‘Empathy’ has been revered as the emotional analog of wisdom. I’m here to say that it is vastly overrated, and there is something else far better. More on that later. Empathy is variously defined as “The feeling that you understand and share another person’s experience and emotions; the ability to share someone else’s feelings.” (Merriam-Webster), ‘the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.’ (Oxford Dictionary); ‘The projection of one's own personality into the personality of another in order to understand the person better; ability to share in another's emotions, thoughts, or feelings.’(Your Dictionary). It is an imaginative projection of one’s own consciousness on another person.

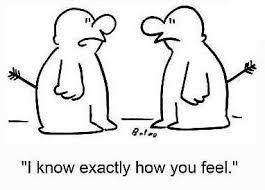

Empathy is commonly understood to mean, ‘I know exactly how you feel because I have felt the same way myself.’; ‘To understand someone you have to walk a mile in their shoes’. Here’s the problem – it seems to sound caring if you say, ‘Your mother died. I know exactly how you feel because my mother died too.’ However, what commonly follows is ‘Let me tell you about my mother’s death’, as if this is supposed to be comforting. ‘Let me tell you about my favorite subject - me.’ Try saying this to someone and see how well it is received. A person in mourning needs to be listened to. We need to be receptive.

In reality, empathy is actually - projective self involvement. This is ultimately a form of narcissism that passes as caring. The real caring item is best described as ‘Responsiveness’. Responsiveness is a process of emotional receptivity, by which one is directly tuned into and involved with the other person with no reference to oneself at all. It does not involve identifying with the other person. It is a form of resonance with feeling itself. This capacity and its origins all come from maternal love. [see – "What is Love?"] The mother responds directly to her baby’s needs without any reference to herself. She is and always was, tuned into to the baby’s physical and emotional states directly. This is the source of all love. As a psychotherapist, the issue in therapy is responsiveness, not empathy.

In fact neuroscientists have a theory which demonstrates how empathy and responsiveness are very different. They propose that so-called empathy is the result of the activation of mirror neurons. This is supposed to explain how mirroring allows one to read the emotions in others as if it is in one’s self. This then is said to determine our emotional sharing ability. In contrast, as I show in the "What is Love?" blog, responsiveness is built in from the beginning of a pregnancy from the mother to the child. It is in place at birth, and continues and matures all the way to the creation of consciousness at six weeks old. The connection of feeling between the baby and the mother is a mutual loving responsiveness when gets established and continues for the rest of their lives. It has no reference to projective identification states. This resonance of feeling is the source of all loving and is the real item.

In psychotherapy, the emotional holding that is necessary to foster mourning the pain of past traumas takes place exclusively in the realm of responsiveness – direct feeling for the other person –feelings given and feelings received. As a young therapist I prided myself in my ability to understand my patients because I felt I had a relatively broad base of experience, and I could identify with their plight through empathy and sensitivity. But unfortunately, I was barking up the wrong tree. Here is what happened. Janice arrived on the inpatient ward and was assigned to me. She had overdosed when her brutal ex-husband had threatened her once again and was heading to her apartment for a confrontation. In fear and despair, she overdosed. She had no money, and her ex-husband was not paying the alimony or any child support. This was her story. I met with her in therapy for a couple of weeks. I felt for her as a victim. I was empathic for her plight. I understood. I felt like a good psychiatrist, sensitive to her needs and pain.

A couple of weeks later, we were meeting for our regular therapy session. She began the session. “Sorry about this, but Dr. X, the chief resident, told me you would fill out the food stamps form. Okay? Here it is.” She explained that early in her hospitalization, my chief resident had arranged to get her on food stamps to feed her three-year-old child. I hadn’t known anything about it. When Janice approached him to renew the food stamps, he told her to finalize the application with me. I responded that our relationship would just deal with therapy, and I wouldn’t be involved in getting her or denying her money. If she wanted food stamps, she should go back to Dr. X. At first she got angry and accused me of not caring about her hungry baby. “It’s not a big deal. Just sign the form!” Her aggressiveness began to ring funny to me. I continued to draw the line until, to my surprise she suddenly changed her tune. “Dr. X is a self-important fool! Here’s the real story. My ex-husband was coming over for dinner ...”

“Huh? I thought he was a monster.”

“Well, actually, he comes to dinner several nights a week.”

“He does?”

“Um, we’ve been doing that for a while. He sees the baby and, you know, it’s good for her to see her father …”

“This isn’t adding up right.”

“Okay, here’s the real truth. We got divorced to qualify for housing assistance. They wouldn’t give us any money because we were married. My husband is a good man who works very hard and makes a good living. It’s not fair that only single mothers get assistance. The divorce was just to get money. What’s the difference? We’re still together. In fact, we live together in our apartment full time. We had had a fight about something, and I called him at work and told him that I had overdosed. Of course, I hadn’t. I knew he would come to my rescue as he always did. The problem was that he would come home and realize I hadn’t overdosed. He’d see that I had lied again, and he would really be fed up. So while he was on his way home, I had to force myself to swallow enough pills, and time it right that he would find me unconscious. Sure enough, it worked. He found me, called the medics, and here I am.”

I certainly didn’t see this coming. But it effectively taught me to listen, pay attention, and not assume I understood. Once I got myself out of the way, I was free to listen, pay attention, be open, and be responsive to Janice’s actual play of character. The therapist has to be open to learning about his patient’s characterological world, wherever this takes him. This means a willingness to be open to whatever is stirred up in himself—the full range of human experience, identities, and feelings. This ranges from the sublime and tender to the dark forces of horror, terror, depravity, and cruelty. The therapist must genuinely be willing to sit with aspects of all of these forces, anything stirred in him, in order to sit with his patients’ characterological dramas and explore them.

I learned that therapy is not about empathy but responsiveness. If it were the otherwise, I would only be able to treat people who were just like me. I couldn’t treat a female, or a person of a different race, ethnic background, religion, or temperament. I couldn’t treat someone of a different age, culture, or language. I would have to have the same sexuality or the same alcohol or drug history as a given patient. If we take identity likeness all the way, then the only person I could treat would be myself. There is a whole world out there, most of which is outside my personal experience. It opened me to the whole gamut of human experience. So I was open to learn. We are all cut from the same cloth and the human story is one story. And we all can imagine and identify with anything, once you get past that no one is better or worse than someone else. Of course, we need to be open. Of course we need to listen. Of course we need to be sensitive to differences. As a therapist, I must be open to working with the full scope of all characterological plays, including all imaginable aspects of the dark side, the source of suffering.

Sometimes it may be functional that in organizations such as AA, it can certainly be helpful to have others share in the same experience and to know what it is like. “I’ve been there.” In this case the projective identification fits. People agree to take turns to tell their story. In this way one person doesn’t hog the spotlight. Alcoholics know all the tricks. It is useful because as they say, you can’t con a con. AA is indeed useful for many people to stop drinking. And that certainly is good. But in my experience, to really deal with one’s character, projective self identification can only go so far. One really has to reopen the real human need and its associated pain. This can only happen in the context of trust in a loving responsiveness for the very feeling of one’s being. To reopen something that has been closed off due to trauma, is the hardest thing on earth.

The idea that there could be a quick fix for a patient’s suffering is an absurdity. The necessary time for digesting one’s pain reflects the nature and degree of damage that created one’s characterological drama in the first place. The time for recovery reflects the damage done in one’s world. Therapy takes how ever long it takes. Let’s say you were baking a cake that took fifty minutes at 350 degrees, but you decided you wanted it in ten minutes instead of fifty. Here’s an idea: Why not cook it at 1750 degrees for ten minutes? Sounds like a plan—the only problem is, you’ll get soot. It cannot work. You cannot override Mother Nature. There are no shortcuts. Short term therapy, no matter what it promises cannot deal with the real issues. Cognitive therapy cannot deal with the real issues which are feeling issues, and do not lend themselves to cognition. And certainly psychiatric problems are not biochemical abnormalities, as if drugs could possibly deal with what ails us. All of our problems are human problems that reflect our human story.

Robert A. Berezin, MD is the author of “Psychotherapy of Character, the Play of Consciousness in the Theater of the Brain”