Emotion Regulation

How to Get the Most Out of Stoicism

Discover the power of being unperturbed by emotions.

Posted August 23, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Stoicism is often interpreted as not experiencing unwanted, difficult, or "irrational" emotions.

- Emotions are not completely under your deliberate control due to many factors.

- Deeper applications of Stoicism are possible through changing your relationship with emotions.

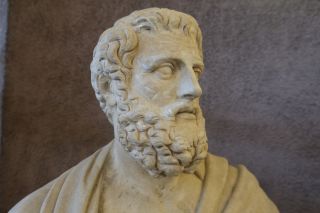

The practice of Stoicism has been helpful to countless people for the past 2,000 years. One of the simple but powerful ideas of the Stoics is that your ultimate well-being does not depend on forces outside your control.

According to Epictetus, for example, we can “make our desire and aversion safe against any setback or adversity” (Discourses, Book 1). In other words, we neither cling to the things we want that can be taken away from us, nor resist undesired outcomes if we can’t prevent them. This stance makes equanimity possible regardless of circumstances.

Emotionless Stoics?

Furthermore, the Stoics give examples of being emotionally unmoved even by extreme circumstances. Epictetus describes the example of Agrippinus, who had been condemned to exile and told that his estate would be confiscated. His response essentially was, “OK, what’s for lunch?” (Disc., Book 1).

For his part, Seneca writes about Stilbo, who lost not only his home but his wife and children. When asked if he had lost anything, he stated with apparent indifference, “I have all my valuables with me” (Letter IX).

These teachings have given rise to a common understanding of Stoicism that equates it with a lack of emotion. According to this perspective, a “true” or “good” Stoic is free of unwanted or unpleasant emotions. This idea is bolstered by the dictionary definition of “stoic” as “not affected by or showing passion or feeling” (Merriam-Webster.com).

Nevertheless, you probably experience unwanted emotions at times, even if you’re well-versed in Stoicism:

- You get worked up when a driver tailgates you.

- You feel resentful when you think you’ve been mistreated.

- You get prickly and defensive with your partner.

- You ruminate about something irritating a friend said.

- You’re fearful in some situations that aren’t actually dangerous.

Applications of Stoicism can help to diminish these experiences, but they can’t get rid of them altogether. The nature of emotions virtually guarantees that they won't be tamed completely.

The Origins of Emotions

Stoic writers tend to emphasize the conscious thought patterns that contribute to emotions. For example, Epictetus famously said in Enchiridion, “It is not events that disturb people, it is their judgments concerning them” (chapter 5). Similarly, Marcus Aurelius writes in his Meditations that the mind “makes what it chooses of its own experience” (Book 6.8).

These observations can make it sound as if you feel disturbing emotions only because you’re thinking about things the wrong way.

However, many factors besides explicit thoughts drive your feelings, and only some of them are under your deliberate control. They include:

- What you eat and drink

- Your energy level and blood sugar

- Learned associations from childhood

- Your history of trauma

- Unconscious core beliefs

- Your nervous system’s fight/flight/freeze reactions

Some Stoic writings explicitly make allowance for these experiences. For example, Epictetus describes certain “impressions” that “are not voluntary or subject to his will”; rather, “they impose themselves on people’s attention almost with a will of their own.” Stimuli that can trigger these reactions include “a frightening noise” or “an abrupt alarm that threatens danger.”

According to Epictetus, “the mind even of a wise man is inevitably shaken a little, blanches and recoils…because certain irrational reflexes forestall the action of the rational mind” (Fragment 9). Similarly, Marcus Aurelius describes being “jarred, unavoidably, by circumstances” (Book 6.11).

Affected but Unmastered by Emotion

A closer look at Stoic principles reveals that emotional reactions—even so-called “irrational” emotions—are unavoidable. The Stoics often write of having emotional reactions but not being mastered by them. The practitioner of Stoicism keeps his or her head in the midst of strong emotion. Being unmastered by emotions includes:

- Maintaining control over your actions. You feel the emotion but don’t let it dictate what you do.

- Examining the basis for the emotional reaction. You challenge the beliefs and assumptions that drive your emotions, such that your feelings are brought more in line with your rational mind. As Epictetus describes, Stoics are quick to regain their composure after an upset by looking more carefully at the cause of emotion (Fragment 9).

- Keeping perspective on the emotion. Rather than being carried away by emotion, you’re able to view it with some detachment as an experience you’re having and not something that you completely identify with. In a very real way, emotions are one of those "forces outside your control" that doesn't have to dictate your ultimate well-being.

This last point is a crucial one. As Marcus Aurelius writes, “Things have no hold on the soul. They stand there unmoving, outside it” (Book 4.3). This principle can be applied even to one’s emotional experience. You can treat your automatic emotional reaction as an event that need not disturb your equanimity.

When you feel emotions like anger, fear, or disappointment, you can hold them lightly, observing them as they arise and pass through you.

You’re not overwhelmed or overcome by the emotion.

You don’t berate yourself for having a normal human reaction.

You don’t criticize yourself for being bad at Stoicism.

You simply notice that you're experiencing an emotional reaction.

Many dictionary definitions of "stoic" also leave room for emotional experience. Dictionary.com describes “not giving in to one’s emotions,” which acknowledges that emotions are inevitable. The Cambridge Dictionary offers a similar meaning: “determined not to complain or show your feelings,” which again describes one’s response to emotions and not the absence of emotion.

When you treat your emotions like a Stoic, an obnoxious person can ruin your minute but not your day. You may feel anxiety and choose to face your fear. You can experience jealousy without making it your partner’s problem. You might get angry and yet recognize that it’s based on faulty logic.

If you’re ready to elevate your practice of Stoicism, make more room for emotional experiences. Welcome them as yet another occurrence that you don’t entirely control. Let go of being upset about being upset. You can be less perturbed by difficult emotions. Focus on how you handle yourself in the midst of an emotional storm, rather than on trying to make the feelings go away.

Facebook image: Bricolage/Shutterstock

References

Aurelius, M. (2002). Meditations (G. Hays, Trans.). Modern Library. (Original work from c. 170-175 CE)

Epictetus (2008). Discourses and selected writings (R. Dobbin, Ed. & Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work from early second century CE)

Seneca (1969). Letters from a Stoic (R. Campbell, Trans.). Penguin. (Original work from first century CE)