Career

The Problem With "Check Your Privilege"

Why does "check your privilege" backfire?

Posted August 21, 2019 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

You have probably heard of the “privilege walk.” It is a task that is used in many classrooms to illustrate what it means to say that some people are more privileged than others. A group of participants stand next to one another in a line. The group is asked a series of questions designed to identify circumstances of privilege or lack of privilege that individuals in the group have experienced. Participants take one step forward each time an instance of privilege is named, and one step backward for each obstacle.

The task "forces participants to confront the ways in which society privileges some individuals over others. It is designed to get participants to reflect on the different areas in their lives where they have privilege as well as the areas where they don't."

For example, the first four questions of an online version of this task are as follows:

- If your ancestors were forced to come to the U.S. not by choice, take one step back.

- If your primary ethnic identity is "American," take one step forward.

- If you were ever called names because of your race, class, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation, take one step back.

- If there were people who worked for your family as servants, gardeners, nannies, etc. take one step forward.

Of course, we will find that white, American males of means will find themselves in the front of the row, and members of all other groups will find themselves positioned at various distances behind the white males. For the full set of questions, click here.

Calling Out Privilege

How do people respond to this task? Let’s consider the responses of people at the front of the pack—the people of privilege. They tend to respond in two ways. Some experience an enhanced awareness and appreciation of how they have been advantaged in comparison to others. Others, however, are offended. They often experience a sense of being told that they did not earn their success. They often feel personally blamed for the plight of those who are less privileged.

There are good reasons why some privileged folks might feel offended by the task. The “Check Your Privilege” task is not a neutral one. While some advocates of the task say that it is designed merely to “prompt reflection”, the unspoken purpose of the task is to prompt a certain type of reflection—a sense on the part of the privileged person to acknowledge his or her part in maintaining a racist, classist or sexist society. In other words, it is experienced as a form of being “called out."

Is it true that privileged folks did not earn their success? Is it true that they are responsible for the plight of the less privileged? The answer is not so simple.

What Is Earned and Unearned?

I am a white male living in the United States. Our social system is biased in favor of people like me. I have had both success and failure in my life. Whatever successes I’ve had, to be sure, I did not achieve alone. I had help. In fact, I’ve had a lot of help—both direct and indirect. I’ve been helped in ways that are nicely captured by the “Check Your Privilege” task. It is unfair that I have had systemic advantages while others have not. And so, people who are privileged have a moral duty to work toward correcting systems of disadvantage.

But wait. Although the advantages I have had are undeserved—I did nothing to earn them—the fact that I have had advantages does not take away from the fact that I nonetheless had to actively do something to achieve whatever successes that I have attained. While I did not earn my advantage, within that system of advantage, I still had to put forth hard work and effort to achieve whatever I have achieved.

While my hard work does not erase the advantage that that was bestowed upon me, my advantage doesn’t take away from the hard work I put forth in order to succeed. And neither trumps the other. Let me explain.

Earned and Unearned Success

Let's perform a simple thought experiment. Imagine two infants, one a white male and the other a female of color. Imagine that the white male has many advantages—wealth, a highly educated family, good schools, connections, and all the rest. Imagine that the girl of color not only lacks those advantages, but has a series of obstacles placed in her way—racism, sexual harassment, low expectations from others, discrimination, and so forth.

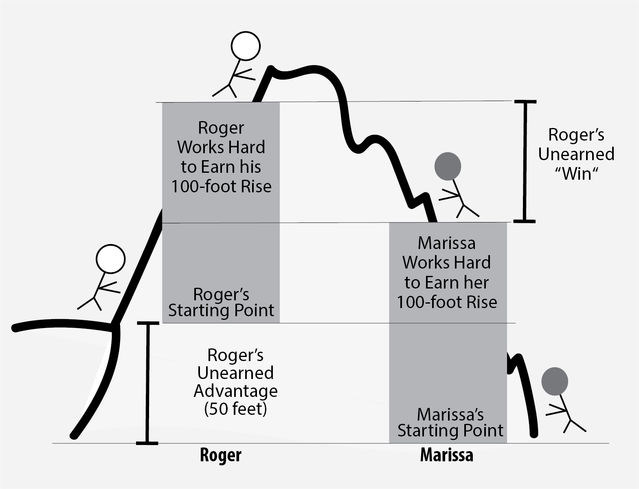

Such a situation would be like the two persons climbing a mountain. This is shown in the figure that accompanies this article. The climber on the left, Roger, starts off with an advantage—a head start. The climber on the right—Marissa—starts from the bottom. Let's assume, for the sake of this thought experiment, that both climbers worked equally has hard to get to the top of the mountain. All other things being equal*, as they climb, Roger and Marissa will make the same amount of progress up the hill—they will both climb, say, 100 feet.

Now, instead of comparing Roger and Marissa, let's look at each of their climbs individually. When we do this, we see that Marissa was able to climb 100 feet because of her effort and hard work. Through her hard work, she earned her 100-foot climb up the mountain. No one can take that away from her.

The same, of course, is true of Roger. Roger also climbed 100 feet as a result of his effort and hard work. Through his hard work, Roger earned his 100-foot climb up the mountain. No one can take that away from him.

Now here is the point: Both Roger and Marissa earned their individual rises of 100 feet up the mountain. However, while Both Roger and Marissa each earned their individual climbs, Roger did nothing to deserve his win—climbing higher than Marissa.

Roger earned his climb. He didn’t earn his win. Both of these statements are true at the same time. And again, one doesn’t trump the other.

When “Check Your Privilege” Backfires

In "calling out" the unfair advantage of the privileged over the less privileged, the two senses of what it means to earn one’s success are often confused. The person being called out is not simply being told that he had advantages, he is also being told that because of those advantages, he didn’t earn what he has achieved.

Much depends on what we mean by "achievement" here. If we mean comparative achievement—his "win"—it is true: Roger didn’t earn his win over Marissa. He did nothing to deserve the advantage he had over Marissa. However, if we mean his personal achievement—his individual and effortful 100 foot climb up the mountain, the situation changes. He did earn that. Just as Marissa did.

To the extent that a person of privilege works hard to climb his personal ladder, to say he didn’t earn his personal rise through hard work is an error. Not only is this an error, but it backfires as a political strategy. It gives the very person one wants to reach—the person of privilege—a legitimate reason to become defensive. When this happens, it is easy to dismiss the demand that one “check one's privilege.” In so doing, one loses the potential to recruit an ally in the fight for social equality.

Is There a Better Way?

Is there a better way to call attention to privilege and make the privileged folks on top want to work for social change? I think so. It involves using positive rather than negative moral persuasion.

“Check Your Privilege” backfires because it relies on public shame and guilt. The task suggests that the personal effort they put forth toward their personal achievements were in some way invalid. It makes the privileged folks on top feel as though they personally did something wrong to bring others down. And in a public forum, people feel pressured to accept this message out of fear of being called racist, sexist, classist or what have you. This form of public shaming is negative morality. It says, “You have done something wrong; now fix it.”

Positive morality works differently. It involves appealing to other's sense of moral identity—their sense of moral responsibility. This involves an appeal to the moral responsibility that comes with privilege. For any undeserved privilege, there is corresponding responsibility to others who have not had that privilege. Positive morality means making appeals to a person’s moral sense of self: the moral, compassionate, correct thing for a person of privilege to do is to attend to those who are less privileged. It says, "Person of privilege, your privilege comes with a moral duty. If you do this duty, you will be enhanced, not diminished.”

Don’t tell someone that they are responsible for the accident of living in a system that advantages them. Tell that person that there is moral dignity looking forward and taking responsibility for doing something about it.

----

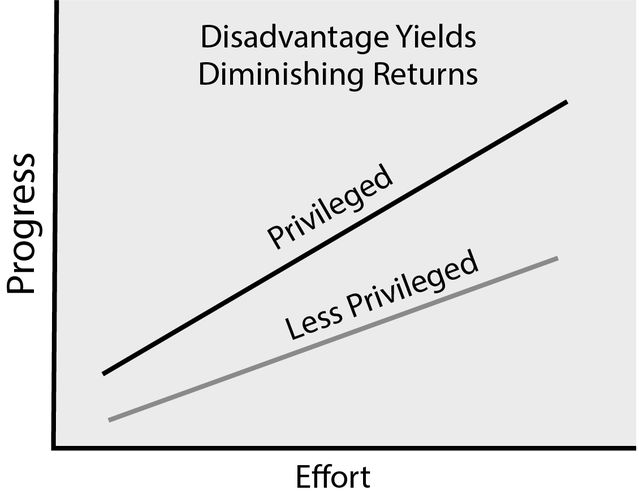

*Of course, Roger didn’t just get “a head start” up the mountain—he had a much smoother climb. In contrast, Marissa not only didn’t get a “head start,” but she also had a suite of obstacles placed on her path. And so, the climb is harder for Marissa than for Roger. The simple fact is that when this happens, advantage begets more advantage, and disadvantage brings about further disadvantage. The more success one has, the more success one achieves. The more failure one experiences, left uncorrected, one falls further and further behind. This situation is shown in the accompanying graph.

This post was inspired by Deborah Greel.