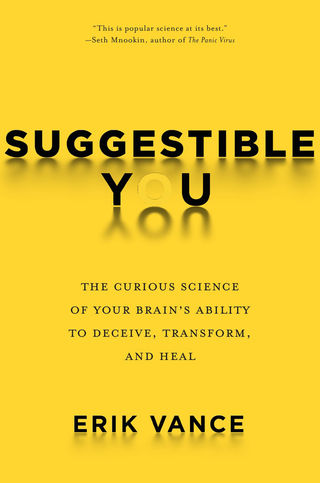

Placebo

Suggestible You

The Book Brigade talks to science journalist Erik Vance.

Posted November 3, 2016

The power of suggestion lies behind the placebo response, but let’s not kid ourselves —it plays a big role in our everyday life, too

You talk in terms of the brain tricking itself. Why call it a trick when n fact making real events fit our prior expectations is the way our brain works all the time?

I thought long and hard about the word "trick." Also the words "gullible" and even "suggestible," because they have something of a negative connotation. But in the end, that's why I like them. I want to invert the reader's own expectations a little. It is how the brain works but when expectation alters perceived experience, it feels and looks like a trick. Think of a magic trick. There's nothing unusual about a box with a slanted mirror in it; it doesn't defy any laws of nature. But when you step back and allow yourself to go along with it, sure enough, it looks like magic. A pretty good trick.

You were a toddler very sick with Legionnaires disease but your Christian Scientist parents decided to pray rather than take you to a hospital, and you recovered. How do you explain that?

Well, as I say at the end of the book, I doubt it was actually Legionnaires disease. Certainly my parents thought it was at the time, because of the news reports. Ironically, many people who contracted it during that particular outbreak did so in a hospital. But after consulting with several pediatricians, I can say that whatever it was, it was certainly a serious, life-threatening problem.

Honestly, I can't say exactly what happened. Most likely, my parents prayed the hardest when the disease was at its worst and then it ebbed naturally.

But more important is what it did to me later. That story gave me a certainty that I could harness God's power. As a kid I used to love that story because it made me feel like I almost had superpowers. And for many people, confidence and certainty are the keys to an effective placebo response. I would think about myself as a baby and imagine the power that had healed me and use that certainty to fuel my prayers about every cold or scratch or case of chicken pox I had.

How do you describe the placebo effect?

First, I add an s at the end, because there are many placebo effects. Really, it's just a term to encompass a bunch of different processes within the body that occur to make us feel better in the absence of effective treatment. Regression to the mean is its own type of placebo effect. Others really are just cases of self-delusion. But the more interesting ones for me are when the body takes proactive measures to ensure that reality matches expectation.

Does it ever change, and if do, how so? And why?

That's the frustrating thing about the placebo effect—it's always changing. From one person to another, from one day to another. When scientists try to screen out placebo responders from a given trial, new ones appear out of thin air to replace them. But what I find fascinating is how placebos differ from one disease to another. Obsessive-compulsive disorder tends to see very low placebo responses while depression can see a 60 percent change. Alzheimer's tends to be low and Parkinson's high.

To me, this screams that there is some underlying physiological principle at work here. If this was just a product of delusion, it would be the same for every condition. But such variation indicates there are chemical interactions that preferentially drive changes in certain conditions. A good starting list for those conditions would be pain, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, Parkinson's disease, and addiction.

How is the placebo response influencing the development of new drugs?

Since 2011, the 2,000 registered trials resulted in exactly five new treatments. This is largely due to the placebo effect. Oftentimes a drug that is not effective looks effective in early trials because of a placebo boost. Or else a treatment that is effective looks ineffective because of an especially high placebo response in the placebo arm. The way around this, of course, is large sample sizes to create a more accurate picture. But remember that every participant in a trial costs $30,000 to the company doing it. The result is fewer drugs coming to market and those that do being extremely expensive.

Are some people especially prone to placebo-responding?

This is the $64,000 question. Well, with inflation and the high cost of drugs, more like the $6 billion question today. Almost since the placebo effect was discovered, scientists have searched for the perfect "placebo responder." It's sort of the white whale of people who work in this area. They've looked at gender, age, hypnotizability, personality traits and, in at least one odious example, race. None have panned out. So the short answer is no. But recent genetic research has uncovered a few genes that seem to be involved in placebo responses. So if you have all these genes are you guaranteed to have a placebo response? Not necessarily. But if you take 1,000 people and give them placebo pills it appears that the people who feel better will be much more likely to have them.

What is the most intriguing fact about placebos that you discovered?

Tough call. How about this? If you give a placebo pill to a Parkinson's patient you can expect a 10 percent, maybe 15 percent, improvement in freedom of movement. If you give that same person a placebo surgery, you can expect as much as 25 percent freer movement.

What was the most intriguing personal narrative of placebo response that you heard?

Mike Pauletich, a Parkinson's patient in the Bay Area, had an incredible response to a new therapy a few years ago. He went from struggling to walk to skiing and climbing mountains within a year. Truly inspiring. But the trial failed because the placebo response was so high. Which was shocking, given Mike's recovery. Until it finally came out that Mike hadn't gotten the surgery at all. He got the placebo.

As drugs and people’s expectations change over time, does the nature of placebo response also change?

That is another great question. Current evidence suggests the answer is yes, it seems to be going up. It's not clear why. Perhaps it's some sort statistical quirk. It could also have to do with having a more informed, connected patient population. But my own feeling is that people just have more faith in certain types of drugs. Twenty-five years ago no one knew what Prozac was. Today it's a household name. And with that come heightened expectations.

Can the placebo response be explained by functional or neurochemical changes in the brain, and if it can, what engages those changes in the first place?

Certainly when it comes to pain, yes, we have a very good picture of what this looks like. Imagine burning your hand on the stove and putting it in an ice bath. Imagine that relief. It would start in your hand and travel up to your brain, right? The placebo effect seems to work backwards, starting in the prefrontal cortex as an idea ("I feel better") and then moving toward your body. Along the way, your brain reacts to this thought by releasing endogenous opioids that ensure that what you think is true actually is true. One could assume that a similar process is at work for things like nausea or anxiety, but it hasn't been quite so well mapped out yet.

What are examples of other forms of suggestibility that play a role in everyday life?

For me, the clearest one is taking a pill for a headache. I have this throbbing thing inside my skull and as soon as I take the pill and gulp down the water I take a deep breath and feel immediately better. But most of those drugs don't actually kick in for 20 minutes. And that's a key point. Placebo effects are not limited to sugar pills. They are also a key part of active treatments as well.

Another poorly understood phenomenon is how suggestibility affects our immune system. Why is it that in college I always get sick right after finals? How come I can will my self through certain colds when I have to and not at other times? This is actually a very exciting area of research. For my own part, I like to play with my expectations during cold season with some visualization exercises. I imagine my flu shot as a sort of suit of armor, deflecting all the germs near me (though this is not how vaccines work). And if I do feel a sniffle coming on, I eat a clove of raw garlic. A buddy of mine swears it reboots your whole immune system, and clearly some part of me believes him.

Why are people so suggestible? Does it have anything to do with our social nature?

Absolutely. There is some great work out of the University of Boulder that is teasing this apart a little. They have found that a conditioned placebo response (like what I feel when I take that headache pill) is fine, but what's even better is if I think lots of other people have had a response before me. Think of it like healing peer pressure. Early research suggests it's incredibly powerful.

What is the single most important message you want people to walk away with?

Suggestion is a powerful and amazing tool that you use every day of your life to feel better and be more effective. But it's not a panacea. Do not try to treat life-threatening illness with therapies that rely heavily on belief. And don't expect your children to have the same self-healing power you do.

About THE AUTHOR SPEAKS: Selected authors, in their own words, reveal the story behind the story. Authors are featured thanks to promotional placement by their publishing houses.

To purchase this book, visit: