Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy

Psilocybin May "Reset" Brain Circuitry of Depressed Patients

Magic mushrooms may kick-start recovery from treatment-resistant depression.

Posted October 13, 2017

Psilocybin, which is the psychoactive and psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms, may have the ability to reset the functional connectivity of brain circuits known to play a key role in depression, according to a new study from Imperial College London. These findings were published online, October 13, in the journal Scientific Reports.

The authors note that although the initial results of using psilocybin to “kick-start” recovery from treatment-resistant depression are exciting, the study's sample size was small—and there was no control group or placebo cohort. Therefore, the ramifications of these preliminary findings on using magic mushrooms to treat depression should be interpreted with cautious prudence.

That said, there is growing evidence that psilocybin can trigger changes in brain mechanisms that are associated with remarkable improvements for a variety of psychiatric conditions including substance use disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and end-of-life anxiety. Now, for the first time, the new study from Imperial has identified a link between psilocybin and reduction of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) symptoms.

In a statement, lead author of the recent TRD psilocybin study, Robin Carhart-Harris, who is the director of Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, said:

"We have shown for the first time clear changes in brain activity in depressed people treated with psilocybin after failing to respond to conventional treatments. Several of our patients described feeling 'reset' after the treatment and often used computer analogies. For example, one said he felt like his brain had been 'defragged' like a computer hard drive, and another said he felt 'rebooted'. Psilocybin may be giving these individuals the temporary 'kick start' they need to break out of their depressive states and these imaging results do tentatively support a 'reset' analogy. Similar brain effects to these have been seen with electroconvulsive therapy."

For this study, Carhart-Harris and collaborators successfully enlisted 19 patients with treatment-resistant depression and gave them each two doses of psilocybin. The first dose was 10 mg. One week later, each patient was given the second dose of 25 mg of psilocybin.

Immediately following psilocybin treatments, all of the patients reported a decrease in depressive symptoms. This corresponded with anecdotal reports of an "after-glow" characterized by stress relief and improved mood.

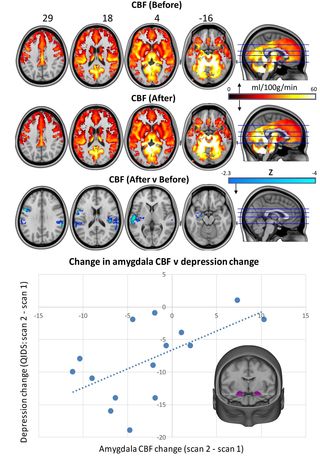

The researchers also used fMRI to monitor functional connectivity between brain regions and identified decreased blood flow to certain areas involved in emotional responses to fear and stress, including the amygdala. Conversely, they observed increased stability in another brain network associated with depressive symptoms.

Carhart-Harris summed up the main takeaway of these findings: "Through collecting these imaging data we have been able to provide a window into the after effects of psilocybin treatment in the brains of patients with chronic depression. Based on what we know from various brain imaging studies with psychedelics, as well as taking heed of what people say about their experiences, it may be that psychedelics do indeed 'reset' the brain networks associated with depression, effectively enabling them to be lifted from the depressed state."

Please note: The authors warn that people suffering from depression should not attempt to self-medicate with psilocybin. Even though these initial findings are encouraging, the research on psilocybin is still at a very early stage and more research is needed before making clinical recommendations. Also, the Imperial College London team takes extraordinary measures to ensure that nobody in their clinical studies ever has a "bad trip" by creating an ideal therapeutic context for having a psilocybin experience. The authors are well aware that it's easy for things to go awry outside of a controlled environment if the protocol required for psilocybin treatment is mismanaged or neglected.

What a Long, Strange Trip It's Been: My Personal Experience With Psilocybin

Anytime I read clinical research about psilocybin, it gives me flashbacks to my mind-altering experiences with magic mushrooms as a teenager. This is both a blessing and a curse.

The first time I tried psilocybin during high school, it was an amazing, eye-opening, ego-dissolving, and life-changing experience. I took a small dose of magic mushrooms and it cleared the cobwebs obscuring my perception of the world in a way that echoed what William Blake describes when he wrote, “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

My first psychedelic and "mystical" experience on magic mushrooms allowed me to realize (for the first time) the interconnectedness of everything and to feel absolutely zero friction, entropy, or viscosity between my existence and the universe around me. We were one entity. I describe this as a state of "superfluidity." It was profound.

Although my preliminary experience on magic mushrooms was life-altering in a very positive way, my second experience was psychologically terrifying and led to a minor case of PTSD. The second time I took magic mushrooms, I ingested too many milligrams of psilocybin and had a traumatic "bad trip." As I describe in The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss:

“I don’t know if you’ve ever had a bad trip, but it feels like all the tumblers in your brain are turning and re-configuring. Unlocking doors that should stay shut, closing windows that should stay open, all the while re-etching the blueprints of your psyche and the foundation of your soul. Fusing your synapses into new configurations and permanently rearranging the architecture of your mind.”

Needless to say, I can anecdotally corroborate the latest findings by Robin Carhart-Harris et al. regarding the power of psilocybin to “reset” someone’s brain circuitry by altering the functional connectivity between brain regions.

Because I've experienced the dark side of magic mushrooms, I'm always trepidatious when writing about the potential benefits of psilocybin or inadvertently condoning that anyone tries this drug. The recreational use of magic mushrooms really spooks me and I will probably never take psilocybin again. However, under controlled circumstances, the latest empirical evidence suggests that closely monitored doses of psilocybin in a supervised environment may have therapeutic benefits for patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression.

Below is a TEDx Lecture, "Psychedelics: Lifting the Veil" by Robin Carhart-Harris:

References

Carhart-Harris, Robin L., Leor Roseman, Mark Bolstridge, Lysia Demetriou, J Nienke Pannekoek, Matthew B Wall,

Mark Tanner, Mendel Kaelen, John McGonigle, Kevin Murphy, Robert Leech, H Valerie Curran, and David J Nutt. "Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms." Scientific Reports. (First published online: October 13, 2017) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-13282-7