Philosophy

Is Physics All There Is?

There is more to the world than just matter and energy.

Posted June 22, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

A recent interview with the well-known physicist Sean Carroll on “the physics of consciousness” gives us a great example of a reductive physicalist view of consciousness and the world around us.

In it, Carroll acknowledges that things like cats, basketball games, and consciousness exist in so far as they are “useful categories” for us to talk about in order to make sense of our world. However, he does not think they are “fundamentally real.” Instead, he thinks only the laws of physics and the particles in the Standard Model are fundamentally real. Regarding consciousness, Carroll explains that he does not think “there's any special mental realm of existence…it's all the physical world.”

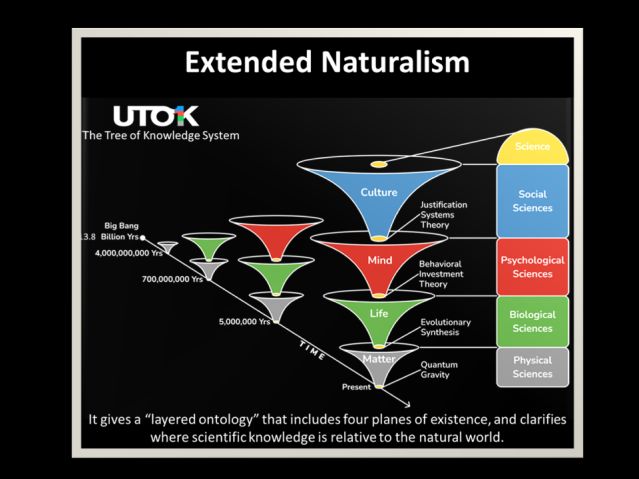

Ever since the scientific enlightenment, philosophers and scientists have had a hard time obtaining the right model that aligns the insights of physics with human consciousness and the rest of the world. According to the Unified Theory of Knowledge, UTOK, this failure is called the Enlightenment Gap. It refers to our inability to generate a coherent understanding that places mind in relationship to matter and scientific knowing in relationship to subjective and social knowing.

In the most recent Cognitive Science Show series, Transcendent Naturalism (TN), John Vervaeke and I lay out a new worldview that allows us to resolve the Enlightenment Gap. TN is grounded in a scientific-philosophical approach called Extended Naturalism. It provides us with a better, much more coherent ontology (i.e., theory of what is real) than reductive physicalism. (It also does a better job of making sense of the world than other alternatives, such as idealism or panpsychism, but that is for another post).

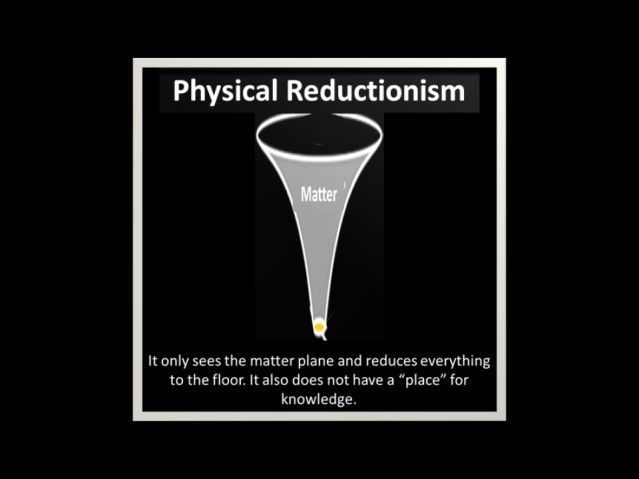

A reductive physicalist ontology is “flat.” As captured by Sean Carroll's description, it only considers the bottom of the layers of nature to be truly real. As John Vervaeke demonstrates in his excellent talk at last year’s UTOK Consilience Conference, Leveling Up, there are many reasons why that a flat ontology is philosophically misguided. Here I will only focus on one key aspect, which shows why a flat ontology misconstrues “reality” for that which is continuous and most widely shared.

Why might folks like Sean Carroll make the claim that only the bottom layer is real? Well, it is the case that the bottom level is the most generalizable. Consider, for example, that cats, consciousness, and stars are all made up of the particles and forces in the Standard Model of elementary particle physics. It is only a short step from this to saying this is the only layer that “really” exists.

Unfortunately, however, there are two problems when you conflate that which is most generalizable with that which is fundamentally real. First, there is the problem of failing to complete the reduction. You see, if we follow what modern physics tells us, all the laws and particles and space and time ultimately collapse into a singular, energy-information superforce at the time of the Big Bang. That is, the particles and laws of physics emerge from a singular superforce in a way that parallels the way life and mind emerges from more basic arrangements. So, to be genuinely consistent on this front, Carroll would have to acknowledge that the the particles in the Standard Model and the laws associated with the fundamental forces are also “useful ways of talking” about an even more fundamental, singular superforce.

To be consistent, he should have just said: “Everything is really just one thing, the same thing, the singular energy superforce that simultaneously is everything and causes everything to be. We can talk about things as being different because it is useful. That is, the Standard Theory of elementary particle physics, chemistry, biology, and psychology all give us useful categories, but they are not real in a fundamental way.”

I am guessing that something feels off to you here. One obvious problem with it is that the claim doesn’t allow you to make sense of the world in any way. By collapsing everything into one singular thing, there is no intelligible way to understand reality.

This point is a nice way of illustrating the error of equating that which is most generalizable with that which is fundamentally real. As John Vervaeke points out in his talk, to map the real world we need to understand both the generalizable similarities and the things that create differentiation. The differences are not illusions or epiphenomena, but they are part of the real world and have real ontological status.

A common term for understanding differentiation is emergence. Extended naturalism gives us a coherent way for understanding emergence. Emergence does come up in the interview with Carroll. When asked about it, he gave the example that the fluidity of the air is an emergent property that is not associated with the specific molecules that make it up. This is what we call aggregate emergence; however, it is only one kind of emergence, and it is the least interesting.

As Tyler Volk and I note, there are (at least) two other kinds of emergence, and both have more ontological significance than aggregate emergence. A second kind of emergence is when parts come together to form a new, functional wholes. An example is when an electron and a proton combine to form a hydrogen atom. As Erik Hoel demonstrates in The World Behind the World: Consciousness, Free Will, and the Limits of Science, it has been mathematically shown that emergent wholes have unique properties and causal powers that cannot be reduced to the levels beneath them.

Emergent naturalism identifies yet another kind of emergence, called “dimensional” emergence. This is when a new “plane of existence” is generated. Looking back on the history of the cosmos, four dimensions or planes of existence have emerged. First, the Matter-Object plane emerged out of the Energy-Information Implicate Order at the time of the Big Bang. Second, the Life-Organism plane emerged about 4 billion years ago. Third, the Mind-Animal Plane emerged at the time of the Cambrian Explosion, which was about half a billion years ago. And fourth, the Culture-Person plane emerged during the last half million years. Why are these different planes of existence? Because they are complex adaptive systems that are connected via novel information processing and communication networks that have real causal consequences that are not reducible to the fundamental laws of physics.

These are complicated concepts. And, in the Carroll interview, it is not always clear exactly what is being conveyed. Thankfully, extended naturalism comes with a visual depiction called the Tree of Knowledge System.

We can compare this to the picture of reality given by physical reductionism, which only sees aggregates of emergence and only considers the basement to be what is fundamentally real.

To see if we really disagree, we need to check with Carroll to see which one of these representations align with his understanding. I bring this up because I have had folks who initially identify as reductive physicalists and look at the Tree of Knowledge and say it aligns with what they are trying to say. So, much of the misunderstanding might stem from us having an inadequate language to describe the territory rather than more fundamental disagreements about the nature of reality.

The natural sciences have revealed that there is a deep ontological continuity that stretches from this current moment back to the energy-information singularity that started it all. However, this fundamental starting point is not the only thing that is real. Thankfully, via extended naturalism depicted by the ToK System, we now have a coherent, naturalistic ontology that specifies both how nature is continuous and how it is differentiated, and how we have obtained real scientific knowledge of us, the energy information superforce, and the reality in between.