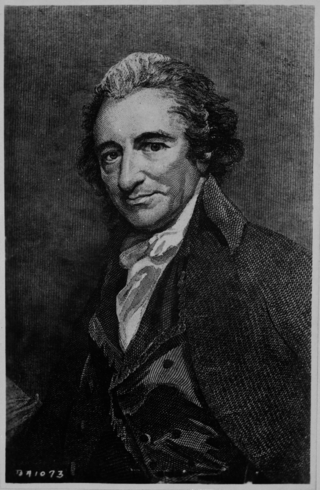

One day toward the end of 1774, Thomas Paine, a 37-year-old man with a prominent nose and genius in his eyes, took ship to America from England. He came with a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, who called him “an ingenious, worthy” young man. America was the land of opportunity for a clever person without means.

And England had beaten him down. He’d failed as a corset-maker; he’d failed as an English teacher; he’d failed as a tobacco seller; he’d failed as a customs officer and excise tax collector. His first wife had died, and he was separated from his second. Paine made his passage alone.

He landed in North America on 30 November. And in Philadelphia just over 13 months later, on 10 January 1776, he made his mark. His short pamphlet, Common Sense, came out. By the end of that year, it had gone through two dozen editions, and sold a hundred thousand copies, at least.

Common Sense was a call to arms for the butchers and bakers and candlestick makers, small farmers and shopkeepers and militia members who borrowed or bought it or thrashed it out. Americans were done with monarchy. William the Conqueror was “a French bastard landing with an armed banditti,” and “nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang;” his sitting descendant, George III, was the “Pharaoh of England,” and a “Royal Brute.” Aristocracy had run its course: “When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember that virtue is not hereditary.” And Americans were ready for a fresh start. “In this first parliament every man, by natural right will have a seat.”

Paine reinvented a political vocabulary. The res publica of Cicero’s Latin, the republic, or “public thing,” was taken out of the context of the old Roman aristocracy, and broadened to secure the freedom of all men. And the dēmokratiā, or democracy, or “rule of the people” of Aristotle’s Greek, was removed from the rabble, to include a large and equal representation.

“In the early ages of the world, according to scripture chronology, there were no kings.” Paine took some of his theory from the oldest of histories. He remembered that, on their long trek across the desert, Moses’ people lived under republics, administered by elder women and men. It was only after they got to the end of the road in Canaan, and settled down, that Saul and David were set up to rule over them. “We have added unto our sins this evil, to ask for a king.”

It was different on the ships that took Paine across the Atlantic, and on the caravans that swept across the North American continent. People kept moving around. As Common Sense famously went on,

“This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster,”

or even better,

“O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose, not only the tyranny, but the tyrant stand forth! Every spot of the old world is over-run with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted around the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her. – Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.”

Tom Paine was ahead of his time.

On 21 May 1792, a year after his follow-up essay on The Rights of Man was written in England, George III issued a Royal Proclamation Against Wicked and Seditious Writings and Publications. Paine’s publisher was sent to prison for 18 months; Paine was burned in effigy, ordered to appear in court, and found guilty in absence.

Because he’d already taken ship to revolutionary France, been elected to the National Assembly, and appointed to a committee of 9 set up to draft a French constitution. Those successes were short. On 28 December 1793, he was arrested by members of Robespierre’s faction, and locked in the Luxembourg Palace for 10 months. His head was almost cut off.

On 1 September of 1802, Thomas Jefferson offered him passage on an American warship, and Paine sailed back to the United States. But his patron was a Republican President, and he got ripped to shreds by the Federalist press. They called him a liar, an infidel, a drunk, a loathsome reptile and a demi-human archbeast, who wallowed in confusion, devastation, murder, bloodshed and rape. He died alone in New York, in 1809.

Over the centuries, poets, politicians, inventors and American airmen have commemorated Tom Paine; but he commemorated himself best. As he put it in a letter toward the end of his life: “My motive and object in all my political works, beginning with Common Sense, the first work I ever published, have been to rescue man from tyranny and false systems and false principles of government, and enable him to be free, and establish government for himself; and I have borne my share of danger in Europe and in America in every attempt I have made for this purpose.”

He’d crossed open borders, and he’d kept an open mind.

References

Foner, Philip. 1945. The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine. New York: Citadel Press.

Foner, Eric. 1976. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. New York: Oxford University Press.