Sex

Do Sex Workers Have More Mental Health Problems?

Sex workers' mental health depends heavily on what kind of sex work they do.

Posted October 30, 2014 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

I don’t typically write about sex work for this blog, but sex for money, whether you are the one paying or the one being paid, much of the time is casual sex—sex with someone you are not emotionally attached to or romantically committed to—only with the added component of money exchange. At a time when sex work and its legal status are being hotly debated across several Western nations (including our northern neighbor), it’s worth taking a look at some of the scant research available on this topic. Particularly, the question of mental health.

A frequent assumption is that sex workers have more mental health problems than the general population. Some believe that it is their mental health problems that got them into sex work in the first place, while others contend it’s the nature of the job—from social stigma to legal and health risks, to exposure to violence and abuse—that causes their mental health to suffer. To my knowledge, no longitudinal study capable of addressing the causality issue has been conducted, but there is another, related issue that often goes unaddressed—the type of sex work.

Not all sex work is created equal—hustling on the street to feed a drug addiction and having sex in a car or a shady motel by the hour carries very different levels of risk and stigma than does advertising online and meeting your clients at a private studio or high-end hotel. Being forced or pressured into sex work by a dishonest employer, an abusive partner, or dire financial circumstances is very different from actively choosing sex work because you enjoy it more and/or find it to offer better perks (e.g., more money, flexible hours) than the other job options you have. These differences are bound to leave different marks on your mental health.

Unfortunately, no published U.S.-based research looks at different mental health profiles across different types of sex workers. But this 2010 Swiss study offers a rare glimpse. In Switzerland, sex work is not illegal, and in 2005 in Zurich, there were about 4,000 legally registered female sex workers. For this study, researchers recruited 193 of them, contacted through a variety of locations (outdoors, studios, bars, cabarets, parlors, brothels, and escort services), and interviewed them at length about their mental health and experiences with sex work. The sample was 53% Swiss, 27% other European, and 19% non-European, and ranged in age from 18 to 63 (mean = 32), in age at first sex work from 12 to 52 (mean = 24), in days working per week from 1 to 7 (mean = 4), and in customers per week from 1 to 60 (mean = 14).

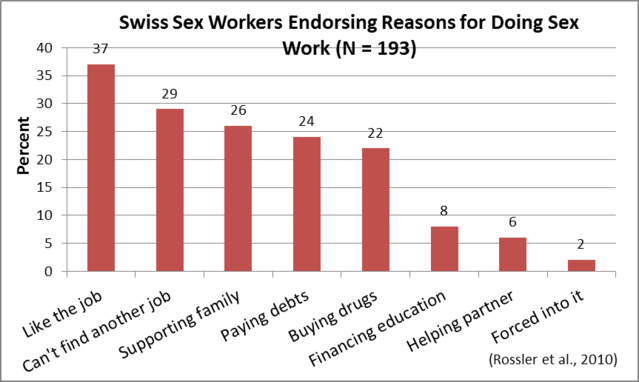

There are many fascinating tidbits of data in this study, like the one that the women’s weekly average income of €1,200 (range from €90 to €6,300) surpassed significantly the average income of Swiss residents at the time, which was only €900. However, sex workers also varied widely in the percent of income that was at their own disposal, from 0 to 100 percent (mean = 77 percent), with only a third having access to the full amount they earned. Then there was the finding that 45 percent of sex workers reported no desire to quit and that the single most common reason for doing sex work was “liking the job,” endorsed by 37 percent, while the least common was “being forced,” endorsed by 1.6 percent (for the rest of the reasons, see the graph below.)

But for the rest of this piece, let me focus on the mental health issue. Overall mental health problems were fairly high, with 50 percent of sex workers reporting at least one psychiatric disorder over the last 12 months; by comparison, this is true of 22 percent of the general population of adult U.S. women. The most prevalent disorders were mood (30%), anxiety (34%), post-traumatic stress syndrome (13%); none were diagnosed with schizophrenia or alcohol dependency.

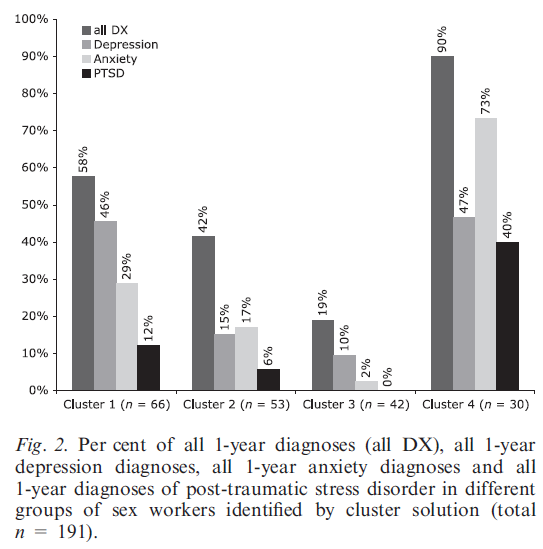

But were some sex workers at a higher mental health risk than others? The researchers suspected that this might be related to the women’s country of origin, where they worked (street/car, hotel, studio, brothel), how much social support they got, and how much violence within and outside the sex work context they experienced. When they plugged these variables into a statistical procedure called "cluster analysis," sex workers clustered into four distinct groups. And, when they further looked at the mental health profiles of the women in the different clusters, they saw marked differences.

On one end of the spectrum were the women in Cluster 4 (n = 30). These were virtually all non-European, working out of studios or brothels, and experiencing low levels of social support, and high levels of pressure, violence, and rape as part of their work (though very little of it outside of the work context). Their mental health was in poor shape: 90 percent had at least one psychiatric issue.

On the other end of the spectrum were the women in Cluster 3 (n = 42). They were of mixed European origin, worked mostly in studios or as escorts, experienced high levels of social support, and relatively little violence, pressure, or rape outside of work, and little to none within sex work. Their mental health was quite admirable. They were very similar to the general U.S. female population in the prevalence of depression or any psychiatric diagnosis, and were actually in much better shape when it came to anxiety or PTSD: 2 percent and 0 percent reported past-year anxiety and PTSD, respectively, compared to 23 percent and 4 percent of US women in general.

The two other groups were somewhere in between these extremes on their mental health. The women in Cluster 1 (n = 66) encompassed mostly Swiss fulltime sex workers working outdoors (in cars and on the street) or in hotels, who experienced most violence and rape across both work and non-contexts, and had very little social support. Over half of them (58 percent) had mental health problems. Finally, the women in Cluster 2 (n = 53) were of unspecific cultural background, worked primarily in brothels, salons, or cabarets, and, similar to Cluster 3 women, experienced some violence outside of sex work, but not much from sex work itself. Their mental health was somewhat better than of Cluster 1, but still 42 percent reported at least one psychiatric diagnosis.

Like all studies, this one has its limitations. It’s correlational, and therefore cannot establish what came first, sex work or mental health problems. It also likely underrepresents women who were entirely forced into sex work or who were working illegally (whose mental health is probably on par with, if not worse than, that of Cluster 4). Nonetheless, this study demonstrates the incredible diversity that characterizes the world of sex work and its mental health correlates. Ignoring this diversity and treating all sex workers as one homogeneous group when forming attitudes or making policy decisions is bound to lead us to wrong conclusions, even when most well-intentioned.

Have a casual sex story to share with the world? Or want to read other people's hookup experiences? That's what The Casual Sex Project and @CasualSexProj are for.

References

Rossler W, Koch U, Lauber C, Hass A-K, Altwegg M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Landolt K. (2010). The mental health of female sex workers. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122, 143–152. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01533.x [free pdf]