Body Image

Out of Body Experiences: A Neuroscientific Explanation

Part 10: The TPJ's role in constructing our body schema can explain.

Posted August 23, 2019

I must now return to that critical question – what do we learn about OBEs by discovering a specific brain area that can induce them? Is the TPJ (the temporo-parietal junction) the mystical opening to worlds beyond? Is it the Astral Doorway or the spot God uses to transport us to heaven? Or is there something about the TPJ that explains OBEs as a natural result of brain function?

The answer is clear and very exciting. The TPJ is deeply involved in our sense of embodiment – the feeling that ‘I’ live inside my body and control it. Other brain areas close to the junction of the parietal and temporal lobes are ideally placed to bring together sensory information, emotions and memory to construct a body-schema and body-image (Decety & Lamm 2007). They connect areas of the limbic system, thalamus, and parts of the cortex, and especially the prefrontal cortex, to build up an impression of where our body is and what it is doing. They also contribute to perspective-taking, our ability to imagine being in someone else’s position and empathy.

These two terms, ‘body image’ and ‘body schema’, have often been used interchangeably, but more recently have been distinguished. The body image describes your appearance; how you think others see you, how your body looks, and how attractive you feel. The body schema refers to the continuously updated model of your body with its posture, actions, and position in space. This is essential to your behaviour, as it is to any animal that moves around, whether that’s a frog, a dog, or an eagle. It needs to be detailed, accurate and rapidly updated.

You may, right now, be sitting in bed or in a chair and looking at a book or screen. Take a moment to shut your eyes and feel your whole body. You will probably have a clear image of the position of your arms and legs, the angle of your neck and head, and the sensation of pressure on your chair or your elbows on the table. This is your body schema. It works automatically all the time without you bothering about it, but you can deliberately feel it if you want to. You can also use it flexibly when you imagine jumping up, running across the room or even flying like a bird.

This body schema is combined, at the TPJ, not only with hearing, sight, taste, and smell, but with the vestibular system that keeps our balance, and with thoughts, imagination and memories that are sustained in other parts of the temporal and parietal lobes, and with intentions and control functions handled in the frontal lobes to create a rich sense of self that goes beyond just the body. Bringing all this together is what provides the sense that you are an integral human being, in this particular position, carrying out these actions, having these intentions and thinking these thoughts right now.

Does this help us understand the OBE? Yes, I think it makes all the difference. For the first time, we can base this wonderful experience firmly in brain function. If the TPJ is disturbed, some of the functions needed to create an accurate body schema fail. This is why Blanke and his colleagues refer to OBEs as depending on “disturbed self-processing at the TPJ” (Blanke and Arzy 2005), “failure by the brain to integrate complex somatosensory and vestibular information” (Blanke et al 2002 p 269). Although their way of describing OBEs sounds rather dismissive, what they mean is that when parts of the TPJ are disturbed, an effective body schema cannot be maintained, and the result is an OBE.

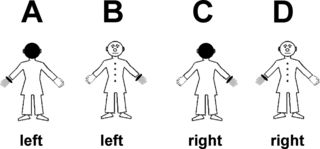

If they are right, the TPJ should be activated when people imagine being out of their body, and this has been confirmed using a method called evoked potential mapping. Volunteers were given the ‘Own Body Transformation Task’, illustrated here. You can try it yourself by imagining rotating your own body so as to answer the question – is the grey hand the figure’s left or right hand? Researchers found that the TPJ was selectively activated while people were doing this task (Blanke et al, 2005 p 550).

There are some problems with the methods used for this experiment, explained in more detail in my book (Blackmore 2017), but the general finding has since been confirmed in other ways. For example, if TPJ activity is necessary for imagined body transformations then disrupting it should make the task harder, and this has been shown by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, which disrupts normal functioning. As expected, TMS applied to the TPJ interfered with people’s ability to do the transformation task and did not affect their imagining other objects being transformed.

Other relevant findings are that people who have OBEs experience more disruptions of own-body processing in general and may be worse at the transformation task (Braithwaite et al, 2011). Yet there is a flip side to all this. We know that the TPJ is also involved in taking another person’s perspective and Kessler and Braithwaite (in print) suggest that ‘genuine OBEs should not be regarded as a flaw in the system of certain individuals but as “the other side of the coin” of full-blown perspective taking’. There is also the fact that some people can deliberately induce an OBE, which implies they have a real skill rather than a failure. There is clearly a lot more to learn and many new questions opened up by this research, but the most important step has been taken. We know which part of the brain is involved in OBEs and the reason is that it maintains, or alternatively plays with, our body schema.

References

Blackmore, S. 2017 Seeing Myself: The new science of out-of-body experiences, London, Robinson

Blanke, O., & Arzy, S. 2005. The out-of-body experience: disturbed self-processing at the temporo-parietal junction. The Neuroscientist, 11, 16-24.

Blanke, O., Mohr, C., Michel, C. M., Pascual-Leone, A., Brugger, P., Seeck, M., ... & Thut, G. 2005. Linking out-of-body experience and self processing to mental own-body imagery at the temporoparietal junction. The Journal of Neuroscience, 25:3, 550-557.

Blanke, O., Ortigue, S., Landis, T. and Seeck, M. 2002 Stimulating illusory own-body perceptions. Nature, 419:269-70

Braithwaite, J. J., Samson, D., Apperly, I., Broglia, E., & Hulleman, J. 2011. Cognitive correlates of the spontaneous out-of-body experience (OBE) in the psychologically normal population: evidence for an increased role of temporal-lobe instability, body-distortion processing, and impairments in own-body transformations. Cortex, 47(7), 839-853.

Decety, J., & Lamm, C. 2007. The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: how low-level computational processes contribute to meta-cognition. The Neuroscientist, 580-593

Kessler, K., & Braithwaite, J. J. (2016). Deliberate and spontaneous sensations of disembodiment: capacity or flaw?. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 21(5), 412-428.