Trauma

Not Every Emotional Reaction Is a Trauma Response

5 myths and truths on the fight-flight-freeze response.

Posted June 11, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Trauma responses vary widely based on personal history, experiences, and cultural context.

- The long-term impact of trauma depends more on its integration into one’s life than the immediate reaction.

- Immediate responses to threat differ from the adaptations people may assume long after the event.

This post is the second of a series about dispelling trauma myths. (You can read the first one here.)

As a phenomenon, trauma involves a collection of experiences and reactions rooted in our fundamental need to survive in the face of overwhelming adversity. This includes responses mainly from the neuro-biological system, but also from psychological and social domains that work together to help us be protected, process the impact of those events, and adapt to life and its challenges.

Focusing on the traumatic event when thinking about trauma may make us forget that the response to the event is more important in the development of symptoms and possible dysfunction than the event itself. Trauma is bigger than the sum of its elements (meaning both the traumatic event and its lasting consequences) and becomes a significant problem when our reaction to a threat goes into crisis mode and fails to return to baseline afterward.

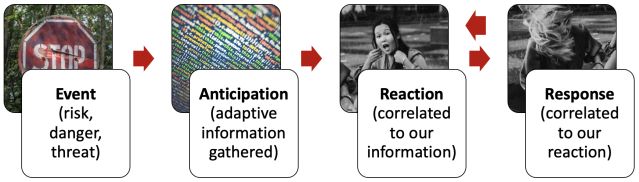

The way we react to an event depends on our perception of what’s threatening or dangerous, and the emotions linked to that perception. This perception is connected to the ideas we have gathered through our lives about what’s dangerous and what’s resolvable or unsolvable. Hence, we react influenced by experiences, cultural or societal values, and schemas.

For example, depending on how much we fear spiders, our brain could start preparing for the possibility of a spider attack as soon as we see spiderwebs (for those with a moderate level of fear) or as soon as it gets dark (for those with a high level of fear). For someone who is extremely afraid of spiders, we could expect them to panic if they feel a sensation on their skin that they interpret as a spider, because the response of their nervous system follows that interpretation or threat.

Trauma response: Submitting to the reaction

The innate response of our nervous system when encountering an event that we subjectively consider dangerous is linked to the survival circuits that get activated when the brain anticipates an extreme or severe threat that either makes us stronger to overcome the threat first or floppier if we were not able to recover safety.

It's important to understand that our reactions or the activation of the innate survival response do not constitute trauma on their own.

Everyone has the capacity to recover confidence and stability soon after shock or reactivity, which would bring the system to its pre-event functionality without any considerable repercussions. The term “trauma” applies when the system destabilizes, leaving lasting consequences.

Let’s go over some of the misconceptions about trauma responses and reactions:

Myth: Not all trauma involves a direct threat to survival.

Trauma is such a complex phenomenon that keeps the scientific community actively researching its nuances. Some experts argue that experiences like emotional neglect or shaming do not involving immediate physical danger but are traumatic. The literature points out that such experiences can make individuals, especially children, feel unsafe and question their self-worth, triggering a sense of threat and activating the body's survival circuits. So, even when they don't seem to be life-threatening, they activate survival protections that end up hurting their system.

What’s important to remember is that it’s not our cognition that assesses if the situation is life-threatening; rather, it’s our brain that assumes it, informed by our emotional responses, level of fear or stress, and perceived risk.

Myth: The trauma response is the same for everyone.

For many years, the fight-or-flight response was considered the definitive indicator of trauma. However, as our understanding of trauma has evolved, it has become clear that this is far from being the whole story.

First, fight-or-flight are just two of several trauma responses. They may be the most evident, but they are not even the first ones. The nervous system activates the response with the highest possibility of success in keeping the person “safe” from the anticipated threat.

Each person's reactions are highly individualized because they depend on one’s unique perception of threat and danger. That’s why our brains activate a response even before we have a chance to objectively assess the actual level of risk. While the initial response is automatic, the brain can quickly shift to a more objective assessment after the initial threat subsides.

Myth: The damage of trauma depends on the reaction during the traumatic event.

Our survival responses are part of our natural instincts, and our system is designed to bounce back and repair alterations once the task of protecting our life is over. The initial reaction activates the survival circuits but if we resolve the fear, our system does not get damaged.

The true impact of trauma is often seen in the aftermath. Primarily, it’s the time we take to recover a sense of safety that determines the extent of damage the system incurs. This involves the initial physiological and psychological responses, but most importantly, the ongoing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral adaptations.

Long-term damage from trauma is often related to how the event is integrated into one's life and psyche. For example, someone with strong social support and effective coping strategies may recover more quickly and completely than someone who is isolated or lacks such resources.

Myth: Those with PTSD live in a permanent state of fight-or-flight.

This myth may come from the image of the veteran living as if they were still at the front, but trauma can happen to anyone. Traumatized individuals adapt in different ways after shifting their operation into survival mode, and each person develops different survival strategies afterward. How each one adapts is obviously connected to the traumatic experience, but just a small percentage of those that suffer from PTSD were at war, and hence, we can’t really use that image to conceptualize how people with PTSD act.

Survival strategies are highly individualized, reflecting the specific circumstances each person needs to adapt to and their personal characteristics. That’s why some traumatized individuals with a dysregulated system may appear outwardly composed with no signs of fight-or-flight. Many individuals who internalize their symptoms may become physically ill before they recognize their internal emotional struggle.

Myth: Dissociation is always a direct response to threat.

Trauma is so complex that it’s difficult to use “always” or “never.” Dissociation, for example, may be an important component of the aftermath of traumatization or even an immediate response to a traumatic event, but not always.

Dissociation can manifest independently of trauma. In the name of adaptation, our brain makes changes to better respond to specific circumstances using the resources the person has or lacks, and dissociation is one of the ways our brain may protect us from overwhelming stress or shock by creating a psychological distance from the present moment.

For instance, a person in a traumatizing domestic violence situation might adapt by becoming submissive, numbing their needs to survive (disengaging). In contrast, a person in a violent environment might adapt by becoming aggressive or assuming a leadership role (compartmentalizing). In general, a person dissociates as an automatic response when they feel hopeless about their situation, but it’s normally a last resource when confronting a threat.

The way we respond to traumatic experiences varies greatly. Fear can become a habit that activates our trauma responses even without real danger.

For example, we might feel a fear of dying just by looking at an airplane, even if we have no plan to fly soon. If we recognize, however, that we are having an emotional reaction to the plane, and instead of letting it run as the anticipation of risk, we reflect on how safe we are in that moment, on the ground, the brain will not activate any damaging mechanisms. Thus, trauma could be stopped even before we face a traumatic event.