Lust for Life

Those who crave risk or novelty respond to fear differently from others. They see stressors as challenges to master, not threats that can crush them.

By Kenneth Carter Ph.D. published October 15, 2019 - last reviewed on September 15, 2020

Cliff diving isn’t a typical activity for anyone, much less a person who is afraid of heights. But Mike, a 20-year-old living in Atlanta, does it as often as he can, despite the fear. He’s also skydived at least four times. The first time, he was a little disappointed. “I actually wasn’t scared at any point, which was weird.” The second time Mike told his guide, “The last guy failed to scare me, so I want you to scare me.” Even by his own reckoning, this isn’t something to say to a skydiving coach. “Beforehand, he told me that when they’ve got somebody who isn’t cooperating (apparently some people will grab the guide’s arms or what not when they should be pulling the chute), the guide spins them around really fast. Because this increases G-force, they pass out and the instructor can get them safely to the ground. We’re in the middle of free fall and that is basically what he does to me. He takes my hand and bends it down slightly, so I start spinning extraordinarily fast in one direction. Then he stops me, and I spin in the other direction extremely fast. Then the next direction extremely fast, and the next. My eyes were pretty much popping out of my head…eventually he pulls the chute, and before I knew it, we were just coasting again.”

His aeronautic feats don’t end with skydiving and cliff diving. He also hang glides. But “as far as complete and utter fear beforehand, I’ll give that to cliff diving. I’m scared of heights. Even if it’s only a 35-foot jump, it still gets the blood pumping. Each time, I think, Why am I up here? I am jumping from heights that I hate into the water, which is not my favorite.” (Mike is not a big swimmer.)

Mike is partial to spending his leisure time in activities that seem dangerous to the rest of us, like bull runs. The Pamplona run is the most famous. Originally, it served to move bulls from the fields to the bullrings for bullfights that accompanied festivals across Spain. It has become a worldwide phenomenon. “Once you’re in the actual run it’s a sort of out-of-body experience, but intensely adrenaline packed,” says Mike.

He has also tried zorbing—a sport in which you are strapped inside a capsule that is then placed inside a gigantic transparent ball. The ball is rolled along the ground or down hills. And Mike has eaten fugu (pufferfish)—although, disappointingly for him it was only the moderately poisonous type. Still on his To Do list: swimming with sharks, bungee jumping, and saving a human life.

Sophie Radcliffe quit her job running the commercial division at a major U.K. tech startup because she was ready to live her life guided by her personal mantra, “One life, live it!” In the last few years she’s completed an adventure race through the jungle of Borneo, cycled the 244 miles from London to Paris in 24 hours, and, in 2014, became the first (and so far only) person to cycle the Alps and climb the highest mountains in all eight alpine countries.

She says she enjoys her “pain cave.” “I love pushing myself physically and mentally. I love being in the pain cave because it’s there I find out the most interesting things about myself, and that helps me to learn and grow into the person and athlete I’d love to become.”

Sophie writes a fitness, lifestyle, and adventure blog encouraging others to “feel invincible” and recently moved from Great Britain to France to prepare for her next adventure. She cycles, climbs, runs, and travels. She tried skydiving but didn’t enjoy it because she says she’s not into high-adrenaline activities. For Sophie, the satisfaction comes from pushing herself to conquer challenges. She’s on a mission to inspire others to do the same.

Kirill Vselensky loves taking pictures, especially travel photos. He shoots landscapes, buildings, bridges, landmarks, nothing too unusual—except that his shots are captured from atop some of the world’s tallest buildings. Kirill loves to climb to the top of skyscrapers, bridges—anything climbable—and take pictures of himself dangling hundreds of feet above the ground, suspended without safety gear.

Known as the Russian Spider-Man, he is one of Russia’s extreme climbers, called roofers, who sneak their way to the tops of buildings and perform tricks like standing on one leg, balancing on the side of window ledges, teetering on the edge of roofs. His biggest fear? It’s not falling; it’s being detained by authorities.

Although he now has over 55,000 followers on Instagram, he was seeking out sights long before anyone was watching. “As a kid I used to love to visit people, as every time there was a new view from the window. It was an easy way to find adventure in your own city,” Vselensky explained to a newspaper reporter. Now what he sees is much more extreme. He started scaling buildings in 2008 because, he says, he “likes the views.” When he was asked what goes on inside his head, he replied, “Nothing special. I just try to think about hanging tight and staying alive.”

It may seem as if thrill seekers have a death wish. This is what Sigmund Freud might have believed. It’s also what I believed for a long time. In fact, it’s one of the reasons I’ve spent so much time reading about, researching, and interviewing thrill seekers around the world. I wondered what could drive a person to intentionally seek out activities that were so utterly intense, even chaotic. Why would they risk their life running with the bulls? Why would they hang from a building or quit a high-paying desk job to spend more time in their “pain cave”? What drives people to seek out the most dangerous, even outrageous, experiences they can find?

Sensation Seeking: The Science

To some extent, we all crave complex and new experiences—that is, we all seek new sensations. Whether it’s our attraction to the new burger place down the street, the latest shiny gadget, or the newest fashion trend, newness tugs at us. It’s simply human nature.

What sets the high sensation-seeking personality apart is that it craves exotic and intense experiences despite physical or social risk. Vselensky knows that hanging off buildings is risky. (Who doesn’t?) But he does it anyway. Is it because he’s seen people on TV, in the movies, and on YouTube do this stuff? That’s certainly part of it.

The extreme products, activities, and entities that have emerged in recent decades—Red Bull, X Games, the Extreme Sports Channel—are responding to our collective interest in thrill seeking as a spectacle if not a personal endeavor. And these extreme activities have spread quickly as early adopters—people with high sensation-seeking personalities—devoured them with gusto and shared their experiences enthusiastically online.

However, I don’t think TV and social media are currently inspiring more thrill seekers as much as such outlets are giving those who are already high sensation seekers permission or even new ways to indulge in their passions. Thrill seekers have been around a long time. From gladiator games in the ancient Roman arena to modern mud runs, humans have had a passion for thrills both as a pastime and as a spectator sport. And people have been trying to understand their appeal since the very birth of psychology.

Freud suggested that the id, source of the drives that keep us alive, also has an unconscious desire to be dead. Yet, when you actually talk to most thrill seekers, they don’t express a death wish at all. “What I have is a kind of addiction to life, for lack of a better word,” says Mike. “It’s not a disregard for life but an attempt to intensify moments instead of dull them out.” This is what I heard from people over and over again: High sensation seekers are more in love with life than any of us could imagine.

Today, one of the dominant perspectives in psychology is the Big Five theory of personality. It holds that we are all mosaics of five main personality traits: openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and extraversion.

Openness to experience is your willingness to try new things and your affection for the new. Conscientiousness is your ability to stick to the plan and act with integrity. People who score high on conscientiousness are seen as organized, reliable, and punctual. Agreeableness is how empathetic and interested in other people you are. Neuroticism describes how much you worry about things or get tied up in your own thoughts and feelings. Extraversion describes your energy focus; those who score high in extraversion are seen as social, active, and talkative.

But a love of thrills isn’t one of the Big Five, and it’s not reflected reliably by any combination of the factors. While some thrill seekers have some of the impulsivity of extraverts, many others don’t. Some are drawn to new things and might score high on openness to experience, but others repeat the same thrill-seeking experiences because they find something new in the activity every time.

Scientific research on sensation seeking didn’t begin until the late twentieth century, and it didn’t start in the base camps of Mount Everest. It began in a dark room filled with nothing—literally. Researchers weren’t trying to explain mountain climbing or bull running. They were trying to get to the bottom of mind control.

Shortly after the Korean War, Canadian psychologists, with funding by their government, began studying such brainwashing techniques as sensory deprivation. In his lab at McGill University, Marvin Zuckerman was intrigued by how people reacted to the loss of sensation. For the first hour or so, all of the research subjects simply sat in the nothingness. Then things changed. Some continued to sit quietly for hours. Others fidgeted, squirmed, and became bored and anxious, among other reactions.

Zuckerman speculated that some people (high sensation seekers) needed high amounts of stimulation and were irritated by sensory deprivation, while others (low sensation seekers) weren’t bothered by the lack of stimulation. Yet even though sensory deprivation theoretically irritated high sensation seekers, they were the very ones who signed up for the experiment in droves. Not only should they have found the study boring and frustrating, but they were also nonconformists, unlikely to be interested in a tedious scientific experiment.

Why would an experiment in dullness bring the hippies out of the woodwork (this was the 1960s)? The researchers were stumped. Apparently, information had circulated from some of the early participants: The sensory- deprivation experience could induce hallucinations. The newcomers came for the fireworks of the hallucinations, not for scientific advancement.

Zuckerman didn’t learn much about mind control with his experiments, but he learned a lot about sensation seeking, work that scientists continue to build on today. He realized that sensation seeking was not only a quest for external stimulation, as originally thought. Sensation can come from emotions, physical activities, clothes, food—even other people. He found that sensation seekers are sensitive to their experiences and actively pursue stimulation that maximizes them. Sensation seeking shapes the way people interact with others, the things they do for fun, the music they like, the jokes they make, and even the way they drive.

If you think of sensation seeking as a continuum, high sensation seekers are at one end, always hunting out new experiences, even if (and in some cases because) they come with risks. Low sensation seekers may actively avoid new experiences. Most people fall somewhere in the middle, searching out new experiences unless there’s something to lose by doing so.

Parsing Sensation Seeking

Zuckerman concluded that “sensation seeking is a personality trait defined by the search for experiences and feelings that are varied, novel, complex, and intense, and by the readiness to take physical, social, legal, and financial risks for the sake of such experiences.” He also found that the high sensation-seeking personality is complex, comprising four distinct components, each of which contributes to an individual’s unique way of seeking or avoiding sensations:

- thrill and adventure seeking: the quest for risk and danger;

- experience seeking: the love of variety in sensations of the mind and senses;

- disinhibition: the ability to be unrestrained; and

- boredom susceptibility: the dislike of repetition.

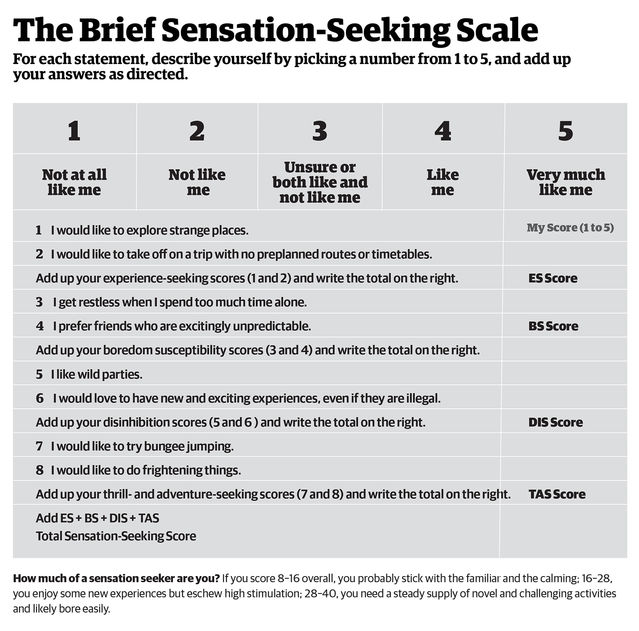

He also created a scale to assess how much of a sensation seeker someone is. It has been modified by others into a version called the Brief Sensation-Seeking Scale (BSSS). You can test how much and what kind of a sensation seeker you are.

When you think of sensation seeking, thrill and adventure seeking probably come to mind. This is the classic high sensation seeking trait. This component of sensation seeking emphasizes the enjoyment of at least moderately frightening activities. The secret in the sauce of thrill and adventure seeking is the potential for danger. Those with high thrill and adventure seeking personalities seek out physical activities that are exciting and risky. For some, the risk is not an essential component; it’s just the price of admission for the novelty that many with sensation-seeking personalities crave.

Both Mike and Kirill Vselensky fit this profile perfectly. They know the risks, but they do things like skydiving and hang gliding anyway. Mike, in particular, scores at the top of the chart for thrill and adventure seeking—a 10, the highest possible. For thrill and adventure seekers, risks may be ignored, tolerated, or minimized and may even be considered to add to the excitement of the activity.

Studies show that those with high sensation-seeking personalities experience increased release of dopamine during dangerous activities, which means they get more reward from thrill and adventure than do their lower sensation-seeking counterparts. In addition, high sensation seekers have lower amounts of norepinephrine and thus lower arousal systems; they show lower amounts of cortisol in response to stress. They actually feel less stress and more pleasure during risky and high sensation-producing activities.

In contrast, those who are not thrill and adventure seeking may avoid activities that seem risky or dangerous. Those activities can push them beyond their optimal level of arousal and create negative sensations.

Experience Seeking

Experience seeking is the quest for new experiences that challenge the mind and senses. Experience seekers look for a variety of experiences that are unique, rather than dangerous. These experiences may affect sensation seekers emotionally, intellectually, or interpersonally, through all five senses, including smell. Think of experience seeking as internal sensation seeking.

The important component in experience seeking is novelty, not danger. For some, the uncertainty of what’s to come brings anxiety and fear, and it activates the behavioral inhibition system. For the high sensation seeker, with a weaker inhibition system, novelty isn’t associated with anxiety; the weaker inhibition system means lower cortisol levels and a reduced stress response.

And because they have increased levels of dopamine, novel activities bring them greater pleasure. Those who are predisposed to be experience seekers are able to resist and minimize psychological and physical stress. When confronted with travel, new food, and other nondangerous options, the low levels of stress hormones and higher experience of pleasure make it easy for experience seekers to try new things.

A few years ago, heading to Hong Kong for a week, I received confirmation of a dinner reservation in a hard-to-book restaurant: “We will delight you with a six-course exotic meal. And we’ll present you with the menu at the end of the meal.”

The end of the meal? If you score high in experience seeking, that probably sounds kind of fun. If, like me, you score low in experience seeking, it’s likely that you want to know exactly what things are before you put them into your mouth.

Remember Sophie? While she scores low in thrill and adventure seeking—she wouldn’t go skydiving again—she scores high in experience seeking. “I love traveling; I love to meet new people; I love new experiences. The challenge is the quest to experience the unknown and to see where it takes me.”

Another aspect of experience seeking involves being around people who stimulate such experiences because they are unpredictable and different. Experience seekers are drawn to an anti-establishment personality type that rejects the norm.

Disinhibition

Disinhibition involves the ability to be spontaneous. It includes searching for opportunities to lose inhibitions. People with strong disinhibition tendencies act regardless of potential consequences, while people with low disinhibition tendencies control their behavior more carefully and think through more of the consequences. They look before they leap. People high in disinhibition just leap.

The higher your disinhibition score, the more spontaneous you are likely to be. It might not be surprising that such people are injury-prone and more likely to participate in such activities as the World Naked Bike Ride.

Disinhibition is related to the inability to hold back. What typically holds people back from doing something is the potential for punishment, or even the anxiety around imagined punishment.

I recently had lunch with a friend at a coffee shop. The two of us shared a booth. Between us was a sign that said “Booths Reserved for Parties of Three or More.” Having low disinhibition made it difficult for me to sit there. It was as if the words of the sign got larger every time I looked at it. I imagined confrontation with my server about my inability to read or my contribution to the demise of civilization.

My inhibition system dumped buckets of cortisol in preparation for an event that never occurred. In contrast, low levels of cortisol are associated with disinhibition. With a low inhibition system and relatively low levels of stress hormones, there is less holding back.

For Sophie, lover of challenges, scores for disinhibition are relatively high. One of her favorite things to do is “leave home with my bike, passport, and credit card, and go where the wind takes me.”

Rather than run the 2016 London Marathon in typical sports gear, Sophie decided to tell her story by painting her body with inspirational messages and even some of her fears (and a sprinkling of gems and glitter too). Her mother tried to talk her out of it, but she persisted. “There’s no point in going halfway in, to test the water to see what happens. It has to be all or nothing, and that’s the way I live.”

Lots of sensation seekers with high scores in disinhibition live life the same way. When they try a new food, they don’t take a nibble—they take the biggest bite possible.

The last component of sensation seeking is boredom susceptibility, which boils down to one’s ability to tolerate the absence of external stimuli. Those with high scores in boredom susceptibility dislike repetition, and they get irritated when nothing is going on. People with high boredom susceptibility also tire easily of predictable or boring people, and they get restless when things are the same.

People who are susceptible to boredom have a difficult time tolerating repetition and nonarousal. For them, doing things once is enough, and if nothing is going on they find it difficult to remain satisfied. They seek out sensation to make up for nonarousal. In contrast, low sensation seekers experiencing the same low level of norepinephrine are more content and happy.

My scores for boredom susceptibility hover near the bottom. I almost never get bored. I remember waiting in line for the original iPhone, over a decade ago. (At that time you couldn’t order it in advance.) I waited in line over five hours with not much to do. I couldn’t fiddle with my phone—because I was waiting for one of the first smartphones.

It was a situation similar to what Zuckerman’s original sensory-deprivation participants endured, except I had a Cinnabon nearby. How did I cope with the lack of entertainment? Easily. Even telling this story to my friends with a higher boredom-susceptibility score seems to irritate them.

Not Such a Bad Thing

In general, the thrill/adventure-seeking and experience-seeking components reveal the style of thrill seeker a person is. The disinhibition and boredom-susceptibility components suggest how much trouble people will get into with their sensation seeking. All told, the behavioral-inhibition and behavioral-activation systems and higher levels of dopamine might suggest that a person is drawn toward more sensations, but they do not determine what type of sensations might be appealing.

What distinguishes high sensation seekers is that they respond to fear differently than most of us do, all the way down to the neurochemical level. They are able to remain calm in extreme circumstances. One of the things that I heard over and over from high sensation seekers is “Analysis is paralysis.” Instead of analyzing situations, they jump headlong into them and trust their bodies and minds to respond as needed. The goal is to not think about what to do too soon and, of course, not too late.

All in all, that’s not such a bad thing. Many of us do the opposite: We analyze each worry that pops into our mind.

During their high-sensation activities, sensation seekers handle the task in the moment. The rest of us tend to overanalyze situations that never arise and fail to act on the ones that do. We like to think we would act if a situation demanded it, but in reality, many of us stand passively by, hoping someone else will. This is a well-documented phenomenon, the bystander effect.

Can acting without fear—even without thought in some cases—be problematic? Of course it can. But I think we need people like this around when things really go south.

High sensation seekers see potential stressors as challenges to be overcome rather than threats that might crush them. Instead of dodging or running from a threat, they dive into it. This not only helps them resolve challenges but also boosts their belief in their ability to handle such challenges in the future. This mindset is a buffer against the stress of life. It increases their hardiness and resilience in the long term.

High sensation seekers report lower perceived stress, more positive emotions, and greater life satisfaction. Extreme activities bring them peace, confidence, and happiness.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.