Fear

How to Overcome Fear and Win the Day

Three powerful strategies to improve your performance in sports and life.

Posted August 3, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Conventional attitudes about competition produce stress and undermine performance.

- People can benefit from seeing competition as bringing out the best in each other.

- Self-compassion and detaching from the outcome can improve performance.

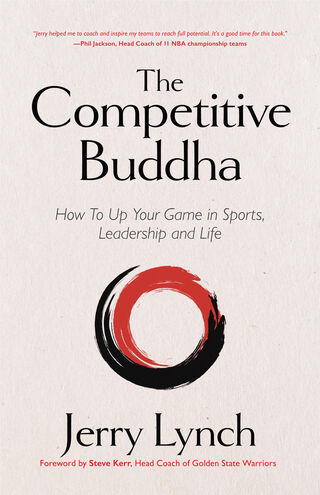

From Olympic competition to America’s highly competitive society, too many of us push ourselves to win—in our sports, careers, relationships, and life. To deal with the resulting stress, some of us turn to mindless distractions while others seek relief in exercise or meditation. But there is another way. As sports psychologist Dr. Jerry Lynch explains, we can improve our performance, well-being, and peace of mind with a new concept of competition.

Lynch describes this new concept in his book, The Competitive Buddha (2021). With its message of mindfulness and detachment, Buddhism may seem miles away from competition. And yet, as Lynch explains, the Buddha himself excelled as an athlete, competing in horsemanship, wrestling, and archery. He “followed the original Latin origin of the word, competere, which means to seek together” (personal communication, 2021). This kind of competition means working together to bring out the best in each other.

According to Lynch, “This is what we call true competition. When we compete in the conventional sense, he says, “we’re afraid we’re going to lose.” But when we “start thinking and competing in a Buddha way, it takes away a lot of fear.” True competition, Lynch says, is a whole new mindset: "It’s not about winning and losing. It’s about cooperating with each other.”

Courage and Compassion

Competing in the Buddha way brings us greater compassion for one another. We see others not as opponents but partners on the path. It also brings us greater compassion for ourselves. For Lynch, self-compassion (Neff, 2009) leads to greater courage. When we lack self-compassion, he explains, “we're hard on ourselves because we lost, or we made a mistake, or we didn't do something right.” In fact, he says, “I think the biggest fear is not the fear of losing. It’s the fear of what happens after we've lost and what we do to ourselves. So if I lose this game, or lose this match, I beat up on myself. But if I have self-compassion, I understand that loss is part of life and that I'm learning from that loss. And I'm a better athlete, a better person, and a better version of myself because of it.”

Embracing the Wisdom of Nature

Buddhism, says Jerry Lynch, is “not a dogma,” but the wisdom of following “the laws of nature. It’s how things work.” If you rub your hand against the grain of a piece of wood, he says, “you’re going to get splinters” and that hurts. “Don’t rub that way, rub with the grain. Don’t swim upstream. Swim downstream.” The natural principles in Eastern philosophy, Buddhism and Taoism, reflect the way nature works—the cycles of the seasons, the energies of day and night, yin and yang. Nature can teach us important lessons like the power of perseverance. Water is gentle and nurturing, yet with progressive effort can cut through solid rock, as the Colorado River created the magnificent Grand Canyon. Becoming more aware of nature’s principles brings us the wisdom to flourish in our personal and professional lives.

Letting Go of the Outcome

A familiar Buddhist teaching is that attachment causes suffering and detachment brings peace of mind. But what does this detachment mean? In sports and life, Jerry Lynch says,” It's not detaching from caring, it’s not detaching from your efforts, but detaching from the outcome. Because if you're attached to the outcome, you're going to feel tight, tense, tentative, stressed, anxious. So what we want to do is detach from the outcome; let go of the need to win, because you cannot control it.” This kind of detachment, he says, “creates freedom, liberation. And when you feel free and you're liberated, you're more relaxed and calm. And guess what happens to your performance? Whether you're writing a book or performing in an arena, or something else, you feel so much more relaxed. You're so creative, and your performance goes up.”

Presence and Process: Winning the Day

This kind of detachment focuses on process, not outcomes, a strategy of “winning the day” Lynch developed working with an elite tennis team at Middlebury College. The team had made it to the national championship finals the year before, then lost the final match. When he met with the team in January, they were all fired up and determined to win that year’s championship. “I could feel the tension in the room,” he says. He told them, “if you keep this energy going until June, you'll never make it there, you'll burn out. It's just too much. Instead of thinking about winning the championship, which you cannot control—no one can control outcomes and results—what you can do is control the little things in life.” So he asked them to “take one day at a time,” to think of “the eight things you can do today, individually and as a team” that would win the day, giving your best effort with things like meditation, stretching, hitting a bucket of balls. “You will play your best tennis if you focus on winning the day. And stop getting so tense and tight and tentative and stressed and anxious about having to win the national championship. Everyone's going to feel tight and tense, even your opponent. So instead of feeling that, how about feeling calm and relaxed, because you can focus on what you can control?” This approach—setting a realistic goal and specific steps to reach it—brought them greater hope (Snyder, 1994).

The tennis team took this message to heart, put “win the day” on their t-shirts, and began practicing those eight little things. That year they went to the championship finals wearing those shirts, focused on winning the day, and won the national championship.

For each of us, “winning the day” means putting our values into action, believing we can make a difference in our lives, one step at a time, with what Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck (2007) calls a growth mindset. Jerry Lynch says he lives this way himself, following 10 things he can do to “win the day” in his daily life. This includes meditation, reading, exercise, eating a healthy diet, and “doing all the things that are important, that make me a whole person, make me a better version of myself, athletically, as a friend, as a father, as a spouse as, as a psychologist. I'm just trying to be the best version of myself.”

In The Competitive Buddha and his work with teams, Jerry Lynch shares these lessons that can help us flourish in our performance in life. “The message from the Buddha,” he says, “is one of cooperation, collaboration, connection, compassion, coming together, in a slow incremental way in a safe environment. And we can determine that through winning the day, which we can control, which then allows us to master the moment.”

What little things would help you ”win the day” in your own life?

This post is for informational purposes and should not substitute for psychotherapy with a qualified professional.

References

Dweck, C.S. (2007). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

Lynch, J. (2021, July 16). Personal communication. All quotes from Jerry Lynch are from this source.

Lynch, J. (2021). The competitive Buddha: Sacred wisdom to awaken mastery and mindful leadership in sports and life. Miami, FL: Mango Publishing.

Neff, K. D. (2009). The role of self-compassion in development: A healthier way to relate to oneself. Human Development, 52, 211-214.

Snyder, C.R. (1994). The psychology of hope. New York, NY: Free Press.