Cognition

What Is the Relationship Between Psychology and the Psyche?

Here's why the psyche should be separated from scientific psychology.

Posted February 26, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Although they are related, the psyche should be separated from the science of psychology.

- The science of psychology should be defined as the science of minded behavior.

- The psyche should refer to the unique, subjective experience of being in the world.

- Here are some new ideas for how to put them in proper relation to each other.

How does the concept of the psyche relate to scientific psychology?

This post describes a new way of framing these two concepts.

If we trace the origin of the word psychology, we find its root in the term psyche, which comes from Aristotle. It roughly translates into soul. Despite this historical connection, the psyche does not feature prominently in modern scientific psychology. Virtually none of my professors in college regularly used the word “psyche,” nor did I see it in textbooks. Instead, behavior, mind, and cognition are the primary core concepts that characterize the science.

My book, A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap1, makes the case that we can develop a coherent science of psychology by defining it as the science of minded behavior. In the final chapter, the book explains why the concept of the psyche is an important and useful construct but not one that is scientific.

To understand the argument, we first need to understand the nature of modern science. In his excellent book, The Knowledge Machine2, Michael Strevens lays out the case that science produces knowledge by following what he calls the “iron rule of explanation,” which is defined as follows:

The rule that all scientific arguments be settled by empirical testing, along with the elaborations that give the demand its distinctive content: a definition of empirical testing in terms of shallow causal explanation, a definition of official scientific argument as opposed to informal or private reasoning, and the exclusion of all subjective considerations from the official scientific argument.

This is highly consistent with how I characterize scientific methodology and knowledge production in A New Synthesis. In addition to considering the methods of science, I also tackle the question of the picture of knowledge that science has generated about our place in the universe. I argue that there is a general consensus that can be characterized as a “Big History” picture of scientific knowledge. Specifically, virtually all who grapple with what science has revealed about the universe place that knowledge on the axes of time and complexity3. This is the idea that there has been a process of cosmic evolution across billions of years, from relatively simple particles into atoms into molecules into cells and, ultimately, into human beings.

It is against this backdrop that we encounter the problem that frames my life’s work. This is what I call the problem of psychology4. The problem of psychology refers to the fact that the science of psychology is never coherently defined. That is, unlike biology, which is crisply defined as the science of life, the science of psychology lacks any clear definition that specifies the thing in the world that it is about.

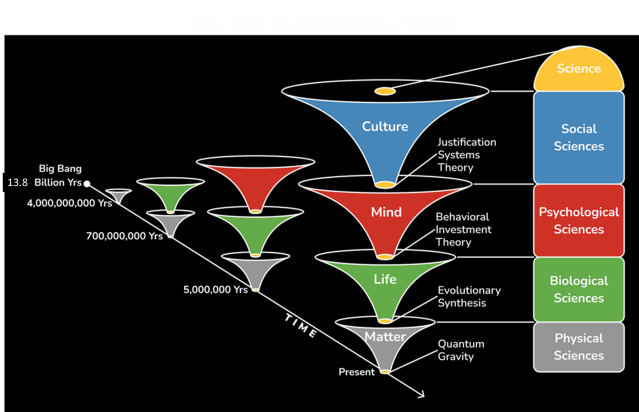

UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge5, purports to be the first system of understanding that solves the problem of how to effectively define scientific psychology. It does so via a new map of Big History called the Tree of Knowledge (ToK) System. The ToK System shows how to divide the universe into five different orders of nature.

First, there is an Energy-Information order that exists prior to the Big Bang. Then, through the Big Bang phase transition which happened about 13.8 billion years ago, the Matter-Object dimension emerges. Following that, the Life-Organism dimension emerged about four billion years ago. Then, the Mind-Animal dimension emerged approximately 550,000,000 years ago. Finally, the Culture-Person plane of existence emerged between 500,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Crucially, each of these planes of existence is characterized by specific behavior patterns: The Matter-Object plane is characterized by material behavior; the Life-Organism plane is characterized by living behavior; the Mind-Animal plane is characterized by minded behavior; and the Culture-Person plane is characterized by cultural behavior. This is important because observing behavior is central to the language game of science. Indeed, via the ToK System, UTOK places science in the Culture-Person plane and characterizes it as a special kind of justification system, one based on observing behavioral frequencies and generating descriptions and explanations for them, just as Strevens argues.

Ultimately, this means that, with the ToK System, we can now link up the major domains of science with the different dimensions of behavior. For example, we can clearly align the physical sciences with the Matter-Object dimension and the biological sciences with the Life-Organism dimension. This allows us to see what the core of psychological science should be about: minded behavior patterns. These patterns encompass the functional awareness and responsivity of animals, mediated by their brains and complex active bodies. Moreover, with its division between Mind-Animal and Culture-Person behavior patterns, the ToK helps us see how why human psychology should be a separate branch of psychology that serves as the bridge into and base for the social sciences.

If psychology is the science of minded behavior, what, then, is the psyche?

If you look in the dictionary, you will see that it ambiguously refers to either the human mind or soul. In UTOK, the definition is more specific. The psyche refers to your unique, particular, qualitative pattern of experiencing and knowing about yourself and the world. In other words, the psyche is fully subjective.

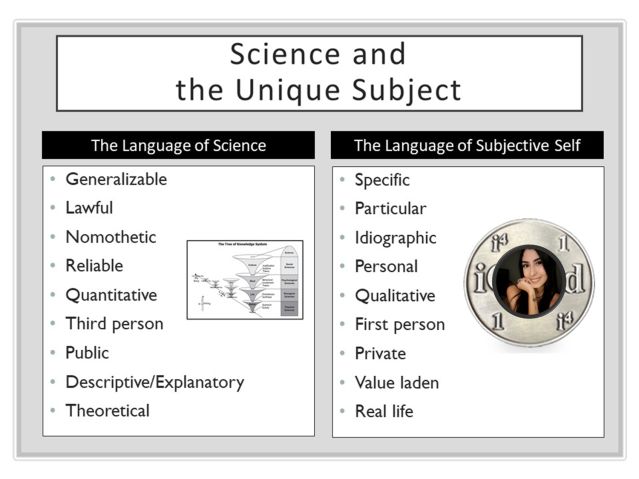

With this conception of the psyche, let’s return to Strevens’s characterization of science in terms of the iron law of explanation. It shows that scientific knowledge is very much about trying to eliminate subjective knowledge. This makes the point that the language of science does not mesh with the language of the subject. My guess is that for those who have been trained as natural scientists, this conclusion is not too surprising. However, it does help us see why psychology has struggled so profoundly with achieving coherence as a natural science.

This analysis also shows that we have been lacking the right conceptual grammar for framing the relationship between the language of science with the language of the subject. UTOK provides us a way forward here. First, as we have seen, UTOK defines the science of psychology as the science of minded behavior and shows what this means with the ToK System.

Second, it brackets off the language of the subject from the language of science and defines subjective knowledge as unique, particular, specific, local, and qualitative. Doing this identifies a need to frame subjective knowing. To address this need, UTOK gives us a novel idea called the iQuad Coin. Space limitations prevent me from diving into the specifics of the iQuad Coin here6. I will simply state that it provides the “placeholder” for your specific, unique, particular psyche, and it is designed in a way that makes “associative identities” with knowledge in physics, philosophy, and mathematics7.

In sum, up until this point, we have lacked a clear way to define the psyche (or soul) in relationship to scientific psychology. UTOK is a game-changer in this regard. With its ToK System and iQuad Coin, UTOK allows us to clearly define both the science of psychology as the science of minded behavior and the psyche as the unique experience of the subject in the world and place them in proper relation to each other.

References

1. Henriques, G. (2022). A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan. Henriques, G. (2022). A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan.

2. Strevens, M. (2020). The knowledge machine: How irrationality created modern science. Liveright publishing.

3. Henriques, G. (2022). A new and better map of Big History. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 155-184). Palgrave Macmillan.

4. Henriques, G. (2022). Psychology, we have a problem. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 9-28). Palgrave Macmillan.

5. Henriques, G. (2022). The Unified Theory of Knowledge: A new metapsychology for the twenty-first century. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 57-85). Palgrave Macmillan.

6. Henriques, G. (2022). The basics of the iQuad Coin. Unified Theory of Knowledge Blog on Medium.

7. Henriques, G. (2023). Are you an MP3 player? Learning to play the iQuad Coin at an advanced level. Unified Theory of Knowledge Blog on Medium.