Dreaming

No. 1 Reason Having Vivid Dreams Benefits Your Brain

Rapid eye movement sleep, theta rhythms, and dreams are key to memory formation.

Posted May 25, 2016 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

In the first century B.C., the Roman poet Lucretius was one of the first to observe rapid eye movement (REM) sleep when he wrote of watching one of his hunting dogs twitch as it lay sleeping by the fire. As Lucretius observed his dog's eyes dart back and forth beneath its closed eyelids, he noted, “the animal appeared to be chasing some type of phantom prey in its mind.” To the best of my knowledge, this is the first documented observation of REM sleep in a human or animal.

Surprisingly, modern scientists didn’t realize the significance of REM sleep until 1951. REM is the phase of nightly sleep when we do our most vivid dreaming and replay the events of the day through our nightly dreams.

Recently, a team of researchers has proven, for the first time, why REM (theta brain wave) sleep is believed to be a keystone of memory consolidation in all mammals, including humans. The researchers at Douglas Mental Health University Institute (McGill University) and the University of Bern used state-of-the-art optogenetics to confirm a causal link between rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and memory formation.

The May 2016 study, Causal Evidence for the Role of REM Sleep Theta Rhythm in Contextual Memory Consolidation, was published in the journal Science.

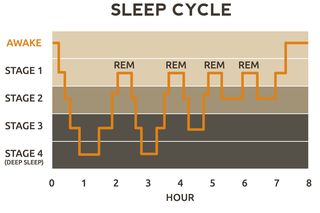

Cycles of REM sleep occur cyclically every 90 minutes and last for about 20 to 25 minutes. REM is the heaviest period of dreaming and learning during the sleep cycle. Within the rapid eye movement cycle, your eyes move in bursts occupying about one-third of REM sleep. Four of the five stages of sleep are non-REM. Adults spend about 25 percent of their nightly sleep cycles in REM sleep.

REM Sleep, Theta Rhythms, and Dreaming Consolidate Memories

Long before the advent of optogenetics, Rumi prophetically observed, “Though we seem to be sleeping, there is an inner wakefulness that directs the dreams. And that will eventually startle us back to the truth of who we are.”

For over a decade, sleep researchers have hypothesized that REM sleep is correlated with memory consolidation. But, as we know, correlation does not mean causation. What makes the new optogenetic study so groundbreaking is that prior to this revolutionary technique, establishing direct causality between neural activity during REM sleep and memory consolidation has been almost impossible because of the paradoxical nature of REM sleep.

In recent years, hundreds of various studies have tried unsuccessfully to isolate neural activity during REM sleep using traditional experimental methods. In this new study, the researchers used optogenetics, which allowed them to target a precise population of neurons and control neuronal activity using light.

In a statement, Sylvain Williams, co-author of this research and professor of psychiatry at McGill, said,

"We chose to target neurons that regulate the activity of the hippocampus, a structure that is critical for memory formation during wakefulness and is known as the 'GPS system' of the brain ... We already knew that newly acquired information is stored into different types of memories, spatial or emotional, before being consolidated or integrated. How the brain performs this process has remained unclear—until now. We were able to prove for the first time that REM sleep is indeed critical for normal spatial memory formation in mice.”

To test the long-term spatial memory of mice, the scientists trained mice to spot a new object placed in a controlled environment where two objects of similar shape and volume were standing. Mice tend to spend more time spontaneously exploring a novel object rather than a familiar one, which illustrates their use of learning and recall.

When these mice were in REM sleep, the researchers used light pulses to turn off their memory-associated neurons to determine if it would affect their memory consolidation. The next day, the same mice didn't succeed at the spatial memory task learned on the previous day. Compared to the control group, their memory seemed to be erased, or at least impaired.

"Silencing the same neurons for similar durations outside REM episodes had no effect on memory. This indicates that neuronal activity specifically during REM sleep is required for normal memory consolidation," the study's lead author Richard Boyce said in a statement.

We Learn When We Dream: Our Vivid Dreams Shape Our Memories

The process of hammering and forging our daily experiences into long-term memory through REM sleep is how we learn to master any sport, art, musical instrument, surgery, etc. through daily practice. REM sleep is a fundamental part of mastery. In The Athlete’s Way, I explore the research of Robert Stickgold, of the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School, who has dedicated his life to studying sleep as it relates to memory and learning.

As Stickgold explains, "Suppose you are trying to learn a passage in a Chopin etude, and you just can’t get it. You walk away and the next day (after a good night’s sleep), the first try, you’ve got it perfectly. We see this with musicians and with gymnasts. There’s something about learning motor activity patterns, complex movements: they seem to get better themselves.” On Page 313, I write,

“People who play the video game Tetris before bed dream of Tetris in their sleep and are better at it the next morning when they wake up. Poets who read or write iambic pentameter before they go to bed dream in iambic and write poems in their sleep.

Take advantage of the time before bed to prep your dreams by deciding how you want to launch yourself into your dreams. Conjure the things you would like to think about or work on in your sleep, and it will become a dreamscape reality.”

"I Can't Get No Satisfaction" Came to Keith Richards in a Dream

William Shakespeare wisely noted, “We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life, is rounded with a sleep.” The time we spend dreaming during REM is probably the most creative state-of-mind we experience within any given 24 hour period. For example, Keith Richards came up with the song "Satisfaction" in his sleep and recorded most of the song into a tape recorder by his bed.

The scientist Claude Bernard wrote extensive medical notes in a red book he kept by his bed and claimed to come up with most of his medical insights during his dreams. Not surprisingly, it turns out that the cerebrum and hippocampus play a role in cerebral long-term memory when you sleep. The cerebellum is also believed to play a key role in encoding procedural memories when we sleep.

There are thousands of anecdotes of creative greats having eureka moments when they dream. Each of us knows from first-hand experience how our imagination streams unrelated ideas together when we dream. Regular aerobic exercise, sleeping well, and vivid dreams go hand-in-hand. Regular exercise allows you to sleep deeper and dream better. The more regularly you exercise, the better you will sleep, the more you will dream during REM sleep, and the more of a creative powerhouse you will become.

Conclusions: REM Sleep Has Dramatic Brain Disease Implications

Because REM sleep and dreaming are a critical component of sleep for all mammals, including humans, poor sleep-quality is increasingly being associated with the onset of various brain disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease.

Statistically, REM sleep is significantly perturbed in Alzheimer's. The results from this study suggest that disruption of REM sleep may exacerbate memory impairments observed in AD, the researchers say. If you are one of the millions of Americans who suffer from sleep disorders, click here for some simple tips on improving your sleep quality.

To read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts,

- 12 Ways Eye Movements Give Away Your Secrets

- Sleep Loss Disrupts Emotional Balance Via the Amygdala

- Neuroscientists Decrypt the Mystery of Rapid Eye Movements

- The Whites of Your Eyes Convey Subconscious Truths

- Why Is Dancing So Good for Your Brain?

© 2016 Christopher Bergland. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.