Trauma

The Science Behind Trauma-Informed Yoga in Corrections

Combating the physical and mental health influences of chronic stress.

Posted September 11, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The suicide rate among correctional officers is twice that of the general population.

- Chronic stress has a debilitating influence on physical and mental wellbeing.

- Trauma-informed yoga provides a simple, yet effective approach to combatting stress.

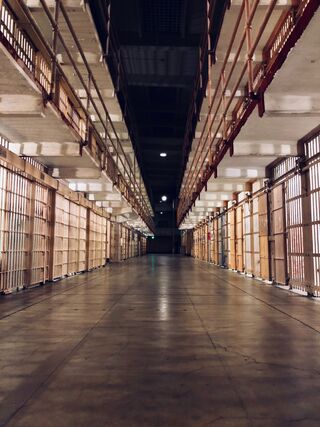

This is a follow-up post to last month’s, Yoga as a Stress-Reducer for Corrections Professionals, with licensed clinical social worker Sue Radcliffe. With a suicide rate twice that of the general population, correctional officers are at an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide, which is a significant concern for the men and women who risk their lives ensuring that the public remains safe and secure.

Radcliffe created this unique program after learning the statistics of correctional officers’ negative health outcomes, the lack of policy addressing wellness, and the fact that there were no formalized recommended wellness protocols and treatment programs that officers would voluntarily attend. According to Radcliffe, damage from stress occurs within the limbic system starting with the amygdala. The most notable features of the limbic system, as noted by Shanker (2017), are the “survival” traits such as being hypervigilant for signs of danger (auditory, visual, olfactory); fleeing or fighting at the slightest provocation; being hyper-focused; seeking a place of safety; mobilizing resources to prepare the body for intense exertion. Simply stated, it is responsible for the fight, flight, faint, and freeze reactions.

The amygdala sends a message to the hypothalamus, which is responsible for our autonomic nervous system, the sympathetic, and parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic system, as described by Radcliffe, increases your heart rate and blood pressure so that you’re ready for a threat. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for calming you down. Radcliffe goes on to further note that when the hypothalamus sends a message to the pituitary, the pituitary excretes adrenaline and cortisol to prepare officers for the threat they’re about to confront.

This is a normal reaction/response to threats; however, given the environment in which corrections officers find themselves, they are in a constant state of hypervigilance, always on alert for potential dangers. The system described above (amygdala, hypothalamus, pituitary) is essentially “stuck” and thereby constantly contributing to the officer’s relentless state of hypervigilance. Elevated levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that our bodies release in response to and in anticipation of stressful events, according to Bergland (2013), interferes with learning and memory, lowers immune function, and increases weight gain, blood pressure, cholesterol, and heart disease.

Correctional officers note emotional and behavioral changes after time on the job, and brain science can explain it all. The constant secretion of cortisol begins to “eat away” at other parts of the limbic system. When the hippocampus is “eaten,” one can have difficulty learning and remembering. Damage to the thalamus, which is our emotional relay station and in charge of how we process our senses, can cause extreme emotional reactions (or no reactions), and sensory perceptions being intensified (such as getting annoyed with sounds, hearing statements as threating or curt in tone). The frontal lobe is considered the region devoted to “executive functioning” of the brain. This is the last part of the brain to develop (around 25 to 26 years) and is responsible for things such as planning, having foresight, understanding behaviors and consequences, and impulsivity. Being able to look ahead and plan becomes challenging, and recognizing possible negative consequences of specific behaviors is challenging. Acting first and thinking later can occur. When the limbic system of the brain is impacted by excessive cortisol secretion, the correctional officer’s daily routine in life is difficult, both personally and professionally.

Our brains are not meant to be exposed to constant threats. We are meant to have a threatening circumstance but then get out of the threat into safety. For example, if you are walking across the street and see a car headed towards you, your amygdala, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland are activated and give your body the energy to run to safety. You are out of the threat and your brain can relax. As a correctional officer, you find it incredibly difficult to relax. If you relax your brain, then harm could result.

These changes in the brain can lead to correctional officer fatigue, which I addressed in a previous post, Correctional Officers and Compassion Fatigue. A practical approach to effectively addressing the negative effects of chronic stress is trauma informed yoga, which is intended to calm the brain by staying in the present moment, which leads to neurogenesis, the process through which new neurons are formed in the brain. This occurs when you are in the moment — for it gives your brain a break. In the case of trauma-informed yoga, you are “in the moment,” paying attention and being prompted by the instructor to pay attention to specific muscle groups and body parts. This calms the brain, thereby creating healing.

This may sound too good to be true, but it really is that simple. According to a study by Price et al., (2017), evidenced-based yoga practice can result in a decrease in PTSD symptoms. You can heal your brain, stretch your muscles, and decrease PTSD symptoms. If traditional treatment modalities such as talk therapy or medication management treatment are not for you, then you might want to consider trauma-informed yoga.