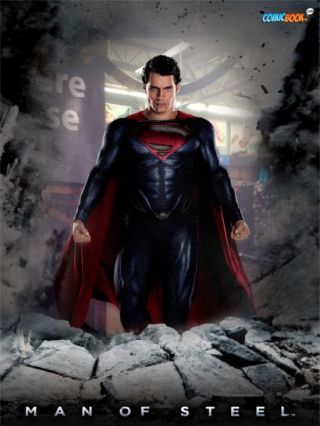

Man of Steel

I like Superman—as a character, as a superhero, as an embodiment of (certain) values. I had looked forward to seeing Man of Steel. Although I was disappointed (more on that later), I’ll start with what I liked. Warning: I’m assuming that readers have a basic knowledge of Superman’s origin story. I discuss some details of the film, so you may want to see the film before reading this review.

First, I liked this incarnation of the “villain” of Zod. In What Is a Superhero?, I have an essay on the typology of supervillains (“Sorting out Villainy”). According to my classification scheme, Zod is a heroic villain. His actions are motivated by—what is to him—an altruistic cause (saving Krypton/Kryptonians). This is made explicit at the beginning of the film, when Zod says to Jor-El (Superman’s father) that he’s taken up the sword against his own people for a greater good. Jor-El, too, could be considered a heroic villain in that he’s done something against Kryptonian law, but is doing so for what he believes is a greater good. The importance of point-of-view in defining “good” versus “evil” is nicely portrayed. It’s not a “black and white” morality tale.

Second, I like the way the film (accurately) portrayed the social challenge of being gifted (i.e., “super”). Like many superheroes, gifted children in our world sometime hide their talents and abilities from others for fear of social ostracism or harassment. (In Clark Kent’s case, though, it was because the government might want to “take” him.) Like some gifted people in our world, the young Clark views his budding powers as burdens—to be hidden. Clark’s father explains that one day he’ll view his abilities as gifts, not burdens. This is also true for gifted people in our world. (For more about the ways that superheroes are similar to and different from gifted individuals, see my essay with psychologist Ellen Winner, “Are Superheroes Just SuperGifted?” in Our Superheroes, Ourselves.)

Third, this version of Lois Lane is the best screen version thus far. She’s smart and spunky but not high strung or temperamental. It’s easy to see why Clark would like her (which isn’t true of the Loises in the other films). She’s an admirable character. Way to go!

The aspects of the film that I didn’t like were, unfortunately, numerous. One fundamental flaw rests on the reason for Jor-El and Lara trying to conceive “naturally” on Krypton: To bring a child into the world that wasn’t pre-conceived or pre-programmed with a destiny. (On this version of Krypton, it seems that children’s DNA is genetically engineered to fill society’s niches—soldier, scientist, etc.—and fetuses are externally incubated.) Yet the young adult Clark, on Earth, discovers a holographic-type projection of his long-dead father, and this Jor-El tells Clark what Clark’s destiny is—why he was sent to Earth!! He’s “supposed to guide humans, to be a force for good. You will help them to accomplish wonders.” This hypocritical stance about destiny versus free choice is a major plot flaw, in my mind.

Another significant problem with the plot rests on the idea that humans would freak out if they knew an alien lived among us. Yet by the end of the film, after downtown Metropolis has been practically laid waste by aliens, there is no sense that humans are freaking out about Superman being an alien, or even freaking out that there was an alien battle on Earth. This basic fear of people’s response to knowing about aliens, which drives much of story of Clark’s childhood, is carelessly thrown off by the end of the film.

And then there is the wanton destruction, the endless fight scenes, explosions, buildings collapsing. It became boring. I couldn’t help but notice that the Daily Planet building took its share of damage, yet by the end of the film, the Planet’s office looks fine, and there no sense of the trauma that Metropolis’s citizens must have experienced since their city was a center ring in which the aliens fought. And the city is magically clean and rebuilt by the end! Yes, we have to suspend disbelief in most superhero films (perhaps Christopher Nolan’s Batman films being the exception), but not this much.

The film was called Man of Steel, but it felt that too little of the film was actually about Superman. It was really about Jor-El versus Zod, with Superman acting as proxy for Jor-El. I wanted to see more character development about the adult Clark/Superman. In a film over two hours long, it seemed that his screen time—when he wasn’t in a fight scene—was too brief, totaling perhaps 20 minutes. (If you were to time it, it’s possible that there was more screen time on this. But it felt too brief and his “character development” superficial.)

This contrasts dramatically with the Nolan Batman films. Which is ironic because the script was written by the same folks who wrote Batman Begins: Jonathan Nolan and David Goyer. Whereas Batman Begins provides wonderful and psychologically insightful character development, Man of Steel does not.

References:

Rosenberg, R. S. (2013). Sorting out villainy: A typology of villains and their effects on superheroes. In R. S. Rosenberg & P. Coogan (Eds). What is a Superhero? New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenberg, R. S., and Winner, E. (2013). Are superheroes just supergifted? In R. S. Rosenberg (Ed). Our Superheroes, Ourselves. New York: Oxford University Press.

Copyright 2013 by Robin S. Rosenberg.

Robin S. Rosenberg, Ph.D., ABPP is a clinical psychologist in private practice in San Francisco and Menlo Park, Calif. She often writes about the psychology of superheroes. Her latest books are What Is a Superhero? and Our Superheroes, Ourselves. Her website is www.DrRobinRosenberg.com.