Relationships

3 Things That Helped Me Learn to Love Solitude

Pop music + the joy of movement + being in awe of nature = amazing alone time.

Posted April 5, 2019

Yesterday, I wrote a post titled, “Motivations for Solitude Explain Why Loners Love Being Alone.” That piece was inspired by a recent study (Thomas & Azmitia, 2019) which explores a new 14-item questionnaire used to identify different motivations for seeking solitude. Their survey gauges the degree that wanting to be alone is motivated by "adaptive" solitude-seeking (e.g., alone time that helps people flourish) or "maladaptive" motivations for wanting to be alone that can exacerbate feelings of loneliness and perceived social isolation.

The prompt phrase for the 14-item survey is: “When I spend time alone, I do so because...” Then, there are 14 various scenarios (e.g., "I enjoy the quiet," "I value my privacy") that you rate on a continuum from "not at all important or relevant" to "extremely important and relevant.”

Of the 14 items on the short-form Motivation for Solitude Survey (MSS-SF), the six that resonate most strongly with me are “It sparks my creativity,” “Being alone helps me get in touch with my spirituality,” “It helps me stay in touch with my feelings,” "I feel energized when I spend time alone," “I can engage in activities that really interest me,” and “[Solitude] helps me gain insight into why I do the things I do.”

Yesterday’s post concluded with the promise of a follow-up that would give some autobiographical examples of how I learned to love “self-determined solitude” (SDS) when I was in the fifth grade. And how the fact that I unearthed random ways to love being alone when I was still a kid helped me cope with severe social rejection and “not self-determined solitude” (NSDS) in high school.

Before diving in, I want to give you a heads up that I’ve decided to write this post in a stream of consciousness, free-association, conversational style. In my early 20s, I spent many years in psychoanalysis at the William Alanson White Institute. As a thought experiment and writing exercise, I’m going to touch type this post as fast as I can without looking at the keys, while pretending I’m on a couch at the White Institute describing, “How I learned to love solitude and being alone when I was in the fifth grade" to my analyst. We'll see how it goes.

Last night, I kept tossing and turning in my sleep because this overarching question and task of tracing the genesis of learning to love solitude opened a floodgate of long-forgotten "what-when-where-and-who memories" from my past that started bubbling up from my subconscious like a geyser.

This morning, while I was waiting for the water to boil for coffee, I distilled the specific elements that helped me learn to love solitude and being alone to three key ingredients. Hopefully, my very basic method of facilitating “self-determined solitude” (SDS) will work for other people, too.

As you can see in the subtitle of this post, my simple equation for learning to love being a loner and making alone time feel amazing involves pop music + the joy of movement + being in awe of nature.

I accidentally stumbled on this triad of “SDS" enhancers as a 10-year-old in 1976. At the time, I had recently been transplanted from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan’s Upper East Side (where I was born in 1966 at New York Hospital) to the rural countryside of Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

My late father was a brain surgeon who trained at Cornell Medical School on York Avenue and we lived across the street in Phipps House. Sometime in the early 1970s, dad was offered the opportunity to launch a pioneering neurosurgery program in Hershey, PA. At the time, much of Milton S. Hershey’s chocolate factory fortune was being poured into building a new, state-of-the-art medical center. My father jumped on board.

Being uprooted from New York City and moving to the middle of nowhere was tough for me as a kid. Although I'm definitely not an extrovert, I was born with a relatively gregarious disposition. My earliest memories are of the carefree laughter and glee that I experienced while playing with the countless other kids my age who lived in our big “white elephant” apartment building.

Unfortunately, the old limestone farmhouse my parents bought in Lebanon, PA was surrounded by nothing but a cavernous barn with ominous Pennsylvania Dutch Hex signs, endless cornfields, and the silhouette of a Mennonite church you could see from our front porch at the top of a hill on the distant horizon.

The desolation and loneliness of this seemingly bucolic place were overwhelmingly intense for me as a native New Yorker. I felt like a fish out of water; it was as if my lifeline had been unplugged. I didn’t want to live in the middle of an isolated cornfield and missed having fun with my childhood friends back in the city. This first-time experience of forced solitude is Exhibit A of “NSDS” that I experienced before young adulthood.

Luckily, because dad had a good paying job, he quickly built a tennis court and bought each of his three kids our own horse. Mom and Dad signed us up for the Positive Youth Development and Mentoring Organization known as "4-H." Although I didn't really connect with the other kids in the program, I fell in love with horseback riding. My new soul-mate became my trusty steed named, "Commander."

Full disclosure: Because I’m writing this post from start to finish in a stream of consciousness mode, I just realized that bonding with animals was also vital to helping me learn to love solitude as a kid. Nevertheless, I’m not going to officially add “bonding with a horse or pet” to this list for pragmatic reasons. Owning animals is expensive and time-consuming, plus having a pet isn’t in the locus of a child’s control and isn’t feasible for many parents.

That said, I was very fortunate to have a horse that I could ride every day when I was in middle school. Horseback riding through the rural farmland of Pennsylvania in the mid-1970s was the conduit for me learning how to tap into a sense of spiritual connectedness and nature-inspired awe.

The euphoric feeling of connecting to some outside “Source” that was much bigger than me via nature started when I was about ten years old and triggered what I now call "transcendent ecstasy." Notably, fifth grade marked the rite-of-passage age when I was finally old enough for my parents to let me run wild on my horse through the cornfields and go wherever I wanted (within a five-mile radius) with Commander.

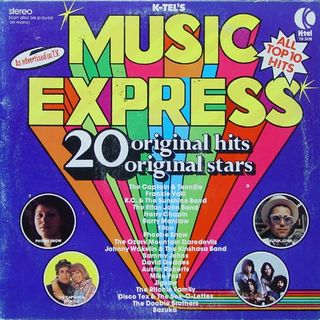

My love of Top-40 radio and listening to Casey Kasem religiously also began around this time. In 1975, I had started collecting records and would spend all of my free time at home blasting K-Tel records and vinyl 45’s that I bought at Woolworth’s. I listened to music on a pair of Radio Shack headphones with an extended cord that was long enough so that I could crank up the volume and “dance like no one was watching" alone in my bedroom.

Interestingly, the pop music of the era (e.g., “My Sweet Lord” by George Harrison) also helped me learn how to “get in touch with my spirituality.” As a fifth grader, I still attended Mennonite Sunday school. My all-time-favorite-teacher, Cristina Neff, loved the song “Morning Has Broken” by Cat Stevens. She played this religious-themed Top 40 hit every weekend at church. This song also became my anthem for getting up early and taking Commander for horseback rides at sunrise in the spring and summer.

To this day, anytime I hear “Morning Has Broken,” (like the other day in the checkout line at 7-Eleven) I’m transported back to the “conversion experience” of learning how to tap into a spine-tingling sense of bliss by connecting with nature. This pursuit of transcendent ecstasy through music, nature, and physical movement became my lifelong passion and was the genesis for what I now call “superfluidity.”

Around 1976, I discovered that my love of being alone benefited from physical movement by “dancing with myself” and practicing tennis against a backboard. As mentioned, dad built a tennis court on our property when we first moved to Pennsylvania. My father dreamed of coaching me to become the next Björn Borg. But dad's brain surgery responsibilities were extraordinarily demanding. We didn’t get to play tennis together as much as either of us would have liked, which created another source of NSDS loneliness for me.

That said, I practiced my groundstrokes alone against a backboard for hours-on-end every week. Once I got into the “zone,” hitting tennis balls against the backboard, I mastered the Zen-like art of losing myself completely in the “flow channel.” Mastering the ability to transition from “flow” to a frictionless state of “superfluidity” would come in handy later on in life when I became a professional ultramarathoner and ultra-endurance athlete. It’s impossible to feel lonely when you’re in the so-called “flow zone.”

As I’ve written about extensively over the years, I had a turbulent adolescence. The low point for me came when I was trapped at a very stodgy (and homophobic) boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, where I was ostracized for being gay. This forced solitude period is Exhibit B of "NSDS" that I experienced before turning 18. (For more see, "Having the Status Quo Turned Upside Down Can Free Your Mind.")

Luckily, the second time around, when I was forced into a situation where I felt completely abandoned and alone, I had the skillset and tools (e.g., pop music, physical movement, and experiencing a sense of awe in nature) to “flip the script” and embrace becoming a loner wholeheartedly.

In closing, all I can say is: "Thank god the Sony Walkman was invented in the early 1980s!" Having the ability to make mixtapes with all my favorite pop music and go for long jogs in the wilderness became my sanctuary and salvation during a very rough patch of NSDS as a teenager.

If you’re currently in a situation of not self-determined solitude, hopefully, making an effort to seek out some nature-inspired awe, listening to music, and experiencing the joy of movement will help you learn to love spending time alone, too.

References

Virginia Thomas & Margarita Azmitia. "Motivation Matters: Development and Validation of the Motivation for Solitude Scale – Short Form (MSS-SF)" Journal of Adolescence (First available online: November 23, 2018) DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.11.004