Moderation Is the Key to Life

Health, well-being, and success rest on one principle: In all things moderation.

By Carlin Flora published July 4, 2017 - last reviewed on October 24, 2022

When a kid is tearing through a big bag of candy or enjoying a raucous game of indoor soccer near the étagére, the adult in the room will inevitably say, "This isn't going to end well." What an irritating comment to the child; by her own logic she is having a good time and there is no way this marvelous activity could take a turn for the worse! Right before her stomach starts to ache, or grandma's favorite snow globe crashes to the floor, the child can be said to have reached the peak of her experience. A researcher studying this phenomenon would graph it as an inverted "U": The effects of a specific experience are more and more positive until maximum arousal occurs and the effects suddenly become more and more negative.

If you're bored with your job and feeling dull and sluggish, motivation is hard to muster. At the other extreme, if you're overwhelmed by tasks or suffering an emotional crisis, your brain is flooded with stress hormones. Your ability to plan and learn is impaired, and over time your immune and nervous systems are compromised. But when you're actively engaged in a project—a little nervous, a little excited—you've reached a happy medium. Optimal levels of adrenaline and cortisol boost your concentration and performance; these hormones protect your body, in direct opposition to an excess of those substances hurting it. When you're optimally aroused, you're in flow, you're on top of the upside-down "U," and everything is juuust right.

In what's called "the Goldilocks effect," infants naturally tune in to experiences that are neither too simple nor too complex. Marketers know the golden mean as well: When presented with a product that is offered at low, medium, and high price points, the shopper typically chooses the middle option.

And yet, our culture valorizes extremes. "You can never be too rich or too thin" is a persistent message. People are no longer capable of watching just one favorite TV show; they binge on whole seasons at a time, forgoing sleep and other basic needs. If you're a real-estate junkie, you can gawk at garish celebrity compounds with 21 bathrooms or 100-square-foot "micro houses." Many have no problem downing a Hardee's Monster Thickburger (1,300 calories) or a Sonic Peanut Butter and Cookie Dough Dream Master Blast (1,870 calories). An opposing camp includes those who recoil in horror at a teaspoon of added sugar or a gram of gluten. Anything that happens to anyone is "Super Awesome!" Or, "The. Worst. Thing. Ever."

"We have a more is better algorithm built in," says Glenn Geher, a psychologist at SUNY New Paltz. "We evolved to like fatty food, but too much isn't good. Many substances or stimuli are beneficial in certain amounts, but then reach a tipping point after which they become harmful. We don't naturally moderate ourselves, because in ancestral conditions we didn't have to."

Many hover around the light-to-none end of the exercise spectrum, which is not surprising considering that early humans didn't have to gather the will to work out for an hour. "A more adaptive tendency for them was to move as little as possible to conserve energy," Geher says. "And that was fine because with a nomadic lifestyle they were already getting way more exercise than the typical modern-day American."

Further, a short-term focus primes us to eschew moderation, claims Art Markman, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas, Austin. We all discount long-term interests to some degree, and impulsive people have an even stronger tendency to do so. "Many activities that we overdo in the moment have a negative impact somewhere in the future," he says. "No particular cigarette is the one that kills a person; it's the accumulation of toxins over time that creates the negative health consequences. The motivational system doesn't take that long-term consequence strongly into account. It just decides: 'This feels really good right now, so let's do it.'" Even behaviors that are good only sometimes or pleasurable in the short-term, such as checking email, can scale up to an obsessive habit. The mere prospect of positive stimulation abets extreme digital behavior.

We've evolved to see things in black and white, rather than shades of gray. If you have to make life-or-death decisions about others in a split second, blunt categories are useful; even in low-stakes situations, putting people in buckets can be efficient. It's simpler to declare: My ex is a raging narcissist, rather than: Yes, my ex is quite high on the scale of some components of narcissism, but I also played a role in the dynamic that led him to leave. Nuanced assessments are mentally taxing, extreme labels are quick and easy to apply.

Balanced Behavior

The prevailing view of the positive psychology movement is that cultivating one's strengths and amping up positive feelings is always a worthy goal. But given that the inverted-U curve captures so much about human nature, Adam Grant, of the University of Pennsylvania, and Barry Schwartz, of Swarthmore College, were skeptical that that was invariably true. Indeed, in a 2011 literature review in Perspectives on Psychological Science, they found evidence supporting the notion that endlessly increasing "good" emotions and states is not always beneficial.

Take the concept of authenticity. Being a fake and a liar won't get you far, but people who claim to be "highly authentic" at work receive lower performance evaluations than others and are less likely to be promoted. Caring a lot about "doing you" prevents change and growth, and can lead to disclosing too much personal and sensitive information to others. Instead, Grant recommends striving to present a better version of yourself, rather than straining to make your inner self transparent.

It's an insight rooted in ancient wisdom: In Aristotle's enduring view, too little expression of certain traits, such as courage (cowardice), is undesirable while too much of the same trait constitutes a different character flaw (recklessness). Not pleasing others enough amounts to surliness, pleasing too much makes one obsequious—you have to be friendly, but not too friendly. The sweet spot in the middle is where you want to be.

Moderation is intrapersonally important, too. Sporting an always-sunny nature can hurt you. Extremely cheerful people earn lower salaries and even live shorter lives because they are often risk-takers. Likewise, moderate levels of positive emotions fuel creativity, but high levels don't. An excess of self-esteem is associated with work, health, and relationship woes. Even generosity and empathy have negative side effects when doled out in high doses. Too much generosity consumes so much of the giver's time and energy that it causes burnout; empathic overarousal can cloud judgment, cause bleeding hearts to back off to manage their own distress, or lead to sacrificial behavior that ultimately hurts more than it helps.

In The Upside of Your Dark Side, psychologists Robert Biswas-Diener and Todd Kashdan argue that you'll have a more meaningful and engaging life if you tap into the full range of emotions, including those seen as socially undesirable, such as anger. In a study published in the Journal of Anxiety Disorders, for example, Kashdan found that highly socially anxious people have more anger, and also suppress their anger more, than others do.

The point, explains Kashdan, a professor of psychology at George Mason University, isn't that we should never suppress anger. In a strong pitch for moderation, he notes, "There is ample evidence that habitual, reflexive emotion suppression is detrimental. Yet, uninhibited, impulsive, and tactless emotion expression may be equally damaging."

When we push aside uncomfortable feelings (a pain-killer reflex that is well-developed in our comfort-obsessed society), we deny ourselves the opportunity to learn from important indicators. Kashdan says the first step to moderating emotions is to analyze your own prejudices and figure out which emotional expressions are most effective in specific situations. "You have to recognize your own behavioral signatures. Which emotions are you allergic to? Remember that cultural and social contexts alter the benefits and costs of traits."

When you're angry, you don't have to lash out wherever you happen to be, Kashdan says. "But it's not about calming yourself, either. It's about being aware that your anger is a signal that someone or something is obstructing one of your goals. It could be a false signal, but if you think it's accurate, follow through and try to effectively remove the obstacle." Civil rights, for instance, aren't won without righteous indignation. "Anger is a tool that you want in your psychological Swiss army knife. If you don't understand and appreciate both the selfish and the altruistic motivations of others, you will not fare well," he adds. "Owning both sides allows you to flexibly deal with a variety of people and situations."

Attenuated Love

Love naturally takes extreme forms: Many neurochemical investigations have shown that during the early "infatuation" phase, your body pumps out high levels of norepinephrine, dopamine, and testosterone, leaving you euphoric and drawn to your new love as though he were a drug. It's a mechanism that evolved to make sure we bond and reproduce with others, a mission so important, it has no patience for half-measures. Over the course of about two years, infatuation tends to give way to an "attachment" phase, characterized by an increase in vasopressin and oxytocin and by feelings of security and contentment rather than unbridled passion.

Yet some people, particularly those whose love is unrequited, remain in limerence—a hyped-up but more anxious and tortured state—for years, unable to break the spell. Albert Wakin of Sacred Heart University, an expert on limerence, thinks of it as a combination of obsessive-compulsive disorder and addiction (to another person). He reports that 5 percent of people who suffer limerence have trouble shaking it, to the point where they can't function well in their day-to-day life and spend up to 95 percent of their time thinking of their beloved. Social media fuels this form of romantic intensity as it provides constant updates about and photos of the person who is already looming too large in their mind.

In one study, researchers found that those who experience rejection while still in the infatuation phase can experience profound feelings of loss and depression (the heartache most of us are familiar with) and can even be moved to engage in the most extreme of all behaviors: suicide or homicide. The areas of the brain activated in the romantically forlorn are the same as those involved in cocaine addiction, which, study authors conclude, may help explain how otherwise stable people can get obsessive when spurned.

Though it's short of outright rejection, ambivalence is powerful fuel for what researchers call "the unrequited love narrative." In Unrequited: Women and Romantic Obsession, journalist Lisa Phillips wrote about her own gripping belief that her doomed love story would have a happy ending. She fell in love with an unavailable man who hemmed and hawed over whether he should leave his girlfriend for her. She focused on him obsessively and couldn't stop herself from calling, messaging, and following him. "I was responsible for my extreme behavior," Phillips says. "And I was responsible for the fact that this person was treating me poorly and I was tolerating it. I now know that extreme feeling for someone else has nothing to do with whether or not you can have a fulfilling relationship over the long term. It's important to pay attention to the 'why,' when you love someone asymmetrically."

At the other end of the love-scale sit those who avoid it, despite needing it. The desire to belong and to be close to others is universal, but those with an "avoidant" (as opposed to a "secure" or "ambivalent") attachment style tend to push others away when they sense their independence is being threatened. Forged in childhood, attachment style is the way we tend to respond to the availability of partners or potential partners. Researchers estimate that about 20 percent of the population has an avoidant orientation. Psychiatrist Amir Levine and therapist Rachel S.F. Heller, the authors of Attached, recommend that avoiders pair up with people who have a secure attachment style, since an anxiously attached partner will continually annoy an avoidant. Conscious awareness of our own patterns can, over time, override or, at least, let us live happily with these ingrained modes of relating.

To counteract the unrealistic ideal of a committed relationship marked by constant desire and heroic sacrifices, Aaron Ben-Zeév, professor of philosophy at the University of Haifa, touts the notion of "mild love," characterized by calmness, caring, kindness, and loyalty. It's the steady diet of simple pleasures that is essential. Moderation is sometimes best achieved over the long term, when less passion may be offset by moments of intense passion (or at least rosy memories of an initial infatuation).

Moderate Appetites

A key to moderation is not becoming fixated on one part of life but, instead, taking a big-picture view so that assessing your overall balance of priorities is possible. A total preoccupation with food, for instance, is not only extreme but ineffective. "What you eat and drink is not everything when it comes to your health and longevity," says Susan McQuillan, a dietician and food writer. "Exercise is important, as are other lifestyle habits, stress levels, and family history. Some people put too much emphasis on food and think they're controlling everything with what they eat. We all know people who lived into their 90s and ate convenience foods every day."

"The classic rule for nutritionists is that there are no good foods, there are no bad foods, and you should eat everything in moderation," says McQuillan. "Some foods are not the best source of nutrients, but they still provide energy. When my daughter was young, we ate healthily most of the time, so I didn't have to worry about what she ate at a birthday party."

That sounds reasonable, but human hankerings go wild in an environment where engineered-to-binge snacks, such as Cheetos and Oreos, can be bought at every corner. Planning and cooking well-balanced meals is often a lot harder than turning to the extremes of a processed-food regimen or a restrictive "healthy" diet that limits the burden of choice. So-called "health foods" are often far from it: A fridge full of pressed juice in pretty bottles is appealing, yet all that "detoxifying" may actually flood your body with sugar.

It's true that a plan to eat in moderation might justify a varied diet that is actually worse than a less-varied diet focused on fruits, vegetables, and lean protein. A 2015 study out of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston found that diet diversity, or less similarity among the foods one eats, might be linked to lower diet quality and worse metabolic health. But if you know you are not going to fall into the "all healthy, all the time" category anyway, then aiming for diversity may at least keep junk-food cravings in check.

McQuillan's centrist strategy for living with a sweet tooth involves never buying cookies, though she does bake them from scratch. "Don't tell yourself you can't have sweets at all, because you're just going to rebel and overdo it," she says. One study of dieters confirms this advice: Those allowed a planned "cheat day" when they could indulge in treats were more motivated and able to follow through with their diet. They were also in a better mood throughout the process. Another study published in the Journal of Health Psychology in 2015 found that dieters consume more food after exercising than non-dieters do, calorically canceling out their effort.

Moderation and mindfulness go hand in hand: A 2016 study led by Jennifer Daubenmier at the University of California, San Francisco, shows that bringing awareness to the present moment and savoring food leads people to make better choices and recognize when they are hungry, satisfied, or full.

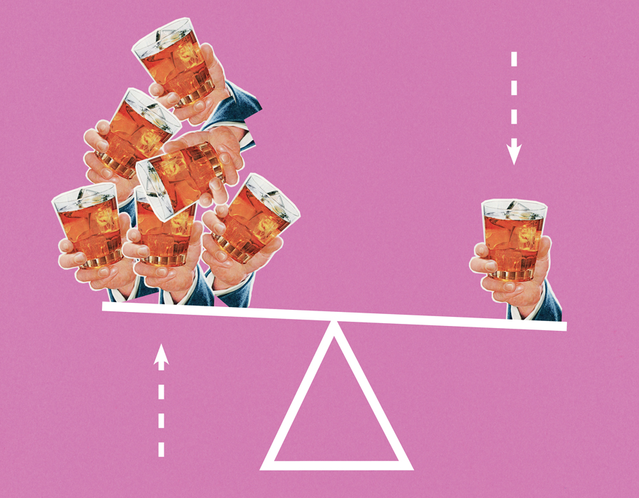

Alcohol's inherent disinhibiting effect makes it a particularly hard substance to consume moderately. However, total abstinence is too draconian for some and can trigger failure—a little relapse can lead to a hard fall off the wagon. A comprehensive review in the journal Clinical Psychology of the "harm reduction" method, in which therapists work with alcoholics to limit the amount they drink, found that these interventions are effective for some people because their imbibing is viewed in more than black-and-white, all-or-nothing terms.

Middle-of-the-Road Work Habits

Adherents of the American Dream believe that working to the max is the secret to success. But Grant and Schwartz, in their analysis of the prevalence of inverted-U-shaped effects, found strong evidence that moderation also gets results on the job. For example, "learning orientation" is the extent to which bosses encourage proactive learning and competence development among their employees. One study that Grant and Schwartz reviewed examined management teams in a Fortune 100 company and discovered that those with moderate (as opposed to high or low) learning orientations earned the most profits.

In an earlier study led by Ellen Langer, of Harvard, researchers asked people to translate sentences into a new made-up language. Subjects who practiced the language moderately beforehand made fewer errors than those who practiced extensively or not at all. High levels of knowledge can make people too attached to traditional ways of viewing problems across fields—the arts, sciences, and politics. High complexity in a job role exacerbates stress, burnout, and dissatisfaction. High conscientiousness is related to lower job performance, especially in simple jobs where it doesn't pay to be a perfectionist.

How long we stay on the clock and how we spend that time are under great scrutiny in many workplaces. The young banker who eats lunch at his desk is probably seen as a go-getter, while his rambunctious colleagues who laugh and gossip over a leisurely conference-room meal get dirty looks from the corner office. "People from cultures that value relationships more than ours are appalled by the thought of eating alone in front of a computer," Markman says. Social interaction has been shown to boost mood and get people thinking in new directions and in ways that could enhance any post-lunch effort.

Markman also promotes off-task time. "Part of being a good thinker is encountering things that are seemingly unrelated to what you are working on at the moment but give you insights into your work," he says. "Also, a work day that drags on too long crowds out other sources of life satisfaction, such as relationships. There is a lot of research showing that a positive mood leads to higher levels of productivity and creativity. So, when people do things to boost their life satisfaction, they also make themselves more effective at work."

Many prolific and prominent professionals build flexibility and leisure time into their schedules. Stephen King writes for a few hours in the morning, and then may or may not return to his desk in the afternoon. Even Charles Darwin reportedly dedicated just four hours per day to serious tasks. According to neuroscientist Josh Davis, the author of Two Awesome Hours, an even lighter schedule is sufficient, as long as conditions—such as not being tired or hungry—are right for peak productivity.

A creative person enraptured in a project, barely pausing for a drink of water, is a compelling image and might capture how some great works come about. But researchers make a distinction between "obsessive" and "harmonious" passions, with the latter coming out ahead. Scott Barry Kaufman, the scientific director of the Imagination Institute, based at the University of Pennsylvania, explains that people who are obsessively on-task are rigid and find it hard to disengage. Their habits put them at risk of burning out. Meanwhile, harmonious passion is correlated with the joyful state of being fully immersed in an activity.

Dare to Be Average

Setting up camp in the middle ground requires some thought and planning. Markman, the author of the book Smart Change, notes that you have to make certain things quite hard to do. "The motivational system is very good at clearing the decks for action. When you really want ice cream, you become more sensitive to information that relates to acquiring it. When I lost a lot of weight 15 years ago, I made the remarkable discovery that you can't eat ice cream that's not in your freezer."

Markman applies moderate thinking to many areas of life. He and his wife have a pact: They don't bring their phones into restaurants, so they won't be tempted to take a peek. And if his kids want to sit in the front passenger seat, they have to put their phones away so they can be engaging companions.

Replacing bad habits with good ones and establishing healthy systems for living moderately is easier when you have an underlying philosophical motivation to do so. If you value flexibility in setting goals and relating to loved ones, precision in thinking and speaking, and sympathy in judging other people, and you reject lazy, simplistic reasoning and mindless actions, then you're a true believer in the middle ground.

Moderation in All Things, Even Moderation

Every great rule has exceptions, and there's a time and place for extremism.

When the writer Samuel Johnson once walked into a party, someone said to him, "Will you take a little wine?" Johnson replied, "I can't take a little. Abstinence is as easy to me as temperance would be difficult." When Gretchen Rubin, the author of Better Than Before, read this anecdote, she immediately recognized herself (though her poison is sugar, not alcohol). It led to her concept of dividing people, for self-help purposes, into "abstainers" and "moderators."

"This distinction has to do with how people resist strong temptations because everybody can be moderate about weak temptations," Rubin says. "I'm a hard-core sugar abstainer, but I can take or leave potato chips." People assume Rubin is an abstainer because she has a lot of willpower. "The fact is, I don't have enough willpower to have a little bit of sugar. It's easier to have none." Banning frees her from having to make constant internal negotiations about which and how many candies, brownies, and cookies she can have.

"It's not about what worked for some billionaire, it's about what works for you."

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: Roman50/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Syda Productions/Shutterstock