Embarrassment

Is Shame Good or Bad? The Effects of Shame and Guilt

People get stuck in self-defeating patterns for good reason

Posted June 30, 2021 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Shame is a social emotion, triggered by having done something, even privately, that violates a social norm or perceived expectation.

- Mild shame is normal but "core shame" disrupts emotional regulation and the development of a secure sense of oneself in relation to others.

- Shaming conveys the message "What is wrong with you?" and can be transmitted through overly critical, unresponsive, or authoritarian parenting.

- Shame can be projected onto children unwittingly through parents' own history of unprocessed abuse and trauma.

Shame is hard to capture and define but, “like a subatomic particle,” it makes its presence known by the vestiges it leaves behind—manifesting invisibly as the need to shrink away, escape or disappear (Lewis, 1995; Lewis, 1971). It has the power to pull you into it like quicksand, overriding any other sense of yourself and activating a freeze reaction from the parasympathetic nervous system that blocks the flow of other feelings (Lyon, 2017; Van Vliet, 2010).

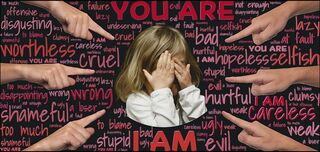

Shame is an exquisitely painful self-conscious feeling of being exposed and humiliated in the eyes of others (real or imagined) that leads to avoidance and hiding. “There is something wrong with me.” “I am a failure, a worthless human being.” “I am weak, pathetic, a loser.” “I shouldn’t have been born.” These are the hallmarks of deep, longstanding shame. It is associated with depression, anxiety (Lyon, 2017) and other psychological symptoms that operate as an unconscious defense against being aware of shame, and/or are part of its aftermath.

Shame is a social emotion (Cozolino, 2014) triggered by having done something, even privately, that violates a social norm or perceived expectation (Lyon, 2017) and leaves a deep sense of rejection and alienation that feels deserved and often lines up with an internal self-perception. This can be seen, for example, with addictions and self-destructive behavior. The need to escape the feeling of shame typically drives such compulsions to begin with; succumbing to them evokes more shame, which validates the feeling, resulting in a self-fulfilling prophecy that unconsciously “hits the spot.” (Check out my next post for practical neuroscience based tools on how to escape the escape cycle of shame and self-destructive behavior.) 10 Ways to Stop the Spiral of Self-Destructive Behaviors and Shame

How Is Shame Different from Guilt and Potentially More Harmful?

Shame is different from guilt, which is a more circumscribed feeling of conscience about a behavior—“I did a bad or wrong thing”—versus shame, which is a feeling about the self and defines who you are as a person—“I am bad or wrong.” Shame and guilt are both triggered by going against one’s values or standards, and the two can co-exist (Lyon, 2017). But guilt, with its more outward and limited focus on the negative impact on the other person, can spark positive change and healing by motivating action to make amends (Kammerer, 2019).

Shame, on the other hand, involves an increasingly inward focus on the self, loss of perspective, and negative spiraling descent into oneself (Kammerer, 2019). In this case, what you did exposed who you are —making it irreversible and irreparable and creating the need to escape but providing no way out.

The Difference between Normal and Harmful Shame

Children naturally experience shame as toddlers, when their mobility, curiosity and excitement is met with a negative reaction, shattering their newfound sense of omnipotence and replacing it with shame. Mild shame in children, resulting from parents setting expectations and limits around a behavior in the form of clear reprimands and saying “no,” is part of socialization.

This type of mild shame and guilt is not harmful, and forms the basis for the development of conscience, empathy, and the ability to inhibit impulses (de Hooge, Breugelmans & Zeelenberg, 2008) when it occurs in a context of generally responsive parenting. A “good enough” parent is mostly attuned to the child’s emotional state, repairing the attachment bond when it’s broken, restoring self-esteem and connection. Repeated experiences like this allow the child to internalize emotional regulation, as well as a sense of security and trust in themselves and others, rather than shame, fear, insecurity, and disconnection (Cozolino, 2020).

Harmful Shame: What Causes the Deep Shame that Persists in Adulthood?

“Core shame” (Cozolino, 2020) or “toxic shame”—a term coined by Sylvan Tomkins— results from adverse experiences in childhood, or later traumatic events, that create an internalized sense of self as unlovable, unworthy and bad.

This shame persists in adulthood, often in a dissociated form, emerging in its own orbit when similar feelings are evoked.

What Is “Shaming”?

Shaming children creates shame. Shaming occurs in an atmosphere that children experience as rejecting. Shaming means conveying directly or indirectly the message: “What is wrong with you?” — putting children down and criticizing them. The message can be transmitted in various ways, often unintentionally, in a climate that is harsh, controlling, or judgmental. This is consistent with authoritarian parenting styles.

Shame is also caused by physical, sexual, and other emotional abuse, as well as by lack of emotional responsiveness, disconnection, and abandonment, which are experienced by children as rejection and psychological annihilation (Cozolino, 2020).

Intergenerational Transmission of Shame: How Does This Happen?

Abuse and trauma create shame through the experience of oneself as powerless, weak, at fault or complicit. This may involve taking on as part of the self disowned feelings of badness that rightfully belong to the parent but are projected onto the child, shaming and then blaming the child for what they themselves are doing—allowing parents to escape their own feelings of shame. Unconsciously outsourcing (and acting out) their own experiences from the past, parents fail to notice or “recognize” the child and create confusion about who’s doing what to whom.

In these ways, abuse disrupts the integrity of the development of the self, creating a shame-based experience of self that consists of emotional and visceral memories. These powerful feeling memories are experienced as the “real” self, though actually a symptom of emotional trauma.

The destructive power of shame begins with being taken over by these internalized experiences and confusing this altered state of mind or visceral memory with one’s identity. Often a shame cycle ensues, beginning with withdrawal into oneself, leading to a closed feedback loop that obstructs positive growth or movement. This increases shame and the need to escape, setting up a self-perpetuating destructive cycle. It is no wonder that shame is often the hidden culprit behind self-destructive behaviors, addictions, rage and social avoidance.

References

Cozolino, L. (2014). The neuroscience of human relationships (2nd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Cozolino, L. 2020. The Power of Core Shame. https://www.drloucozolino.com/the-social-brain-1/the-power-of-core-shame

de Hooge, I. E., Breugelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2008). Not so ugly after all: When shame acts as a commitment device. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 933–943. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0011991

Dearing, R. L., & Tangney, J. P. (Eds.). (2011). Shame in the therapy hour. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12326-000

Hulstrand, K. L. (2015). Shame --- the Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Therapist Perspectives. Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers. 458. https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_mstrp/458

Kammerer, A. (2019, August 9) The scientific underpinnings and impacts of shame. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-scientific-underpinnings-and-impacts-of-shame/

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58(3), 419–438.

Lewis, M. (1995). Shame the exposed self (p.34). New York, NY: The Free Press.

Lewis, M. (2003). The Role of the Self in Shame. Social Research, 70(4), 1181-1204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971966

Lyon, B. (2017, August 21). Shame guilt and trauma. Center for Healing Shame. https://healingshame.com/articles/2017/8/21/shame-and-trauma

Van Vliet, K.J. (2010, March 18). Shame and avoidance in trauma. In: Martz E. (eds). Trauma Rehabilitation After War and Conflict. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5722-1_11