Memory

30 Minutes of Aerobic Exercise Supercharges Semantic Memory

One half-hour of moderate exercise boosts neural processing of semantic memory.

Posted April 26, 2019

“Aerobic exercise triggers new cell growth in the hippocampus (memory hub). This growth of new neurons is called neurogenesis. Exercise promotes neurogenesis by increasing BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor). By increasing BDNF, aerobic exercise boosts your memory and makes you smarter. You can add neurogenesis to your list of reasons to exercise every day.” —Christopher Bergland (The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss, 2007)

When I published The Athlete’s Way in 2007, the idea that aerobic exercise could improve memory by triggering the production of BDNF—which is like Miracle-Gro for the brain and stimulates the birth of new neurons (neurogenesis) in the hippocampus—was a radically new concept.

Over the past decade, countless human and animal studies have identified a link between aerobic exercise, hippocampal neurogenesis, and improved memory. Yesterday, I reported on yet another study (McGreevy et al., 2019), which found that putting mice on a six-week cardio regimen stimulated neurogenesis in specific regions of the hippocampus and improved scores on memory tests.

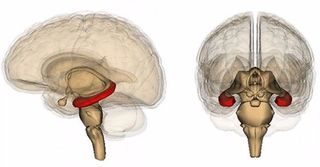

In addition to weekly exercise bulking up the hippocampus over time, there is a growing body of evidence that one bout of exercise boosts memory immediately after a workout. Last year, a study (Suwabe et al., 2018) by researchers in Japan reported that a single 10-minute bout of mild exercise such as yoga or tai chi enhanced memory by stimulating the dentate gyrus region of the human hippocampus.

As the authors explain, "A single 10-minute bout of very light-intensity exercise (30% VO2 max effort) results in rapid enhancement in pattern separation and an increase in functional connectivity between hippocampal DG/CA3 and cortical regions (i.e., parahippocampal, angular, and fusiform gyri). These results suggest that brief, very light exercise rapidly enhances hippocampal memory function."

Increasingly, the holy grail for neuroscientists studying the brain benefits of exercise is to dial in on the optimal “dose” (intensity × duration) of cardiovascular exercise or easy/light movement that is required to elicit various cognitive outcomes in the short- and long-term.

This week, a new study from the University of Maryland, “Semantic Memory Activation After Acute Exercise in Healthy Older Adults,” was published online ahead of print in the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. This research advances our understanding of the dose-response needed to activate brain circuits associated with semantic memory. Generally speaking, this refers to memories that relate to language, words, and names.

"While it has been shown that regular exercise can increase the volume of the hippocampus, our study provides new information that acute exercise has the ability to impact this important brain region," lead author, Carson Smith, who is an associate professor of kinesiology at the University of Maryland School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in a statement.

For this study, Smith and his UMB colleagues used fMRI neuroimaging to monitor the brain activity of study participants (ages, 55-85) and their ability to perform a memory task that involved identifying famous names on two separate days.

On the first day, a semantic "name recognition" memory test was conducted after a 30-minute session of moderate (70% of VO2 max effort) intensity cycling on a stationary bike. On the second day, participants came to the lab and sat in a waiting room prior to performing the “Famous and Non-Famous Name Discrimination Task” during fMRI brain scanning.

The researchers found that after 30 minutes of moderate-intensity cycling, participants correctly remembered more names. The fMRI also illuminated an uptick of activity in the hippocampus on both sides of the brain and increased activation of the middle frontal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus after one 30-minute aerobic session.

"Just like a muscle adapts to repeated use, single sessions of exercise may flex cognitive neural networks in ways that promote adaptations over time and lend to increased network integrity and function and allow more efficient access to memories," Smith said. In the paper’s conclusion, the authors write: “Coupled with our prior exercise training effects on semantic memory-related activation, these data suggest the acute increase in neural activation after exercise may provide a stimulus for adaptation over repeated exercise sessions.”

In addition to the long-term brain benefits of sticking with a regular exercise regimen throughout the week and across a lifespan, the latest research suggests that scheduling a 30-minute cardio workout at moderate intensity immediately before taking a written test or writing something that requires semantic memory might improve your performance.

As a writer, I know that my ability to access vocabulary words stored in my memory banks (from when I crammed for the SAT decades ago) as well as my overall ability to express ideas and thoughts via the written word, is always better after a 30+ minute jog.

That being said, if your schedule is tight or other daily logistics make 30 minutes of sustained moderate-intensity exercise impossible, remember that researchers in Japan found that 10 minutes of very light exercise (a slow walk or gentle yoga/tai chi) stimulates the dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus and boosts cognitive function in the short-term.

How to Gauge Exercise Intensity Using Color-Coded Exertion Levels and "Talk Tests"

You may be asking: How can I gauge my percentage of exercise intensity if I don’t know my VO2 max or have a heart rate monitor? Using a “talk test” is one of the easiest ways to gauge the intensity of your workout. To keep it gadget-free and straightforward, you can also visualize various exercise intensities as corresponding to three color-coded zones marked by yellow = light intensity, orange = moderate intensity, and red = vigorous intensity.

In the “easy/light” yellow zone you could carry on a lengthy in-depth conversation while strolling at a slow pace with a friend or doing some tai chi movements. When you're in the “moderate” orange zone during a brisk walk or slow jog, sentences automatically become shorter to avoid running "out of breath" because you're huffing-and-puffing a little bit. During intervals or HIIT training, when you’re in the “red zone” (upwards of 80% VO2 max effort) you are generally gasping for breath and can only speak two- or three-word sentences or give “yes and no” answers.

All of these exercise intensities are accompanied by an inner dialogue that can range from, "This is a breeze. I could walk and talk at this pace all day," to, "OMG! This is killing me! I can only sustain this level of exertion for a few more seconds."

When you're doing a high-intensity interval training (HIIT) workout with a series of intense bursts of exertion followed by an easy break—during the recovery phase between intervals, when your heart rate is hovering around 30% max—you might color code the intensity as "mellow yellow." On the flip side, during the bursts of 80% VO2 max (or higher) exertion during HIIT, you'd see fire-engine red, and the voices in your head are often dominated by an expletive-filled inner dialogue screaming, "Holy #$@&*! This workout is tough!"

Within these three "color-blocked" zones of aerobic intensity, there are innumerable shades of yellow, orange, and red. For example, if you're striving to achieve the new recommended guidelines (Piercy et al., 2018) of 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), you would spend about 22 minutes a day in a "mid-orange zone." But this orange color is on a spectrum that would fluctuate by taking on a more reddish hue (like the color in the upper-right corner of the abstract Pixabay image above) during brief periods of "vigorous" exertion while running up a hill or climbing some stairs.

The key to any well-structured "neuroprotective" workout regimen is to constantly mix-it-up by spending a little time in various zones of intensity every week and striving for about 30 minutes of MVPA aerobic exercise most days of the week, if possible.

DISCLAIMER: Please use common sense and consult with your primary care physician before beginning any new physical activity or kickstarting a vigorous exercise regimen—especially if you have not done any high-intensity physical activity recently.

References

Junyeon Won, Alfonso J. Alfini, Lauren R. Weiss, Corey S. Michelson, Daniel D. Callow, Sushant M. Ranadive, Rodolphe J. Gentili, and J. Carson Smith. "Semantic Memory Activation After Acute Exercise in Healthy Older Adults" Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society (First published online: April 25, 2019) DOI: 10.1017/S1355617719000171