Health

The Price of Air

The cost of breathing just went up.

Posted April 12, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

The cost of breathing increased in the last month.

In the science fiction film Total Recall, a hapless Mars colonist remarks that the authorities are thinking of “raising the price of air.”

That's what's happened to us. The price increase takes different forms:

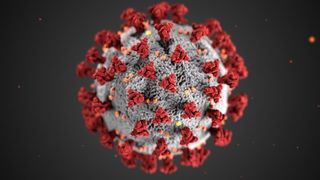

A. Breath and life. Breathing means life. Many cultures speak of “the breath” with awe. If you’re infected with Sars Cov 2 (and many of the infected are asymptomatic and don’t know it) you can infect your children or your parents, your friends or co-workers.

You can’t say goodbye to people in ICUs. You can’t go to funerals. My sister attended the virtual funeral of her mother-in-law, who she dearly loved. She could not be there. It was all strange.

What’s gives life can now make others ill. There’s always been a health “cost” to breathing. We spew out all kinds of viruses and bacteria when we breathe and speak, cough and gasp. But the direct price has gone up. The psychological price is heavy. Our normal world is no longer safe.

B. Pollution. More polluted air, filled with particles from cars, ships, airplanes and industry, was never good for people’s health, no matter how prized by certain political leaders and economists. Yet it’s clear that Sars Cov-2 spreads more readily in cities blanketed with higher levels of microscopic particles.

Are the viral particles piggybacking on the pollutants? Are the pollutants in some ways diminishing the immune response that counters the virus?

At this point we don’t know. But now we recognize that polluted air does not just increase lung cancer and chronic obstructive lung disease. It helps spread Covid-19, which means the air we breathe has another, more intimate health dimension. That’s something to consider when we revamp our energy policies after this pandemic.

C. The ability to move. It’s said that you and I periodically breathe the same air particles that Aristotle, Plato, and Michelangelo inhaled. That does not make us geniuses, but it does speak to “breath” as the spark of genius, as the foundation of spirit.

But air has also always carried infectious particles; malaria means “bad air,” though the disease itself transmits differently. Yet now that air carries danger, we need to transport ourselves differently, including in ways we thought were safe.

Public transport is now a different animal: Do subway poles make you sick? Does breathing the air of that fellow who just walked into the Metro set you up for Covid-19?

What about walking, biking, and running? Respiratory droplets and microaerosols are thought to be the main way the disease spreads. They are expelled more readily when you run or bike. One Belgian-Dutch study – not peer-reviewed — argues that bicyclists create a “slipstream” with the greatest number of particles appearing just behind. Yet that’s how many of us bike. And these researchers argue that you should not be 6 feet away, but 20 feet or more away from bikes, and pointedly not to stay directly behind a rider.

Telling bicyclists that they increasingly expel viral particles while doing healthy exercise will not win you friends. One way to handle the problem is to wear masks.

Masks can feel uncomfortable when you’re biking or running. Yet they are used routinely this way in East Asian countries with relatively good control–so far–of their epidemics.

Perhaps we will find out in a few weeks or months that biking and running out on the street are perfectly safe for everyone surrounding and following them. Except we don’t know that now. Ventilation helps, but still. So recognize that “healthy exercise” may not be healthy for everybody else. Distance accordingly. Bicyclists may want to use bike lanes where they can, rather than constantly yielding to pedestrians on sidewalks. And masks should be considered when walking outside.

Bottom Line: Air, like water, is necessary to life. Sars Cov 2 has increased the cost of air. What you breathe, I breathe. Your health affects my health, and my health yours. A pleasing, charming conversation, one of the great pleasures of life, can now invisibly and unconsciously harm.

As the yogis say, you have to pay attention to the breath.