10 Ways You're Stronger Than You Think

Within each of us are powers and abilities we underestimate, but which can carry us through many challenges. You’re stronger than you think.

By Psychology Today Contributors published March 8, 2022 - last reviewed on October 25, 2022

1. Imperfection

Invulnerability is a classic superpower, but in real life pretending to have it tends to backfire. Instead, those who make mistakes, and let others know it, are better liked and often more successful.

By Marina Harris, Ph.D.

Connection has always been a basic human need. To achieve it, many people assume they need to put their best self forward, never make mistakes or blunders, and always know the right thing to say. This pressure can lead to stress as people second-guess their presentation, their actions, and their words. Research, however, suggests that such effort may not be worth it.

In classic studies on what came to be called the “pratfall effect,” social psychologist Elliot Aronson showed that people who demonstrated high levels of skill in trivia challenges but also committed minor blunders—say, spilling coffee on themselves—were rated more likable by others than similarly skilled people who made no such stumbles.

This research shows that it’s not only OK to be fallible, it can actually benefit us. Perfection is not something that other people find endearing. Being vulnerable is: When we see that others have flaws, we feel that we understand them better and can connect with them.

In your own life, this and other research suggests, it’s important not to get wrapped up in what you think will make you likable—because you’re probably wrong about it. Sometimes, in fact, the things we dislike the most about ourselves are the most endearing to others. (It works both ways: Sometimes what we like about ourselves isn’t necessarily a quality others appreciate.) Instead of acting in a way that you think increases your appeal, drop the armor, be your genuine self, and let people discover what they like most about you.

Marina Harris, Ph.D., is a specialist in eating disorders, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, sport psychology, mindfulness, and trauma-informed care.

2. Generativity

We often imagine that putting others before ourselves is a sign of weakness, but research suggests it’s actually a stealth superpower: The most “generative” people have better long-term well-being than others.

By Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D.

It’s often thought that feeling good about yourself derives from being able to look back with pride on your accomplishments, no matter how modest or grand. This focus on individual happiness is often referred to as “eudaimonic” well-being. But there’s another type of well-being that may be more important: Generativity, based on the belief that it’s important to care for others, specifically the next generation. People high in this trait are able to put themselves second, and research suggests that it is this cohort who feel more profoundly fulfilled as they progress through life.

In a recent study of generativity and well-being, our research team studied 271 participants in the Rochester Adult Longitudinal Study (RALS) across a 12-year period, from 2000 to 2012. The findings supported our prediction that people who became more generative over time also grew in their sense of personal fulfillment. Those who didn’t, on the other hand, had a declining sense of overall well-being.

If your well-being hinges on your sense of generativity, what can you do to enhance it? By definition, when you are highly generative, you care for the next generation. But need those you care for always be younger than you? Couldn’t you express your desire to care for people of your own generation? What about caring for people older than you?

The benefit derived from putting other people before yourself counters the idea that well-being can come only from that eudaimonic feeling of achieving your own personal goals. Erik Erikson, who first proposed the theory, called the opposite of generativity “stagnation.” In his model, people who stagnate become more and more self-focused, spending money on endless home redecoration, expensive vacations, and beauty treatments. It may seem counterintuitive that the best way to feel good is not even to think about how good you feel, but our study suggests that it lies in a very different type of pursuit.

Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D., is a professor emerita of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her latest book is The Search for Fulfillment.

3. Routine

Sticking to a daily routine can be viewed as rigid and unimaginative. To the contrary, research suggests that routine frees us from overthinking, improves mental health, and can, in fact, foster creativity.

By Steve Alexander, Jr., M.A., Ed.M., ARM, LMHC

Many people ignore the real successes in their lives and put themselves down for being, as they perceive it, unproductive, unmotivated, and unaccomplished. After multiple sessions of hearing my client Mike berate himself this way, I tried to be relatable: “Sometimes I also feel lazy and unmotivated,” I told him, but added that I was still usually able to get things done.

Motivation can be a powerful driver, but it is also fleeting and unreliable. Just consider the last time you felt motivated and how long it lasted. The truth is that it is more useful to have daily routines in place to help us achieve our goals. Imagine a heart surgeon who told you, “I can operate well—when I feel motivated.” You would not risk your health on the hope that this doctor felt motivated on the day of your procedure. Better to have your surgery done by someone who has routines in place that ensure her success regardless of how she feels.

Two recent studies tie both primary routines (hygiene, sleep, eating) and secondary routines (social activities, work) to better mental health. Studies of both athletes and nonathletes have found that routines benefit performance by reducing overthinking, which tends to foster stress and pressure. And research on rituals, or regular sets of actions that we do consistently, finds that they mitigate against stress and anxiety because they foster a sense of control. Observe some of the most successful people you know, however you define it, and you will probably notice strong daily routines that result in positive outcomes over time—and more robust mental health as well.

Steve Alexander, Jr., M.A., Ed.M., is a Licensed Mental Health Counselor in New York who has worked in multiple outpatient clinics, psychiatric settings, and is currently in private practice.

4. Persuasion

We assume we don’t have much influence over others, even those closest to us, but studies show we’re more powerful than we think.

By Vanessa Bohns, Ph.D.

When you want to convince another person to do something, the first factor you probably consider is how likely they are to agree. Such thinking can discourage you from attempting to influence them at all, and that would be a mistake because research shows your sphere of influence may be much larger than you imagine. No matter whom you’re trying to convince, you’re probably more persuasive than you believe.

For example, we generally feel more comfortable asking a friend rather than a stranger to, say, sponsor us in a charitable fundraising effort or help us with a task. But recent research by two colleagues and me found that while we tend to think our friends will be more amenable to our requests, strangers are almost equally willing to pitch in.

We asked participants to approach both strangers and people they knew well with a simple request for a favor: to complete a brief survey. Before making their requests, we asked participants how many people they thought they would need to ask before three complied. Participants who had been instructed to approach friends thought they would need to ask an average of 3.9 before three agreed, and those who had been asked to approach strangers thought, on average, that they would need to ask 9.4.

It turned out the task was easier than either group expected: Participants had to ask, on average, only 3.8 strangers or 3.1 friends to get three to consent. Not only did participants greatly underestimate their ability to get strangers to agree to their request, but, surprisingly, strangers were almost as likely as friends to say yes.

A growing body of research has found that not only do we have bigger social networks than we think, and are more central to those networks than we realize, but we also have more influence over more types of people. This all suggests that when you have something to ask or say, people may very well be willing to listen to you.

Vanessa Bohns, Ph.D., is a professor of organizational behavior at Cornell University and the author of the book You Have More Influence Than You Think.

5. Satisfaction

The ability to be happy with who you are, where you are, and what you have is a power that those who are never satisfied may want to emulate.

By Lawrence Samuel, Ph.D.

I have a friend who might be considered by many to be unsuccessful. A young adult, her professional and personal lives have not yet taken off, and while she’s keenly aware of this, she’s not especially bothered by it. By a different set of measures, though, I would say she’s very successful. She’s intelligent and funny and is known as a kind and generous person. She cares for her mother, with whom she lives, and walks dogs and babysits to earn money. She can’t afford luxuries, but she’s well liked, spends her time as she wishes—and she’s happy.

Our classic narratives of success are heavily defined by achievement, acquisitions, and upward mobility. Those who don’t subscribe to these narratives are often cast as “losers.” Yet a body of research shows that the so-called winners are no happier. In fact, according to several studies, outer-directed measures of success are actually less correlated with contentment and life satisfaction than inner-directed ones.

I propose an alternative narrative of success that is more likely to lead to happiness than the one we have been taught to embrace. Those who prioritize inner-directed success know this path. They avoid comparisons to others, knowing that stacking your achievements, no matter how significant, against those of everyone else is an unwinnable proposition. They have a holistic view of themselves, taking their self-worth from a consideration of themselves as complete, unique individuals, and knowing that no one can be more successful at being you than you. They celebrate their victories, no matter how big or small, and accept failures, learning lessons and moving on. And they prioritize relationships, inherently knowing that humans are social organisms and that success can and should be defined by how we relate to others and, ideally, improve their lives.

Lawrence R. Samuel, Ph.D., is an American cultural historian who holds a Ph.D. in American Studies and was a Smithsonian Institution Fellow.

6. Nostalgia

Letting our minds wander to the past can be guilt-inducing, but it shouldn’t be: Fond, nostalgic memories can boost our mood and make us feel whole.

by Matt Johnson, Ph.D.

With the challenges of the present moment and an uncertain future ahead, the past has never looked better. However, indulging a fondness for the past runs counter to popular advice. We’re routinely admonished not to “live in the past.” But is escaping into the past really such a bad thing, especially now?

When our minds wander back to a previous time, we don’t remember things exactly as they happened. Memory is our brain’s attempt at connecting us with the past—attempt being the key word. We don’t go through life with a Record button on, and when we conjure up a memory, we’re not hitting Replay. Memory is a highly inaccurate reconstruction of our past, painted with a broad brush that tends to gloss over many negative details. That’s why nostalgia can often deliver a warm feeling.

Engaging in nostalgia isn’t just comforting, though. Consider that who we were in the past isn’t who we are now: We may think, feel, or act differently today. As T. S. Eliot described it, “You are not the same people who left that station/Or who will arrive at any terminus.” Your memory works to stitch you together as a consistent, coherent person. When this process breaks down, you can feel a sense of discontinuity, which is linked to lower life satisfaction. Research has found, though, that people who frequently nostalgize have a greater sense of self-continuity, and a stronger sense of meaning in life. Looking back helps us make sense of where we’ve been and how we got to where we are. It helps us tell a meaningful story of our life and of how all of our discrete experiences fit together in a coherent narrative.

Engaging in nostalgia also appears to have some direct mental health benefits, such as reducing cortisol levels associated with the body’s acute stress response. Further, research suggests that a tendency to nostalgize can be a protective factor against depression and anxiety. One study found that recalling specific positive life experiences was especially valuable for individuals who had experienced early-life trauma.

Nostalgia, then, can carry immense benefits. As Gabriel Garcia Marquez put it, “No matter what, nobody can take away the dances you’ve already had.” Today, such memories may be more important than ever.

Matt Johnson, Ph.D., is a professor at Hult International Business School in San Francisco, California and the author of Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes our Brains.

7. Desire

Few feelings are more guilt-inducing than (or as irresistible as) a crush on someone who’s not your partner. But, in fact, research shows that outside crushes (as long as they’re not acted on) generally have a positive effect on people’s primary relationship.

By David Ludden, Ph.D.

Fiona is happily married to Garrett. She enjoys the time she spends with him and looks forward to a long and fulfilling life together. Yet, she can’t stop thinking about her coworker Brendan. She flirts with him a little at the office, and one night she even imagined she was making love to him while she was having sex with Garrett. It made the sex more exciting, even though she felt guilty about it afterward. She would never think of sharing these feelings with Brendan, though, nor does she have any intention of telling her husband about them.

Research confirms that crushes aren’t just for adolescents. Adults of any age can have them, even when they’re happy with their current partner. In fact, recent research found that people in committed relationships reported far more crushes than singles, perhaps because singles are more likely to act on their attractions to others rather than letting their feelings linger unrequited.

Another surprising research finding: People in relationships report mostly positive outcomes from their crushes. Their infatuation gave them something to fantasize about, brightening their day and bringing excitement into their lives. Some even found that having a crush strengthened their relationship—their romantic fantasies made them feel sexy, and they believed that heightened arousal improved the sexual experience for both themselves and their partners.

So why do adults have crushes anyway? The researchers who led a recent study suggest two possibilities: First, feelings of attraction may simply be hardwired into our sexual makeup; they drive us toward potential mates. But sometimes we’re attracted to people we know we’ll never have a relationship with. The other, more intriguing possibility is that a crush provides a test of the strength of our current relationship. If we can keep the attraction as a private experience, we know our commitment to our partner is strong. On the other hand, if we find ourselves acting on our desire by revealing our feelings to a crush, that’s a sign of real trouble in our primary relationship.

Instead of feeling guilty about crushes, perhaps we should understand that they can show us just how committed we are to our partner. If we weren’t, we’d pursue that other person rather than keeping our desires at the level of fantasy.

David Ludden, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Georgia Gwinnett College.

8. Hope

The power to access the belief that things can get better, no matter the challenges, can quite literally change the world.

By David Feldman, Ph.D.

Few people would use the word “hopeful” to describe the state of our world today, but we also know that hope can exist even in the midst of pain. Essayist and activist Rebecca Solnit wrote, “Your opponents would love you to believe that it’s hopeless, that you have no power, that there’s no reason to act, that you can’t win. Hope is a gift you don’t have to surrender, a power you don’t have to throw away.”

Real hope is no delusion. It isn’t about living in a fantasy world, and it doesn’t deny suffering and pain. In our book, Supersurvivors, my co-author and I profiled survivors of trauma who went on to do things that made the world a better place. A through line in their stories was what we called “grounded hope.” Even though all of them exemplified a forward-looking spirit, they were firmly grounded in the realities of their situation. When James Cameron, the only survivor of a 1930 lynch mob, established the first NAACP chapter in Anderson, Indiana, and ultimately founded America’s Black Holocaust Museum, he wasn’t under any illusion that the world was a wonderful place. His hope was fueled by a belief that, despite the resistance he would face, his hard work could help build a better life for Black Americans.

At its heart, hope is a perception—but one that gives us the power to create reality. It’s a perception of something that does not yet exist. And research shows that when people have hope, their goals are actually more likely to become reality. That’s because when people have a clear belief about what is possible, they’re more likely to take steps to make it happen.

You may have heard the expression, “Hope is not a strategy.” Don’t believe it: Hope is a way of thinking that pushes us to take action. Research by C. R. Snyder found that most hopeful people had three things in common: goals, pathways (strategies), and agency. They were under no illusions that all their strategies would work; they tended to try multiple pathways, realizing that many would be blocked. But they persisted because they had an abiding belief in themselves and their capabilities.

It’s tempting to lose hope today, but that would be surrendering a vital power.

David B. Feldman, Ph.D., is a professor in the department of counseling psychology at Santa Clara University.

9. Daydreaming

Far from a form of procrastination, an indulgence in fantasy, or a sign of an idle mind, daydreaming has been shown to deliver real-world benefits.

By Brendan Kelly, MD, Ph.D.

There are probably times during the day when your mind wanders and spends a few minutes imagining things you know are not real. Should that worry you? There is some evidence that mind-wandering hinders reading comprehension and performance on aptitude tests. Such consequences, however, must be weighed against growing evidence that mind-wandering also significantly benefits core psychological and emotional processes like autobiographical planning and creative problem-solving. It seems that most of us are fully aware that we concentrate less when we daydream but that this is a price we’re willing to pay.

In a situation where I don’t need to concentrate, I am happy to let my attention drift. I might even enjoy a mildly subversive thrill as my thoughts flutter away. We plan our life in daydreams, and while the future we imagine might be overly optimistic, the practice is still productive and forward-looking. Even better, by releasing us from the pesky constraints of reality, daydreams allow us to think more creatively about the problems of today and the possibilities of tomorrow. This facilitates imagination, problem-solving, and the ability to reach conclusions our rational minds might never permit if we were concentrating fully. Brain-scan studies have found that, contrary to expectations, our brains are more active when our minds wander than when we are focused on routine tasks. It had previously been thought that the only part of the brain active during daydreams was the “default network,” which is associated with low-level, routine mental activity. This research, however, revealed that the brain’s “executive network,” concerned with complex, high-level problem-solving, is also activated when we daydream. Far from idle, then, our minds are actually hyper-active when they drift away.

Such findings suggest increasing the value we place on daydreaming. We might lose focus on the task we set out to do, but that may just be the brain’s way of telling us it has more important things to think about: relationships, goals, or valuable general reflection. We could even benefit by consciously carving out some time and space to allow our mind to wander and see where it takes us

Brendan Kelly, M.D., Ph.D., is Professor of Psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, Consultant Psychiatrist at Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, and author of The Science of Happiness.

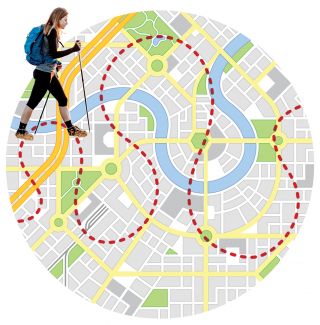

10. Restlessness

When boredom sets in, staying in one place can be bad for our mental health. Those with an urge to get out and enjoy new and different experiences may have a distinct advantage.

By Jutta Joormann, Ph.D., with Adam Zhang

One of the hardest things about the Covid-19 pandemic is that it has limited our ability to pursue new experiences. The loss of engagement in our usual environments can undoubtedly endanger mental health, but those who have been able to immerse themselves in new hobbies, goals, or even walking routes have found the activities to be beneficial and refreshing.

Research shows that experiential diversity—going to new (or at least different) places and engaging in different experiences—can improve well-being. This principle is intuitive: Most of us would agree that going on vacation, or just finding different activities to do every day, makes us happier.

For a recent study, a team tracked the location of participants for three to four months via GPS coordinates to examine whether daily movement could serve as an accurate assessment of the link between experiential diversity and positive affect. Participants regularly checked in via their phones to report their positive or negative emotions. Geolocation scores were determined each day based on the number of places a participant visited and the amount of time spent there. At the end of the tracking, some participants took part in MRI scans to examine brain activity.

As expected, positive emotions were higher on days when a participant’s geolocation score was greater, suggesting that daily novelty exposure is associated with well-being. The team also found that experiential diversity was associated not only with more positive emotions but also with more novel and diverse experiences the next day. In other words, it created a positive feedback loop, or “upward spiral,” that promoted further positive emotions. The MRI scans found that the degree to which the neural regions important for memory and processing of reward/environmental novelty work together is associated with the relationship between experiential diversity and positive emotions.

Those who can engage in new and diverse experiences may enjoy lasting benefits. Devoting time to such activities, especially in different places, may deliver a significant upward spiral of good feeling.

Jutta Joormann, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Yale University who studies risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders. Adam Zhang is a Yale undergraduate.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: insta_photos/Shutterstock