Depression

The Tragedy Paradox: Why We Like Sad Music

Ever wonder why sad songs can make you feel happy?

Posted November 30, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Despite avoiding negative emotions in everyday life, we are often drawn to them in art.

- Research supports that sad songs can make people feel happy.

- Empathy, or the ability to get lost in the art, predicts who will feel happy listening to sad music.

Emotion, in particular sadness, has played an important role in art and music throughout human history and across human cultures. Music, in particular, often features themes of love and loss, showing how central loss and the sadness it creates are to our shared experience.

Interestingly, many people report that they enjoy listening to sad music because it makes them feel happy. This is an example of the tragedy paradox: the observation that even though we try very hard to avoid misery and to feel sad when we see it in art, it is very often somehow pleasing (Morreall, 1968). Why is this so?

First, what is it that makes sad music sad? The lyrics to a sad song, if there are lyrics, often feature the normal triggers for feelings of sadness; the typical trigger is the loss of a person, a relationship, money, status, or even the loss of a valued object. Sad songs also share a similar musical structure. Music that evokes sadness is generally low in pitch, uses a restricted range of pitches, is often written in a minor key, and has a slow tempo (Sachs et al., 2015).

When we listen to sad songs, they tend to evoke physical reactions typical of the emotion of sadness–a decrease in energy, a change in measures of autonomic nervous system activity like blood pressure, heart rate, heart rate variability, and skin conductance, and often tears, taken as an indication of physical activation.

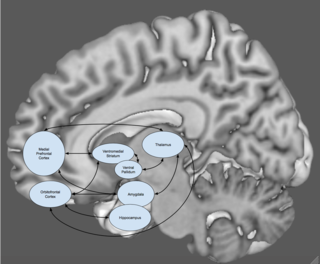

In the brain, fMRI studies show that sadness triggers an increase in the activity of parts of the limbic network, including the anterior cingulate and insular cortex, as well as in the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, and caudate. Sad music tends to activate these same brain regions, lending support to participants' reports that the music is truly sad.

Why Sad Songs Can Make You Happy

There have been a number of different explanations offered for the tragedy paradox. Aristotle suggested that watching a tragic play allowed the audience to experience negative emotions and, in doing so, to purge that negativity from their systems in catharsis.

Modern theories run the gamut from the possibility that sadness in art is different from sadness in everyday life, so sad art is actually producing a positive emotional state, mislabeled as sadness, or that sadness in art makes us feel more connected to others, or the suggestion that sad art produces both sadness and pleasure mixed together.

Sadness tends to last longer than pleasure, so sadness is what remains at the end of the music, and that is what is reported. There is even a hormonal explanation offered: The hormone prolactin, usually released in response to tears, grief, and sadness, acts to encourage us to form attachments with other people and bond.

Prolactin is also secreted when we listen to sad music. This may make us feel comforted and consoled, especially when we realize that we’re not actually experiencing real mental pain. It’s just the music and the benefits of prolactin (Sachs et al., 2015).

Using a relatively new tool in the fMRI toolbox that makes it possible to look at neural activity evoked by naturalistic stimuli like an entire song, Sachs et al. (2020) examined how sad music affected the pattern of activity within the limbic network and how that pattern of neural activity, along with individual differences in personality traits, were related to the intensity and the enjoyment of sad music.

Because empathy had previously been shown to predict who would report that sad music made them feel good, participants were separated into two groups on the basis of their scores on a paper and pencil test measuring empathy. Empathy measures assess the ability to get absorbed and lost in a story or a piece of music to feel what the characters in the story might be feeling. Group one scored high on the test, while group-two participants scored lower on this scale.

Participants were then asked to listen to an instrumental piece of music that reliably evoked sadness. The musical pieces used were instrumental only and had been found to reliably evoke feelings of sadness and happiness in pilot study volunteers. (I had fun imagining which musical pieces I would use to evoke these emotions and came up with quite different ones than the ones used in this study.)

Participants listened to the music while undergoing fMRI scanning. When the scans were completed, participants were asked to listen to the musical pieces again (outside of the scanner) and rate both the intensity of emotions they felt during the music and their enjoyment of the music.

Results

Activation of the parts of the limbic network that are usually stimulated by negative emotions like sadness was seen when the participants listened to sad music. (The results of the scans when participants were listening to happy music were not reported in this paper.) Specifically, the ACC, amygdala, and ventral striatum showed high levels of activity when listening to sad music. As sadness levels increased, so did the activity in these areas.

Empathy scores predicted sadness ratings, with the most empathetic participants tending to rate the music as the saddest. And empathy also predicted differences in the activation of the brain regions involved in the response to the music as well as in brain regions involved in processing information about understanding and resonating with the emotions of others like the medial prefrontal cortex. Activity in auditory, visual, and frontal brain regions was more synchronized in highly empathetic participants than in those scoring low on empathy.

Results like these help researchers understand how two very different aspects of an emotional experience—one positive and sought after and one negative and often avoided—map onto patterns in neural network activity.

References

Morreall, John (1968) "Aristotle and The Paradox Of Tragedy," The Angle, 1968(1). Article 2. Available at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/angle/vol1968/iss1/2

Sachs, M.E., Damasio, A., and Habibi, A. (2015). The pleasures of sad music. A systematic review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 1-12.

Sachs, M.E., Habibi, A., Damasion, A., and Kaplan, J.T. (2020). Dynamic intersubject neural synchronization reflects affective responses to sad music. Neuroimage, 218, 116512