Flow

Touch Typing May “Unclamp” the Brain and Promote a Flow State

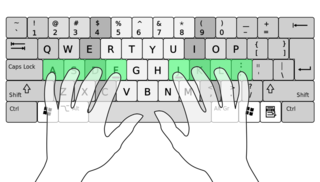

Typing without looking at the keyboard engages all four brain hemispheres.

Posted July 11, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Recent studies show that learning cursive and writing by hand engages sensorimotor brain regions and makes students better learners.

- When someone is new to a language, using a keyboard or digital device (not writing by hand) can slow down literacy learning.

- Once someone has mastered a language, learning to type without looking at the keyboard is a valuable sensory-motor skill.

"Unclamp, in a word, your intellectual and practical machinery, and let it run free; the service it will do you will be twice as good." —William James, "The Gospel of Relaxation" (1899)

Accumulating evidence suggests that learning cursive in elementary school and practicing the motor skills required for handwriting with a pen or pencil makes us better learners.

Writing by hand creates a "sensory-motor experience" that doesn't happen at a typewriter when someone is learning the letters of a new alphabet. Engaging one's sensorimotor brain regions when writing by hand improves literacy learning related to crystallized knowledge.

However, based on my life experience as a retired pro athlete turned full-time writer, I have a hunch that the motor skills required for automatized touch typing—using all 10 fingers and not two—creates another type of sensory-motor experience that may help fresh ideas flow from your fingertips without overthinking.

In this autobiographical blog post, I'm going to explain why I think typewriting (and not writing in longhand) has made me a more prolific writer and keeps my writer's block at bay.

Touch Typing Is a Unique Sensory-Motor Skill

When I learned touch typing in the early 1980s as a high school student, our classroom still had old-fashioned manual typewriters that made a cacophony of gratifying sounds. For example, every time you reached the end of a line, a loud dopamine-inducing bell would ding, and you'd manually move the carriage to a new starting line.

Before every "keyboarding" class, I'd get a rush of adrenaline knowing that the most skilled typists would be lined up at the front of the classroom like thoroughbreds in a starting coral and tested to see who was the fastest typist that day.

For me, touch typing felt like an athletic event; doing it really fast felt like running a 100-yard dash. Even though I had no idea where each individual letter was located on the keyboard, I could type upwards of 120 words per minute without looking at the keys.

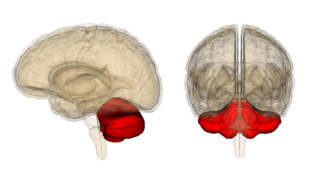

Because my neuroscientist father taught me that muscle memory is held in the cerebellum, I've always considered touch typing a cerebellar activity that relies on implicit, automatized motor skills.

Touch Typing May Promote Flow States and Fluid Thinking

Mastering my touch-typing skills as a teenager felt like learning a new muscle-memory sport. I loved practicing at the keyboard and getting "in the zone" by typing at lightning-fast speeds without looking at the keyboard. As a Star Wars fan, touch typing reminded me of Luke Skywalker learning to trust his gut and being able to hit a target with his eyes closed, like a Jedi Master.

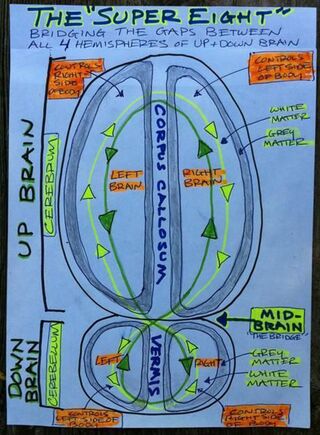

Interestingly, in most right-handed people, the right cerebellar hemisphere works in conjunction with the left cerebral hemisphere to facilitate the regulation of language functions. When writing by hand, left-handers would use more of their left cerebellar and right cerebral hemispheres. But touch typing engages all four hemispheres equally and makes skilled typists ambidextrous.

Recently, a systematic review (Starowicz-Filip et al., 2017) of the cerebellum's role in the regulation of language functions concluded: "Studies show that the cerebellum determines verbal fluency (both semantic and formal) expressive and receptive grammar processing, the ability to identify and correct language mistakes, and writing skills."

Teaching Cursive and Touch Typing May Optimize Whole-Brain Functions

In my opinion, it's a shame that more K-12 students don't learn touch typing in school. Just like learning cursive helps with the explicit knowledge associated with language literacy, the implicit knowledge of learning to type really fast without looking at the keys fine-tunes your muscle memory in a way that frees up your mind to express ideas using written words without overthinking.

Almost a decade ago, researchers at Vanderbilt University (Snyder et al., 2013) discovered that most skilled typists don't know where the letters are located on the standard keyboard. "The findings are consistent with theories of skilled performance and automaticity that associate implicit knowledge with skilled performance and explicit knowledge with novice performance," the authors explain.

For the type of writing that I do as a blogger, touch typing may allow me to create a state of "superfluidity" when I'm at the keyboard that feels frictionless and free-flowing. Of course, countless literary greats such as Joyce Carol Oates, Alice Walker, and Margaret Atwood are legendary for writing entire manuscripts in longhand. But for the "quick and dirty" thousand-word articles that I produce multiple times per week, if I had to write a rough draft by hand, it would slow me down and disrupt my flow.

Writing by hand also makes it more difficult for me to connect the dots between seemingly unrelated ideas. Although it's just a hunch, and I don't believe in the rigid delineations between left brain-right brain functions, something special happens when I'm touch typing really quickly that seems to engage my whole brain (all four hemispheres) in a way that makes me a more fluid writer.

Looking at My Blogging Process and Touch-Typing Skills Through a Metacognitive Lens

As a "meta" example: I came up with the idea for this blog post as I was lacing up my sneakers to go for a jog this morning and the sun was rising. While running, I did most of the heavy "cerebral" lifting in terms of coming up with the title, subtitle, thinking of the four studies I wanted to include, and making a list of key points.

In my mind's eye, I could picture the page's layout and created a loose narrative structure while I was jogging through the wilderness. The minute I got back to my car, I toweled off and opened my laptop, so I could transfer everything I'd thought of on my jog into a Google Doc. In less than 15 minutes, I'd touch typed over a thousand words and had the bulk of what you just read saved in a computer file.

Whenever I'm writing a storytelling narrative that blends evidence-based research with first-person observations, engaging the cerebellar parts of my brain seems to boost verbal fluency.

Take-Home Advice: Verbal fluency maps to opposing hemispheres in the cerebrum and cerebellum. Based on road-tested life experience, I hypothesize that when writers become skilled touch typists, they're often better equipped to optimize cerebro-cerebellar circuitry and language lateralization.

References

Robert W. Wiley and Brenda Rapp. "The Effects of Handwriting Experience on Literacy Learning." Psychological Science (First published: June 29, 2021) DOI: 10.1177/0956797621993111

Eva Ose Askvik, F. R. (Ruud) van der Weel and Audrey L. H. van der Meer. "The Importance of Cursive Handwriting Over Typewriting for Learning in the Classroom: A High-Density EEG Study of 12-Year-Old Children and Young Adults." Frontiers in Psychology (First published: July 28, 2020) DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01810

Anna Starowicz-Filip, Adrian Andrzej Chrobak, Marek Moskała, Roger M. Krzyżewski, Borys Kwinta, Stanisław Kwiatkowski, Olga Milczarek, Anna Rajtar-Zembaty, and Dorota Przewoźnik. "The Role of the Cerebellum in the Regulation of Language Functions." Psychiatria Polska (First published: August 29, 2017) DOI: 10.12740/PP/68547

Kristy M. Snyder, Yuki Ashitaka, Hiroyuki Shimada, Jana E. Ulrich & Gordon D. Logan. "What Skilled Typists Don’t Know About the QWERTY Keyboard." Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics (First published: October 03, 2013) DOI: 10.3758/s13414-013-0548-4