Freeing Up

Inherited wealth felt more like a burden than a blessing to a young man, until he found the "courage of his insignificance."

By Jeremy E. Sherman Ph.D. published January 3, 2017 - last reviewed on April 7, 2021

At 16, I was given a small fortune, and with it confusion and shame that took me decades to shake.

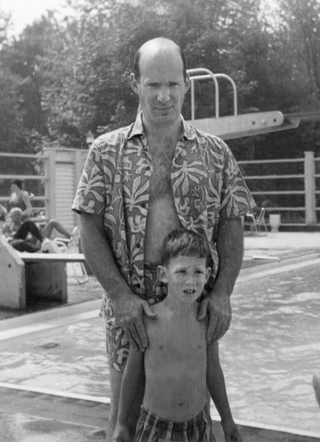

In the 1940s, my father, Gordon Sherman, dutifully went into his father's business, an auto parts company that they built into the international franchise Midas Muffler. Despite his success, my father was never a buttoned-up corporate type. With the soul of an artist and a wide-ranging intellect, he spent his free time memorizing Shakespeare and playing bagpipes, piano, and oboe. He raised orchids and turned whole rooms in our Chicago home into aviaries for hummingbirds and finches.

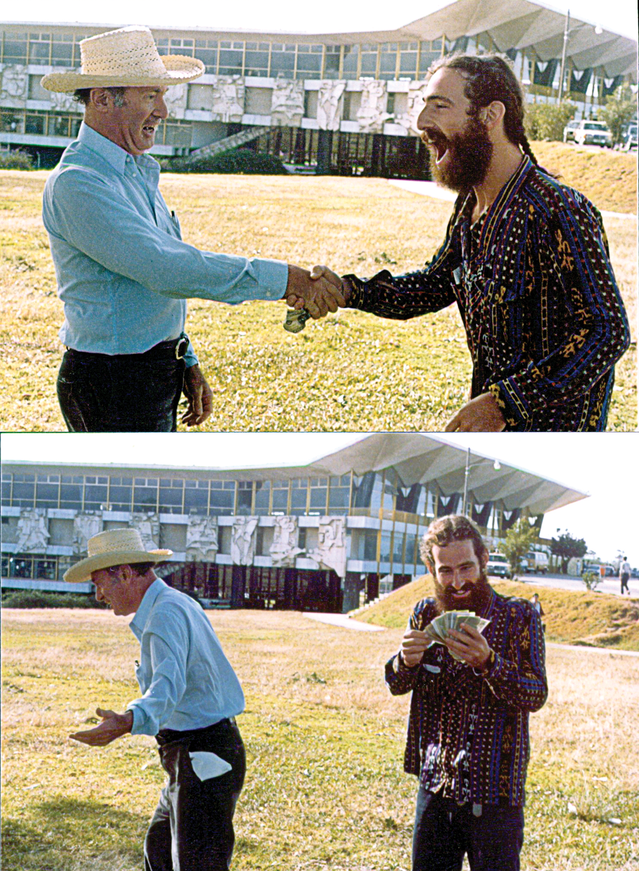

The Vietnam War drew him into work for progressive social change. He donated large sums to support the efforts of public advocate Ralph Nader and community organizer Saul Alinsky. During the trial of the Chicago Seven in 1969, he invited the young defendants to join him for lunch, seated directly across from their presiding judge, at the prestigious Standard Club—a provocation that led to his membership being revoked.

By his own admission, my father acted out a bit in part because he regretted not really having chosen his own career. He often told his four sons that we wouldn't be allowed to work at Midas unless we were "35 and failures." Though he explained that there were tax purposes for bequeathing money to us when we were so young, I suspect that my father also did it because he wanted us to have what he had lacked—radical freedom to choose our own paths.

To me, the inheritance didn't feel like freedom. I felt it more like an intense pressure to do something to justify what I was given. It was as if the fates had said, "Here's a lifetime's salary. Now make yourself worthy of it."

An early impulse was to give my inheritance to something more deserving of it than I. Dropping out of college, I moved into the country's largest commune, The Farm, in rural Tennessee. Members signed a vow of poverty and relinquished their personal possessions. I did just that and jumped enthusiastically into a nonstop work party with the commune's 1,400 other members. We built our homes from scavenged materials, farmed the food for our strictly vegan diet, and used car batteries to generate electricity. We aimed to model an exemplary sustainable lifestyle and assumed that as the world stumbled toward post-industrial chaos, many others would join us. I adored my voluntary peasantry and how it freed me of guilt. I married within the commune and had my first child there.

About six years in, however, I realized that people weren't fleeing the mainstream in droves to follow us into the woods. I maintained my commitment to the commune by focusing on my virtuous decision to live there, though my doubts about its impact grew. Once on a trip home to visit my parents, they encouraged me to go hear a lecture about the nuclear arms race. Scanning the crowd, I realized that plenty of people were clearly pursuing social change without dropping out of society. A few months earlier my grandfather had died—and had left me a million dollars contingent on leaving The Farm. It was the impetus I needed to make a change. I decided to wipe the dirt off my hands and risk sullying my clear conscience by living and working within the system.

Pivoting to activism, I cofounded a national grassroots lobbying campaign for nuclear disarmament, designed advocacy campaigns for green businesses, donated to environmental causes, and got a master's degree in public policy. But eventually, I became disoriented and disillusioned on that path as well. In the Reagan era, my work and philanthropy seemed to yield negligible results. The world's woes were mounting and it was hard to find the pulse of any movement making a real difference. I began to feel powerless. Shame about my wealth returned.

Around the time that my work life stopped working for me, in the late '80s, both of my parents died. My marriage was falling apart, and I descended into a profound midlife crisis, frustrated with how little I had accomplished in my first 40 years. And I had nobody to blame but myself.

Many people feel that they haven't accomplished enough, but they can usually point to external circumstances that held them back. Inheritors have no such excuse for their shortcomings. Having been granted limitless opportunity, I felt that my failings were mine and mine alone. I couldn't pretend that circumstances had prevented me from doing anything.

My father used to talk about the "courage of his insignificance." During my crisis, those words echoed in my mind along with those of another personal hero, the futurist Buckminster Fuller, who asked, "What was it you were about to do before you were told you have to earn a living?" For me the question was "What was it you were about to do before you thought you had to justify your inheritance?"

When trying to change the world, I was outwardly focused. During my crisis, I crumbled inward and admitted for the first time how much of my outward activism had been driven by the need to prove myself and erase my shame. I also began to notice that my struggle to prove myself was a variation on everyone's challenge. We're not born with a packing slip listing the contents of our character or with instructions for making the most of who we are within an ever-changing world. We're all guessing how to do the most with what we're dealt. I stopped feeling so exceptional and so bereft.

Released from the feeling that I had something to prove, I relaxed into what would become my life's work. I started writing a book about the nature of the tough judgment calls we all face. I went back to school for a Ph.D. in evolutionary theory and decision theory, which led me to a 20-year collaboration with the life and social scientist Terrence Deacon. When I met him, Deacon had just turned his attention from the origin of language to the origin of life, or more specifically, the evolution of purpose-driven organisms from aimless chemistry—how "mattering" emerges from matter. Making use of my aptitudes and appetites, my writing and teaching today spans from life's beginning to the practical challenges that keep us up at night.

Am I changing the world?

I hardly ever wonder anymore.

I'm glad for the work I did on crucial causes, though these days, I'm absorbed with the ideas that engage me most. Feeling purposeful makes moot the question "Am I being productive enough?"

I live mostly off what remains of my inheritance and rarely feel guilty about it. The feelings do resurface occasionally. I've felt pangs upon discovering that an ex's new boyfriend is a self-made man, or when talking with friends who struggle to earn their daily bread. My daily bread is always there for me. I've never once had to wonder how to pay my bills. Although I'm not a self-made man, I like what I've made of my fortunate circumstances. I like it well enough that, nose to the grindstone, I continue doing my work, taking notes on what it's like to be a human finding one's way to fruitful engagement.

Read Jeremy Sherman, Ph.D's, PT blog: Ambigamy

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.