Flow

Psilocybin, Sublime Awe, and Flow Made “Oneness” My Religion

The genesis of my “oneness beliefs” boils down to three interconnected factors.

Posted April 20, 2019

A few days ago, I wrote a post, “Does ‘Flow’ Open Our Minds to Believing in ‘Oneness’?” which was inspired by a recent study (Edinger-Schons, 2019) published in the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. This follow-up post explores how “oneness became my religion” based on three key factors: Experiencing ego-dissolving awe in nature (this first happened when I was still a young church-going Mennonite in the 1970s), by achieving flow states and “superfluidity” through physicality, and a single life-changing experience on psilocybin during adolescence.

In my opinion, oneness is the antithesis of divisiveness. Unfortunately, discussions about “oneness” can get very abstruse and it's easy to slip into New-Age territory or "woo-woo" vernacular.

That said, my core foundation for believing in oneness is rooted more in neurobiology than spirituality. I strongly believe that the same feel-good molecules (e.g., endocannabinoids, adrenaline, endorphin, dopamine, etc.) that flood your body and brain when you’re in a “flow zone” flood my body and brain when I’m in a state of flow, too. Flow is a universal human experience.

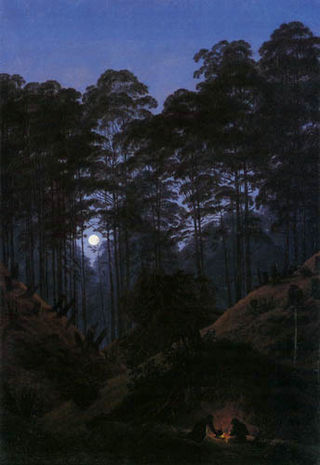

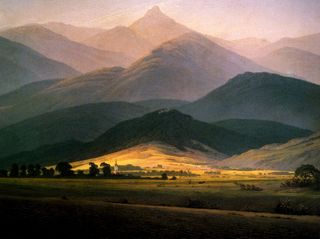

Additionally, the “small sense of self” (Paul Piff et al., 2015)—that we all experience when sublime awe makes us say “wow” and reminds us that there is something much bigger than us out there in the universe—is another core tenet of oneness beliefs. We all know the spine-tingling feeling of nature-inspired awe. It often happens when you look up at a full moon, see the Milky Way, or witness a breathtaking sunrise/sunset. All of these awe-inspired experiences have the ability to reinforce our sense of interconnectedness, human commonality, and oneness beliefs.

Lastly, I have a hunch that once the seeds of oneness have been planted by someone's early life experiences, that it only takes a single psychedelic experience (in a safe and expertly-monitored environment) to reaffirm that these universally accessible feelings of oneness are something that may seem ethereal but are actually real, and surround us every millisecond of the day.

My hope in sharing the following autobiographical experiences of how I stumbled on the power of oneness might serve as a hodgepodge road map for anyone reading this who is interested in nourishing his or her oneness beliefs.

As I sit here at my desk in the predawn hours, I'm touch-typing these ideas about oneness beliefs in a stream of consciousness fashion. That said, something just reminded me of a passage from C.G. Jung and Hermann Hesse—A Record of Two Friendships. In this book, the author, Miguel Serrano, recounts a story that during Jung's last known solacing dream before his death, he saw "a huge round block of stone sitting on a high plateau, and at the foot of the stone were the engraved words: 'And this shall be a sign to you of Wholeness and Oneness.'" (p. 104)

In another passage, Serrano explains Jung's possible relationship with this symbolic stone:

"Even as a child Jung had 'his stone,' on which he would sit for hours, fascinated by the puzzle of which was ‘I’—he, the little boy, or the stone. For years it was ‘strangely reassuring and calming' to sit on this stone, 'which was eternally the same for thousands of years while I am only a passing phenomenon.’ For Jung the stone ‘contained and at the same time was the bottomless mystery of being, the embodiment of spirit,’ and his kinship with it was ‘the divine nature in both, in the dead and the living matter."

For the next portion of this post, I’m going to share some of my own ego-dissolving experiences with oneness where “I” and the “other” became one over the years.

In my book, The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss (2007), I write about how archetypes and mythology laid a foundation for my oneness beliefs:

“Myths grabbed me somewhere deep down inside. They got into my spine. It was a metaphysical experience for me as a teenager because I realized that I and “the other” were one. This experience of complete connectedness is what I have coined superfluidity—the episodic feeling of existing without any friction or viscosity—a state of ecstatic bliss I will explore in this book.”

One ironic aspect of having strong oneness beliefs for me is that (in my case) feeling a sense of “oneness” has never been about belonging to a congregation or “tribe” of other people. Along this line, my affinity for self-determined solitude (SDS) is directly tied to the robustness of my oneness beliefs.

For me, being a “loner” and a “oneness seeker” are two sides of the same coin. This may seem like a paradox and requires discussing the potential dark side of obsessively craving the “flow zone” like a drug and using flow as a way to escape day-to-day life by tapping into oneness. Although the pros of flow wildly outnumber the cons, the "flow zone" has the potential to become a way of isolating yourself from others in unhealthy or self-destructive ways. (See, "The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure")

For example, in another passage from my first book I wrote:

“Many people, especially obligatory exercisers (like me), treat mental health problems with exercise. Be on the lookout for the warning signs of compulsive behavior, and if you think there’s a problem get help to sort it out. Please understand that a lot of what I accomplished as an athlete was a coping mechanism for me. In many ways, it was a substitute for not being able to really let people into my life. Instead of connecting intimately to other humans, I had an ongoing love affair with 'the other.'”

For the record: I wrote the above passage over a decade ago when I was still an exercise fanatic. Since retiring from ultra-endurance sports, I have a much healthier relationship with using flow/superfluidity to create oneness in "tonic level" doses and strive to nourish more wholehearted and intimately-connected relationships on a daily basis.

As mentioned, this post is purposely written in a free-association style. The ideas presented in this post are very much a work in progress. But that's OK; there's purposely no dogma being presented here. I’m a strong believer in the Van Morrison mantra from “In the Garden” where he sings, “No guru, no method, no teacher. Just you and I and nature.”

I don't have many answers or expert tips on exactly "how to" instill oneness beliefs. But I am optimistic that if more people start believing more strongly in oneness that we can break the snowballing divisiveness of “us” against “them” sentiment and rhetoric. (See, "Your Brain Can Learn to Empathize with Outside Groups")

As you can see, I’ve sprinkled some artwork from my all-time favorite Romantic-era painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) throughout this post and included a brief description of how using "theory of mind" to put myself in each landscape triggers "what-when-and-where memories" of oneness from places I’ve been. If you have visual cues that evoke a strong sense of oneness, I highly recommend placing them somewhere in your living space or pulling them up on a digital screen when your oneness beliefs need a reboot.

“The artist should paint not only what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him. If, however, he sees nothing within him, then he should also refrain from painting that which he sees before him. Close your bodily eye so that you may see your picture first with the spiritual eye. Then bring to the light of day that which you have seen in the darkness so that it may react upon others from the outside inwards.” –Caspar David Friedrich

In the final section of this post, I’ll try to keep the narrative grounded in a streamlined, chronological timeline.

Around the age of five, I have early memories of the seeds of awe and the “small self” being planted in my psyche. Because I was born and raised in Manhattan, some of my earliest memories are of walking like a sea of marching human ants on the sidewalk and being overwhelmed by jaw-dropping awe anytime I looked up at the skyscrapers that literally seemed to be scraping the crystal-clear blue sky above us. Also, finding bright-orange salamanders hiding under rocks at our summer house in the Berkshires planted early seeds of nature-inspired awe and nourished a strong sense of connectedness to other creatures in the wilderness when I was a youngster.

As a native New Yorker, Central Park has always served as a way to tap into the feeling of unspoken “oneness” with all the other joggers, walkers, skateboarders, cyclists, etc. in the park who are either wittingly or unwittingly seeking a state of flow. The solidarity I feel with these “flow-seeking” strangers from all different racial, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds never fails to reaffirm my core belief system of oneness. Although everyone in the park is a unique individual, it also feels like everyone working out in the park on any given day gets on the same wavelength.

I didn’t know about the term “flow” until around 1990, when I read Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's seminal book, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. However, with hindsight, I realize that I taught myself how to find the sweet spot between my level of skill and degree of challenge (to create what I now consider "flow") while hitting tennis balls against a backboard as a fifth grader. During this mid-1970s period, my family was living in rural Pennsylvania. I was lucky enough to have a tennis court on our property; this allowed me to spend a lot of time practicing my groundstrokes alone against a backboard.

As my tennis skill level increased, I intuitively figured out that if I moved farther away from the board and hit the ball harder and at more challenging angles, it helped me stay in the “flow channel" and improved my game. Coincidentally, The Inner Game of Tennis was a bestseller during this era and was one of my father's favorite books. Dad was also my tennis coach, and I suspect I had a loose understanding that getting into the "zone" as a tennis player was rooted in some Zen-like practices. But I didn’t have a name for these states of consciousness when I was ten. Interestingly, I still feel the exact same childhood sense of “oneness” I experienced back in the 1970s anytime I step onto a tennis court to rally with my 11-year-old daughter.

During this period of my childhood, I had a horse named Commander who was always a stone’s throw away because we had a big barn next to our limestone farmhouse. Commander was my soulmate. We formed a symbiotic relationship. Whenever it was warm enough, I’d ride him barefoot and without a saddle. Galloping full throttle through the cornfields on Commander during dramatic weather as a 10-year-old kid is the first time I can remember feeling really connected to something much bigger than me in nature. This sense of oneness and "transcendent ecstasy" became something that I continue to seek whenever I'm biking or trail-running.

At this impressionable period of child development, I was also attending Mennonite church every Sunday and strongly identified with Jesus’ messages about the "Golden Rule" and loving thy neighbor as thyself. Because the Mennonite church was at the top of a hill just a few hundred yards from my house, it felt like a home away from home. Notably, my Sunday school teacher, Cristina Neff, is probably the kindest, most generous human beings I’ve ever known. Although I don’t identify with any organized religion now, the lessons I learned by being part of that peace-loving community have stayed with me for life.

In the early 1980s, I attended a boarding school called Choate Rosemary Hall during the peak of the school's infamous Bright Lights, Big City era of rampant substance abuse. My classmates were notoriously busted at JFK for trying to smuggle in $300,000 of cocaine from Venezuela and made the front page of the New York Times.

Although this was a very dark period in my life, I did have a transcendent and mystical experience on psilocybin at boarding school that evoked and reaffirmed earlier feelings of oneness from my “days of innocence” in Lebanon, Pennsylvania. This very intense one-time mystical experience of realizing that everything in the universe was interconnected hardwired my “oneness beliefs” for life. Anyone who has felt the exuberant sense of finally comprehending the interconnectedness of eve-ry-thing while tripping on some type of psychedelic knows what I’m talking about.

That said, the second time I took 'shrooms, I ingested way too many grams of dried “magic mushrooms” and had such a terrifyingly bad trip that I haven't taken another dose of hallucinogenic drugs since the early ‘80s. Although I don’t condone recreational drug use, based on a growing body of evidence, trying psilocybin as a "oneness-evoking tool" is something you might want to consider trying at least once under very regulated and safe conditions. (See, "This Is Your Brain on Microdoses of Psilocybin")

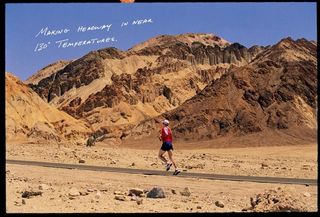

The bright side of having a petrifying bad trip—and developing a type of PTSD that made me way too spooked to ever take drugs again—is that I started using running as a way to go to a “special place” of connectedness and oneness without using drugs or alcohol when I was seventeen. Although most people hate running in hot and humid weather, I schedule my runs during the hottest time of day. I love sweating like crazy on blistering-hot summer days because once my body is covered in sweat, it feels like there’s no longer a barrier between "me," my skin, and the air around me. This is oneness.

Author's note: I wrote this post in one sitting and am well aware that the ideas presented herein are only half-baked and could probably be restructured in a much more linear and logical fashion. Nevertheless, in the tradition of Wabi-Sabi—which is basically the philosophy of purposely leaving art and creative expression in a "flawed" form without overthinking ways to make it "perfect"—I’m not going to be nit-picky or attempt to polish this post into perfection.

In closing, even though I'm not a poet, I want to share a poem I wrote decades ago, long before I used terms like “oneness beliefs." I wrote this poem in my head (without pen or paper) while I was jogging in Central Park after a psychoanalytic session at the William Alanson White Institute on the Upper West Side. Sometimes I recite this poem the same way someone might use a pair of rosary beads. When I was still competing in nerve-racking international competitions, I’d use this verse to help put me in a trance-like state so that I wouldn’t choke on race day. These days, the words remind me of specific ways to keep divisiveness at bay.

The Athlete’s Recognition by Christopher Bergland

Recognize that god is alive and well in every cell. Recognize that god is in us all.

Recognize this source of power—every hour, here. Recognize with strength and love there is no fear.

Recognize the light in every eye and soul. Recognize the sun lives in us all.

Recognize your thoughts and actions every day. Recognize the passion—always give your all.

Recognize One Blood, One Sun, One Hope, One Love. Recognize the collective conscience of humankind.

Recognize a trance like this. As you break a sweat—Drip. Drip. Drip.

References

Laura Marie Edinger-Schons. "Oneness Beliefs and Their Effect on Life Satisfaction." Psychology of Religion and Spirituality (First published online: April 11, 2019) DOI: 10.1037/rel0000259