Coronavirus Disease 2019

Anticipating the Wave of Long-Haulers After the Pandemic

A contested illness on the horizon: how to think about the coming surge.

Posted February 2, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

One of my friends and colleagues had COVID last March. Her illness was prolonged and nearly landed her in the hospital. She couldn’t get out of bed for days and each breath, she said, was like breathing fire. A former competitive athlete, she couldn’t move around the house without her oxygen levels dipping into the low 90s. Even worse, her once keen intellect deteriorated to the point where she was only capable of brief coherent conversations once, maybe at most, twice a day. It was very scary but not at all unique.

Today, she’s one of the lucky ones. She made it through to the other side, albeit not without a cost. For weeks she continued to cough and feel breathless. Her hands and feet took on a purple hue due to poor circulation. When I pricked her finger in April for a spot of blood for a point-of-care antibody test, she had to vigorously shake and massage her hand before even a drop would emerge. “My hands,” she remarked, “are always so cold. They never were before.”

Now, nearly a year later, her hands are still cold. She’s living with intermittent ringing in the ears. Sometimes she can climb stairs without difficulty, but other times she feels woozy. Her heart races sporadically and she’s almost always easily winded. She has Long-Haul COVID.

You’ve probably heard about Long-Haul symptoms like this. The list of afflictions is as varied and mysterious as COVID itself can be and estimated to be present in roughly one in ten COVID survivors. And while there are some people, like my friend, with symptoms that are mostly measurable and observable, there are many others who have less tangible manifestations such as fatigue, insomnia, and “brain fog.” I’m no stranger to brain fog, myself — especially the week after we change the clocks for spring forward — but at least I always know it will dissipate. With Long-Haul COVID, it seems, brain fog is common, aggravating and persistent.

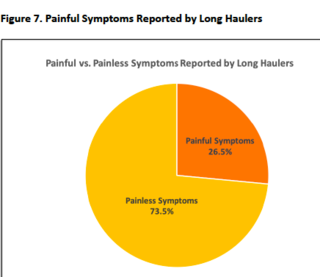

A survey published last year by a grassroots COVID-19 group called “Survivor Corps” found that “fatigue” was the most common symptom experienced by a group of more than 1,500 Long-Haulers. Also included among the top 10 symptoms were: “difficulty concentrating or focusing,” “difficulty sleeping,” “anxiety,” and “memory problems.” That sounds like a perfect storm of brain fog.

I spoke with Dr. Avi Nath, the Clinical Director of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke at the NIH and the author of a September 2020 commentary on “brain fog” in the journal Neurology. We discussed potential causes of brain fog and other post-COVID symptoms including persistent inflammation, the unmasking of underlying comorbidities, persistent infection or viral replication, and autonomic dysregulation.

Dr. Nath’s tone was measured without being evasive. “Yes,” he said, “I think it is true that COVID Long-Haul may follow the pattern of some other viral illnesses. Most people will get better but a small percentage will not and some of them will develop a chronic fatigue syndrome picture.”

Chronic fatigue syndrome, along with Chronic Lyme and Morgellons’s Disease are among a growing list of contested illnesses. If there is one thing to know about contested illnesses it is that, like contested elections, they raise hackles. Which is why, right now, we should be asking this question:

With COVID Long Haul, are we witnessing the early days of the largest and most significant contested illness surge in modern history?

In his long and distinguished career, Avi Nath has seen this play out before, but identifying the link between acute viral infection and chronic symptoms has been a mostly elusive endeavor. “Unfortunately,” said Dr. Nath, “there will be some Long Haul patients that just don’t get better and go from doctor to doctor looking for answers. And, there will be uncertainty if they have neuroinflammation or psychiatric pathology.”

In other words, Long-Haul COVID seems likely to take on the mantle of a contested illness. As we forecast the astounding total sum of COVID-19 infections globally, this is troubling and problematic in myriad ways. The potential for conflict between doctors, patients and patient-advocacy groups is staggering, especially as one considers other dynamics, such as unscrupulous profiteers looking to make a profit off of COVID-19 survivors, a potential flood of disability claims, and an evolving landscape of medical publishing that could sow confusion as to the evidence-based consensus on the how, what and why of Long-Haul COVID.

To better understand the genesis of contested illnesses and how we can prepare for what could be a new one, I video conferenced with Dr. H. Gilbert Welch in his home in Vermont. Welch is affiliated with the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and has written extensively about the concepts underpinning contested illnesses and a corresponding crisis of over-diagnosis and over-testing. We discussed some strategies for a constructive rather than destructive Long-Haul.

1. First, noted Welch, we should “inoculate the public.” The goal is to present the concept of Long-Haul COVID without entrenching it in opinion (for instance that it is either all real or all B.S.) and in a manner that recognizes the gray zones and need for much more study.

2. Second, COVID Long-Haul patients and advocacy groups should expect a level of scrutiny and, hopefully, see this as healthy. Ideally, sufferers would want their practitioners to consider other causes for symptoms such as “brain fog.” Doing so is not “medical gaslighting,” as some have suggested, but rather part of the sound diagnostic process known as “differential diagnosis” that recognizes the potential overlap between COVID-19 and other neuropsychiatric conditions.

3. Third, we should concentrate treatment and diagnostic efforts on those with symptoms and avoid screening or scaring people who feel well. The last thing we want to do is create disease where only fear exists. As with cancer screening in low-risk populations, the more the screen, the more we may find, but the less confident we will be that what we find is real.

4. Finally, Welch suggested, it is worth recognizing that patient advocacy can be a two-tailed dynamic. Certainly, patient advocacy can help raise awareness and provide support (psychological and otherwise) to people who are suffering. But, sadly, it can also encourage and empower charlatans looking to profit off of distress. This is the dynamic that has caused some in the “Chronic Lyme” community to search far and wide for “Lyme literate” doctors, who tend to charge large out-of-pocket costs for questionable service.

It may seem too soon to consider this, but it’s not. Indeed, post-COVID pathology is shaping up to be just as widespread and uncharted as COVID itself. Soon, I predict, physicians, like myself, who work in emergency departments and our colleagues in primary care will be on the front lines of Long-Haul frustration. We will see the patients with brain fog, and intermittent dizziness and cognitive delay. And we’ll have to tell many of them that we don’t have the answers or treatments they are looking for. When they leave us without solutions, where will they go? It is time start talking honestly about how to approach this next wave and to conduct the research necessary to provide COVID Long-Haulers with real help.

My friend has adapted to her new limitations and has returned to a very high level of professional function. While she does report some "brain fog," she isn’t sure whether that is residual from COVID or the byproduct of the stress of navigating COVID times where everyday life is overwhelmed with a series of no-win decisions that pit fear and risk versus normalcy and mental health. To the extent possible, she has successfully adjusted to Long Haul COVID. She is a lucky one.

References

1. BMJ 2020;370:m3026. https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3026

2. Nath, A. (2020). Long-haul COVID. https://n.neurology.org/content/95/13/559