Bias

Is a Zero-Risk Bias Impairing Your Crisis Response?

Cognitive biases can explain bizarre behaviours of panic buying and hoarding.

Posted March 19, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Three days ago, a blind grocery shopper in Australia had a stash of toilet paper stolen from her supermarket trolley. Two days ago, a store in Scotland reported the theft of toilet rolls from their customer bathrooms. Yesterday, someone broke into a parked car in Oregon, USA, and nicked the two packs of toilet paper stowed in the back.

Panic buying, stealing and hoarding of household items like toilet roll has been one of the bizarre reactions to the global outbreak of COVID-19. And while it's certainly logical to make provisions for sustained periods of self-isolation, it is hardly conceivable that a year’s supply of toilet paper is going to protect people against a fast-spreading virus epidemic.

So why do people stock up on toilet paper when they should be prioritising evidence-based advice for infection prevention? Unless someone has discovered a way of using toilet roll to build airtight protective walls, thorough hand-washing is definitely going be more effective in keeping you safe! Extreme hoarding may appear laughable, but the behaviour points to deeply engrained psychological biases that affect the way we respond to risks.

Risk aversion and uncertainty aversion are well-known human character traits, which undoubtedly evolved to prevent reckless actions in favour of safer behaviours. However, while it might be fully rational to avoid dark streets in shady parts of town, some aspects of risk avoidance (like stealing toilet paper from a blind person) are a lot harder to justify.

Zero-risk bias

One reason for the absurd incidents of toilet paper theft could be an underlying psychological phenomenon typically referred to as zero-risk bias. This bias describes the irrationally strong preference for situations with absolute certainty. Nobel-prize winning researchers Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, for example, found that people preferred a risk reduction from 5% to 0% over a risk reduction from 55% to 50%, even though the total risk reduction in the two cases was identical.

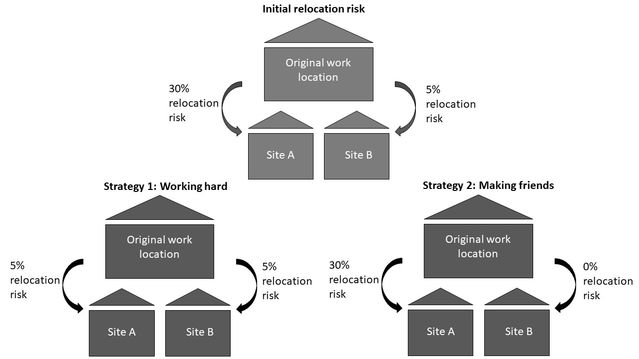

Follow-up research provided further evidence confirming the irrational bias. A recent study conducted in Germany investigated strategies for risk management in a hypothetical work dilemma. Participants were asked to imagine that their current workplace was undergoing a process of restructuring, meaning that many employees would have to move to one of two less desirable sites outside the city (let’s call them Site A and Site B). Participants also received the following information about their exact relocation risks:

With a 65% probability you get to stay in their current location.

With a 30% probability you will have to move to Site A.

With a 5% probability you will have to move to Site B.

To reduce their risk of relocation, they were subsequently presented with the choice of two different strategies.

If you choose Strategy 1 (e.g. working very hard to impress the boss), you will reduce your risk of being sent to Site A by 25%. Consequently, your new risk of relocation to Site A will be 5%.

If you choose Strategy 2 (e.g. befriending the building manager of the new sites), you will reduce your risk of being sent to Site B by 5%. Consequently, your new risk of relocation to Site B will be 0.

For an overview of the two risk reduction strategies, take a look at the figure below.

From a rational point of view, the choice between the two strategies is a no-brainer. Strategy 1 should be the clear winner, because it reduces the overall risk of relocation by a greater amount (25%) compared to Strategy 2 (5%). Nevertheless, the researchers found that almost half of the participants chose Strategy 2. Their choice suggested a preference for eliminating the relocation risk to Site B completely—even if this meant being at a higher overall risk of relocation.

The zero-risk bias may appear baffling at first, but it can be explained when considering the cognitive processes that underlie it. The existence of two or more different risks (such as moving to Site A and moving to Site B) presents decision makers with a tricky cognitive challenge. To simplify the situation and reduce the cognitive strain, eliminating one of the risks can be an appealing solution.

Zero-risk bias and COVID-19

The current epidemic presents almost unprecedented levels of risk and uncertainty. People are grappling with the fear of contracting a potentially life-threatening illness, while balancing worries about job security and sustenance during periods of self-isolation. The need to simplify this difficult situation, therefore, comes as no surprise.

As shown above, one way of tackling complex threats is to reduce the number of risk sources and eliminate one threat in its entirety. In this context, the hoarding of toilet paper can be interpreted as strategic action to control at least one aspect of the multifaceted threat. While it is impossible to contain a deadly disease, an ample supply of toilet paper leaves people reassured that their regular visits to the bathroom will be unaffected. At least one less thing to worry about!

The zero-risk bias can provide a compelling explanation for seemingly bizarre actions such as toilet paper theft. This certainly does not mean that attacking others in the fight over household items is acceptable behaviour. In crisis situations, it is essential to keep a clear head and control emotional reactions or bias-driven behaviours.

While some supermarkets are introducing protected shopping hours for elderly and vulnerable customers, everybody can make an effort to reduce irrational behaviour. Finding some peace of mind in the midst of chaos and uncertainty can go a long way. This fantastic collection of yoga classes by YouTube sensation Adriene Mishler aims to diminish feelings of stress and anxiety during difficult times. I suggest you give it a go next time you feel the urge to splash out on yet another bumper pack of toilet roll!