Why Would Anyone Aid and Abet a Predator?

For every predator, there's an enabler—sometimes an entire network. Inside the mind of an enabler.

By Jennifer Latson published December 20, 2019 - last reviewed on December 21, 2020

Nxivm leader Keith Raniere was convicted last year of sex trafficking, forced labor, and racketeering in connection with the so-called self-help group that former members say he ran as a cult. But he didn’t run it alone: His second-in-command, Nancy Salzman, helped enlist members—then worked to undermine those who attempted to expose Raniere’s crimes. Salzman had so much faith in the group’s mission of personal growth that she even recruited her own daughter, now 42, who became a sex slave to Raniere.

Last March, Salzman pleaded guilty to hacking into the email accounts of “enemies of Nxivm” who were planning a lawsuit against the group. She told the judge she had set out to be a force for good. Somewhere along the way, she’d gone wrong. “I believed that we would be helping people,” Salzman said in court. “I compromised my principles.” Former Nxivm members, including Salzman’s daughter Lauren, testified that Raniere exploited people financially and sexually. Women who joined a secret sect within the group were branded with a tattoo of Raniere’s initials and coerced into having sex with him and each other as “masters” and “slaves” but forbidden from having relationships with other men. Those who broke Raniere’s rules were punished harshly. One woman was locked in a room for nearly two years after becoming romantically involved with another man.

Why would anyone form an alliance with Raniere—especially someone as well-educated and seemingly empathetic as Salzman, a former psychiatric nurse? It’s the same question we ask of those who play a supporting role to sexual abusers like Jeffrey Epstein and fraudsters like Bernie Madoff. What kind of person would stand idly by in such cases, or worse, actively assist?

Enabling is more common than you might think. For every predator, there’s an enabler—sometimes an entire network of enablers—and they’re not inherently malevolent or unscrupulous. Under the right (or wrong) circumstances, psychologists say, many of us would likely do the same.

“It’s very hard not to be an enabler,” says Elinor Greenberg, a psychotherapist and the author of Borderline, Narcissistic, and Schizoid Adaptations. “You don’t have to be a terrible human being, in the beginning, to do this. Although some enablers are terrible human beings who take delight in ruining other people’s lives, most aren’t evil. They’re just not heroic.”

Some people are more likely to go along with predatory behavior than are others, either because they’re especially vulnerable and lack the courage to voice their objections or because they’re well on their way to becoming a predator themselves and have no objections. In most cases, though, it comes down to trusting the wrong person. And it’s a matter of pacing: Master manipulators can push the ethical boundaries so gradually that their targets don’t even notice what is happening until one day they’ve gone well over the line—and likely dragged others across with them.

Over the Line

Liane Leedom, a psychiatrist and professor at the University of Bridgeport, studies the personality disorders that lead people to manipulate others—and how to lessen the damage they inflict, a topic of intense personal interest. In 2003, her husband at the time was arrested on charges of impersonating a doctor and sexually assaulting patients at the couple’s addiction treatment center, where he was the business manager.

Learning that he’d harmed her patients was hard enough; knowing she’d unwittingly enabled the abuse was even harder. Although she hadn’t known about the assaults, she’d heard him tell people he was a retired doctor, she says. She’d chalked it up to his “entertaining storytelling.”

The revelation was devastating, personally and professionally. But it also gave her a new calling: to stop others from being deceived by psychopathic people and to help prevent the children of psychopathic parents from being abused or developing similar traits themselves.

Talking to people who have been victimized in similar ways, she’s heard echoes of her own experience, starting with a manipulator who wins you over with promises—then preys on your fears.

“One thing these people do is find out what other people are afraid of, and they generate an atmosphere of fear and mistrust. Then they portray themselves as the one person who’s safe,” Leedom says. “They also exploit moments of high emotional arousal. People stop being fully rational when their emotional arousal is high—when they’re fearful or elated. When someone says, ‘Just do what I say and all your dreams will come true,’ your logical, reasoning brain doesn’t fully engage.”

Opening an addiction treatment clinic had been Leedom’s dream, and after her husband helped make it a reality, it was hard for her to closely examine behavior of his that made her uneasy, including his habit of telling tall tales. Citing research on those who consider themselves victims of highly psychopathic people, she reports that pathological lying is the one symptom that’s found in nearly 100 percent of the cases.

Enablers are “marks” or targets of manipulators every bit as much as are those who are more overtly, often criminally, victimized. Machiavellian manipulators use the same techniques to trick enablers into helping. Often, it’s the promise of some reward: money, power, love, or even spiritual enlightenment. “It has to be so valuable that they’re willing to overlook the growing discomfort they feel as the relationship, and their role in it, changes,” Dale Hartley, a psychologist and the author of Machiavellians: Gulling the Rubes, explains. But it changes so incrementally that they never quite notice the transformation.

The Idiosyncrasy Credit

Master manipulators have a knack for finding their victims. In some cases, that means people who have already been conditioned not to voice their concerns—or even their opinions, according to Greenberg.

“People who really don’t know who they are, who depend on other people’s approval, are vulnerable to being taken advantage of,” Greenberg says. “A lot of people I see in my practice were neglected or abused as children, and under those circumstances they don’t do a lot of self-development, they grow up without a firm identity. They’re really easy to manipulate because they’re passive and they don’t have strong views on anything.”

Famous, wealthy, and powerful predators—those who move in elite social circles à la Jeffrey Epstein—have frequent access to another species of enabler: the narcissist. Because narcissists have little emotional empathy and a high regard for social status, they’re able to rationalize abusing someone lower on the social hierarchy to win the favor of someone near the top.

As Greenberg explains, a narcissist could procure underage girls for Epstein and justify it by thinking: The girls are dirt. They’re nothing. And they get to meet famous people and go on a great vacation. What’s so bad about it?

Status alone can be enough to attract a legion of enablers—not all of them narcissists. That was true for British entertainer Jimmy Savile, the popular host of the BBC’s Top of the Pops and Jim’ll Fix It who was at one time a friend and informal advisor to Prince Charles. Although there were whispers during Savile’s lifetime that he might be a pedophile, it wasn’t until after his 2011 death that a National Health Service investigation revealed the staggering extent of his crimes: He’d raped or sexually assaulted at least 500 children, some as young as 2.

When it came to what some psychologists call the “dark triad” of personality traits, Savile had them all: narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism, according to the psychologist and journalist Oliver James. And while Savile demonstrated a predator’s uncanny

knack for sensing vulnerability in his victims, it was his celebrity that empowered him to abuse the children without consequence, says Ian Robertson, an emeritus psychology professor at Trinity College in Dublin. Savile was such a prolific predator that it was impossible no one else knew; several victims said they had attempted to report the abuse, only to be ignored. Savile’s celebrity created a protective forcefield around him, Robertson says.

On a practical level, Savile’s status afforded him powerful lawyers and friends in high places who could ruin the life of anyone who dared to blow the whistle on his behavior. But the halo effect of his fame worked in more subtle ways as well.

Savile’s iconic status, coupled with his reputation for doing good, gave him seemingly unlimited amounts of what Robertson calls “idiosyncrasy credit”—a term coined by CUNY Baruch psychologist Edwin Hollander, meaning that the higher your value in your social group, the more you are allowed to deviate from its norms without being ostracized. The more social credit you have, the more you can withdraw in the form of tolerance for your “idiosyncrasies.”

“Such withdrawals do deplete your banked credit, but if you are a credit billionaire, as Savile was in British eyes, then you can make an awful lot of idiosyncrasy credit withdrawals before they show up on your balance sheet,” Robertson says.

Predatory Push

Narcissistic enablers tend to care more about a predator’s status than a victim’s suffering, but most take no particular pleasure in others’ pain. Another type of enabler does. These harbor their own predatory impulses, but have the moral awareness—or fear of repercussions—to restrain themsleves, Greenberg explains. That is, until they meet a more brazen ringleader.

“Think about the bullies in high school, before they develop into better people, as many do. Some never grow out of it. They just like hurting people,” Greenberg says. “If someone in power gives them permission to do that, or a rationale for it, that’s the push they need to act it out.”

Take Myra Hindley, who helped British serial killer Ian Brady murder five children in the 1960s. By most accounts, Hindley was a sensitive, law-abiding 18-year-old when she met Brady, who was four years older. He, on the other hand, had a history of torturing animals and other disturbing childhood behavior.

It was plausible that Brady had forcefully persuaded a reluctant Hindley to go along with the rape and murder of three boys and two girls, either because she was afraid he’d kill her or because she was so in love with him that she was willing to do whatever he demanded—both of which she later claimed in her requests for parole, according to Tom Clark, a sociologist at the University of Sheffield.

Clark, who has studied Hindley’s prison files extensively, says that although she appears to have gone from being a model citizen before meeting Brady to being a model prisoner afterwards, it’s impossible to absolve her of agency in the crimes. Hindley initially insisted she’d played no part in the murders themselves and had acted only as a lookout while Brady carried out the killings. But an audio recording the pair made of 10-year-old Lesley Ann Downey’s murder demonstrated otherwise. “She’s an assertive woman, with a sense of entitlement and even arrogance,” Clark says. “I can’t imagine her going along with something she didn’t want to do.”

Forensic psychologist Joni Johnston, who has researched the dynamics between partners who commit murder, also questions Hindley’s innocence. “Myra Hindley is a good example of a mousy, unexceptional women whose odds of becoming a homicidal maniac were remarkably slim before she met Ian Brady,” Johnston says. “Yet she herself admitted that, even though she knew right from wrong and had never had any violent urges of her own, she not only became a willing accomplice but ultimately took personal pleasure in the murders she and Ian committed.”

Under the Influence

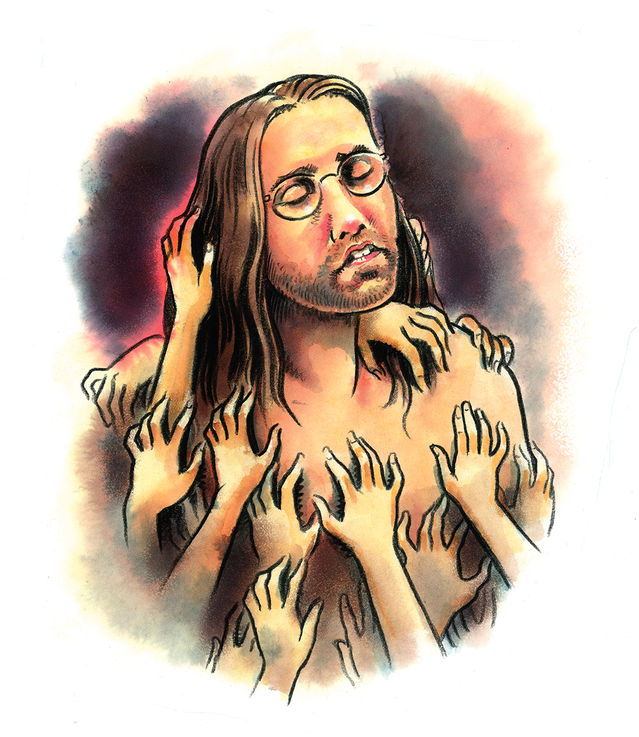

Steven Hassan has never met Nancy Salzman, but he can understand what made her sacrifice her values to serve a corrupt cult leader. He did the same as a member of the Unification Church.

Hassan was 19 and studying poetry at Queens College in 1974 when three attractive, flirtacious women invited him to dinner to learn about their student movement. They turned out not to be students, and the movement was actually the cult led by Sun Myung Moon, a Korean billionaire who claimed to be the Messiah. Hassan, an honor student who considered himself an independent thinker, would not have believed he was at risk for being recruited into a cult. But within weeks, he dropped out of school, emptied his bank account, and turned his back on his family, his Jewish upbringing, and his values to join the Moonies.

“I came to believe the Messiah was on Earth, and I needed to follow him blindly,” says Hassan, who got out of the cult in 1976 and has worked since then as a counselor, helping others in similar situations. He’s the author of several books on cults, mind control, and manipulation, most recently The Cult of Trump.

The techniques—deception, flattery, trickery, and coercion—that cult leaders like Moon use to manipulate their followers are the same used by predators like Epstein, Hassan says, as well as by authoritarian political leaders, terrorist groups, and even the organizers of multilevel marketing schemes.

Flattery, praise, and an outpouring of love are typical hooks used to get people on board initially. Guilt, punishment, and the indoctrination of fear are introduced later to keep them from leaving. Cultivating fear, especially the fear of outsiders, is a nearly universal element of mind control, Hassan says. Cult leaders often instill irrational fears about what will happen if followers leave the group: Hassan, for example, was told he’d be possessed by Satan if he walked out. But sometimes the fears are entirely rational. Both Epstein and Raniere collected—and threatened to expose—incriminating information about their enablers.

While master manipulators like Epstein typically lure enablers with money and prestige, cult leaders often exploit more altruistic motives, promising that they can save the planet or achieve social justice. The promises are, of course, hollow, and as with other predators, cult leaders slowly ratchet up their demands over time, forcing their followers to adapt their thoughts and actions until they barely resemble the people they once were.

Members of the Peoples Temple, for example, believed that they could create a more equitable world by obeying Jim Jones. They didn’t question him when he told them that poisoning themselves, and their children, was part of that plan. Hassan would have done the same in 1974 if Moon had ordered it.

“I was trained to die or kill on command. When I saw images of the bodies in Jonestown, I thought, I would have drunk the punch if I’d been told to do that,” he says. “Even though it’s horrible, I was that far under their influence and out of touch with my own values and belief system.”

Hassan doesn’t hold Salzman or the other members of Nxivm fully accountable for what they did while under Raniere’s influence. “These seconds-in-command are often victims who become victimizers because they want to please the leader. I don’t think they’re necessarily evil people,” he says. “I think it really depends on what has been done to them.”

Cult members who would sacrifice anything for their leader aren’t suffering from Stockholm syndrome, because that implies they’ve been forcibly held captive—and even then, it’s extremely rare, Hassan says. The term was coined after a 1973 bank robbery in Stockholm, where hostages formed a close connection with their captors. Some even visited the bank robbers in prison afterward. “That’s not a normal reaction to being held prisoner,” Hassan says. “It’s more a form of trauma bonding. When our life is being threatened, there can be an unconscious adaptation to want the approval of the person threatening it, so much so that we think of them as good people.”

“What [the heiress] Patty Hearst experienced was more like brainwashing than what I experienced,” he says. “She was kidnapped by force and held captive in a closet. I met some women who flirted with me, and I went with them of my own accord. That method works much better in the long term. Once she was away from the cult and knew she wasn’t in danger, it was easier for the real Patty to come back.”

Because cult members believe they’ve chosen a path of their own free will, it makes it much harder for them to recognize that their personality has been essentially reprogrammed. But it makes it easier for others to see them as responsible for crimes they commit on behalf of a leader they chose to follow—and not someone who forced them into it at gunpoint.

The more serious the crime, the trickier the question of culpability. But the problem with mind control is that it doesn’t just shut off at a certain point—like when you’re ordered to kill. When your mind is truly under someone else’s control, you’re not aware of it. As a criminal defense, however, this raises the specter of Adolf Eichmann and his claim that he was only following orders when he helped orchestrate the Holocaust.

Political Predators

In Hassan’s view, when authoritarian leaders manipulate their citizens, entire countries can become cults, as Germany did under Hitler. And while historians have poked holes in Hannah Arendt’s argument that Eichmann himself had no particular contempt for the Jews he helped kill, it’s hard to believe that the millions of Germans who helped perpetuate the Nazis’ atrocities were all motivated by hatred. (Some people do, including political scientist Daniel Goldhagen, who made the case that they were “willing executioners” because of widespread, deeply rooted anti-Semitism.) Hassan, on the other hand, argues that while many ordinary Germans were anti-Semites, those who weren’t still cooperated because of two human tendencies: an impulse to conform and an innate deference to people in power.

Hitler employed the same manipulative techniques other cult leaders have used, starting with flattery and building to fear, Hassan says: “He was appealing to the Germans’ sense of nationalism. He promised to make Germany great again after WWI.”

And while a number of researchers have tried to pin down whether Hitler was a psychopath, a narcissist, or something else entirely, he certainly had a personality disorder, according to many experts, including the late Polish psychologist Andrzej Lobaczewski, who lived under both the Nazi and the Soviet occupations before emigrating to the United States in the late 1970s. He developed the term pathocracy to describe what happens when a predator with a personality disorder gains political power. In the case of Hitler, Stalin, and other authoritarian leaders, their disordered thinking can spread to the public at large, Lobaczewski argued.

“If an individual in a position of political power is a psychopath, he or she can create an epidemic of psychopathology in people who are not, essentially, psychopathic,” Lobaczewski wrote in his book Political Ponerology.

This theory helps explain why human history is riddled with atrocities, especially if you believe, as psychologist Steve Taylor of Leeds Beckett University does, that most of us recoil from the idea of committing them.

“This is not because all human beings are inherently brutal and cruel, but because a small number of people—that is, those with personality disorders—are brutal and cruel, intensely self-centered, and lacking in empathy,” Taylor says. “This small minority has always held power and managed to order or influence the majority to commit atrocities on their behalf.”

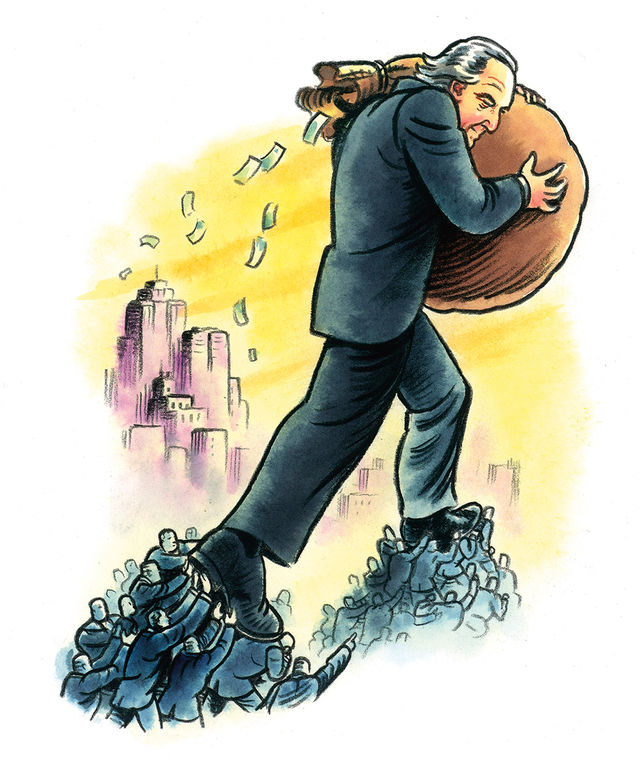

Psychopaths make up only about 1 percent of the general population, researchers estimate. But that number rises significantly in two demographics: within the prison population and among corporate and political leaders. Italian psychologists Floriana Irtelli and Enrico Vincenti estimate that between 4 percent and 10 percent of managers meet the criteria for psychopathy. According to Taylor, social scientists have found similarly robust narcissism among politicians and public figures.

The ruthlessness, sense of superiority, and craving for power that characterize both psychopaths and narcissists give them a competitive edge when it comes to vying for leadership roles. People with high levels of empathy, on the other hand, are less driven to seek those positions in the first place, Taylor says.

When pathological leaders do take over, the pathocracies they create typically become more entrenched and extreme over time, partly because “pathocrats” tend to attract others with similar disorders, who ride their coattails to gain power, Taylor says. Meanwhile, moral, fair-minded aides and advisers become increasingly ostracized and alienated. “The ‘adults in the room’ fall away, and the leaders are now surrounded by individuals who share their authoritarianism and lack of empathy and moral principles,” Taylor says. “They become surrounded by enablers.”

Gaining power in politics or any other field, brings out the worst in people with high levels of psychopathic traits. It reinforces their delusions of superiority and feeds their sense of entitlement, making them crueler and more remorseless. Being surrounded by sycophants further erodes any self-restraint they might have had, Taylor says. They become more unrestrained and more corrupt. “They become drunk with their own power.”

“Bad Samaritan” Laws and More Pushback

How can people avoid becoming enablers? First, we have to realize that most of us aren’t wired to whistle-blow—and that standing up to powerful predators is never easy, according to Hartley, the psychologist who studies Machiavellianism. “It would take guts to cross a predator like Epstein, for example. Once you’re knee-deep in it, he can’t let you go because you know too much,” he says. “Or, say you’re working with Madoff, and you have a crisis of conscience. Once you blow the whistle, you’ve lost your career; you’re going to be deposed and dragged into lawsuits. This is going to take over your life.”

Because it’s human nature to want to uphold the status quo, some say it may take systemic change to stop the epidemic of enabling. Zachary Kaufman, a law professor at the University of Houston, has advocated for new laws that are tough on people who are aware of abuses but say nothing. “The #MeToo movement has shown not only how rampant sexual abuse is, but also how often third parties disregard it—or even enable it,” Kaufman wrote in a 2018 op-ed for the Boston Globe. “At least 16 people admitted witnessing or knowing of Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse; his behavior was notorious within Miramax and the Weinstein company.” Others reportedly knew for years that USA Gymnastics physician Larry Nassar was assaulting young gymnasts and did nothing. The same goes for chef Mario Batali, comedian Louis C.K., and seemingly countless others. “If bystanders had acted instead as ‘upstanders,’ the assaults might have been prevented or stopped,” Kaufman says.

Laws that make it a legal duty to report such abuses would reinforce the collective sense that it’s also a moral obligation, Kaufman believes. They would help express a cultural “revulsion at silence, treating it as a type of complicity,” he says. While some states already have so-called “Bad Samaritan” laws targeting both passive bystanders and active enablers, they are inconsistently enforced, and most people don’t even know they exist. Making these laws more forceful, standardized, and widespread would help expose bad behavior. We also need to strengthen the laws protecting whistleblowers from retaliation, Kaufman argues—and to do a better job of listening to them.

Enablers need to understand the importance of speaking up, especially if their ordeal has lessened. More often, the opposite occurs: People are so eager to get a dangerous person out of their own life that they don’t tell the next potential victim that the person is a threat. Relatives are particularly prone to silence, out of a combination of shame and complacency, Leedom says, and in keeping quiet they perpetuate an endless cycle of abuse.

It will take systemic change as well to keep people with personality disorders from consolidating power in business and government, Taylor contends. On a practical level, he believes potential leaders should be evaluated for narcissistic and psychopathic traits, and that high levels of these traits should prevent someone from occupying the corner office—or the Oval Office.

On a philosophical level, he says, we need to recalibrate our social values to stop collectively enabling predatory leaders. People with the greatest empathy should be encouraged and incentivized to take on high-status roles.”

It’s impossible to teach empathy to people with strong psychopathic traits; keeping them out of power is the only real recourse we have, agrees Leedom. “We have to learn that we can’t put someone like this in charge—of a family, a church, a corporation, anything, ” she says. And we can warn potential enablers.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: Motortion Films/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Followtheflow/Shutterstock