in, unfazed. My brother, the lawyer, and I hesitantly crept in behind him, afraid of what we might see.

It became glaringly clear that my father was not behaving in anything resembling a typical way for the circumstances. He didn’t talk about his wife—he was more concerned with the damage the police did while searching his study. He wasn’t asking himself the myriad questions one might assume he would have: How could I have killed my wife? What is going to happen to me now? Will I be in prison for the rest of my life? No, none of that. It was indescribably creepy. He seemed like a happy robot that blew a fuse and was stuck on a comfortable setting. He was acting so obviously inappropriately that his lawyers ordered a full psychological and neurological workup on him. The assessment revealed what I never could have guessed: a large cyst on his brain.

At first, I was suspicious that this might be a ploy by my father’s top-notch legal team to invent a decent defense. I learned it was very real when my brother and I accompanied my father to his neurologist. We were told that the cyst could affect his behavior in unpredictable ways, but removing it at his age, 65, would likely kill him on the operating table. If he lived (which wasn’t likely), he could be severely mentally damaged. I didn’t see his brain scans at that visit, but I wish I had. I imagined a “very large” brain cyst to be about the size of a walnut—not an orange, as was actually the case. Removing it was not a viable option.

While out on bail for two years, my father continued to behave as though nothing of major significance had happened, and his future would take care of itself—no need to worry. He was not depressed or scared in the least. In fact, he met and married another woman while he was awaiting trial. My brain was bending into origami shapes, trying to understand how he could behave this way, cyst or not. After all the legal wrangling, he accepted a plea deal—a reduced sentence due to the cyst and the neurologist’s report—that put him in prison for 14 years. While there, he never once complained. He sounded happy and upbeat on the phone, the same as always.

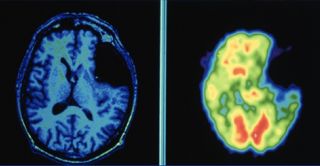

Eventually, I associated his evergreen great mood with his brain cyst, though I didn’t know exactly how that was possible. I wanted to understand how he could be wonderful in some ways, yet lack empathy and normal emotions. I dug in. Brains and behavior became my obsession. My research led me to believe his “brain defense,” as some experts referred to it. About 20 years after the murder, I googled my father’s name. The results that came up shocked me. I saw his brain scans for the first time—one black and white MRI and a colorful PET scan. Almost a quarter of his brain appeared to be a black hole in both images. Had I seen these scans back when we were in the neurologist’s offices many years prior, I would not have had the questions that plagued me for so long. I would have thought, “How could anyone with a brain like that not behave abnormally?” These images redefined my relationship with my father. They made the incomprehensible understandable.

Beyond transforming my understanding of my father, they also transformed the criminal justice system. Brain scans had never been permitted in the guilt-innocence phase of a criminal trial before. My father’s lawyers had to fight to get them in, which they did, and that set an important new precedent. It gave birth to what is now known as neurolaw. Countless articles, books, and lectures have been devoted to my father’s case.

A few years after discovering the brain scans, I came into possession of the neurologist’s report. The neurology team extensively documented the specifics of his brain (such as pressure on his frontal and temporal lobes), how he could be expected to behave, and the precise ways that what happened in the apartment on that horrible day could be explained. My father didn’t have a “personal failing” regarding empathy; he was literally not able to feel empathy, anxiety, and negative emotions. I could finally forgive him, and in my heart he went back to being the father I loved so dearly.

There are people, even today, who do not believe his cyst affected his behavior. Most of them have never met him or seen his brain scans and the neurologist’s report, but some of them have. I used to get frustrated by people like this because I believe the neurological facts speak for themselves. Fortunately, one of the things my father taught me has helped relieve that distress: “You know the truth, and I know the truth. That’s all that matters.”

Joni West is the author of Full Frontal Murder Memoir: A Daughter Reveals the True Story Behind the Shocking Crime That Went From Tabloid to Textbook and Will Change the Way You See Blame and Brains.