Myers-Briggs

Detecting Bull**it

If you're interested in psychology, don't fall for psychology-adjacent woo.

Posted October 25, 2021 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Many people who are drawn to psychology are also drawn to psychological-sounding woo.

- Astrology, homeopathy, the Myers-Briggs, & the ideas in The Secret all lack evidentiary support -- and can be harmful.

- If you're interested in psychology, you should know why these ideas are bunk.

‘“You needn’t go on making remarks like that,” Humpty Dumpty said: “they’re not sensible, and they put me out.”’

– Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

Psychology is the science of mind and behavior. It has nothing to do with astrology, The Secret, or other New Age twaddle. But many smart people who are drawn to psychology are sometimes also drawn to psychological-sounding woo. Should we be concerned?

So What?

Maybe it doesn’t matter. Some people think these beliefs are fringe and mostly harmless – and besides, most people don’t believe this stuff anyway. But polls suggest the opposite: most of us aren’t completely tethered to reality. 73% of Americans have at least one paranormal belief. A variety of pseudosciences enjoy wide appeal in public society. Woo literally kills people. Carl Sagan’s famous foreboding? Gone and boded already, damn it.

The point of this post is to offer readers some information about five attractive-but-empty ideas and have a bit of fun in the process.

1. Astrology

Penny: “I’m a Sagittarius, which probably tells you way more than you need to know.”

Sheldon: “Yes, it tells us that you participate in the mass cultural delusion that the sun’s apparent position relative to arbitrarily defined constellations at the time of your birth somehow affects your personality.”

– The Big Bang Theory

Astrology is the belief that the position of celestial bodies at the time of your birth influences your personality and life course.

Here’s why this is nonsense.

First, empirical tests of astrological predictions show that they don’t work. A meta-analysis of more than 40 controlled studies shows that expert astrologers perform no better than chance, even at predicting basic personality traits such as extraversion. Double-blind tests show that astrological predictions are not supported by the evidence. Second, there is no known mechanism by which the planets could influence your personality. Third, in case you’re thinking it has to do with gravity, it doesn’t – the gravitational pull of the doctor in the room at the time of your birth was stronger than the gravitational pull exerted on you by the planets in our solar system at that same moment. Fourth, for astrology to be correct, it would have to negate pretty much everything we know about physics and psychology. Fifth and finally, there are good reasons to think that belief in astrology is driven by a combination of cognitive biases (such as myside bias) and ambiguous writing (such as Barnum statements). There’s no bona fide connection between the planets and our personality – there’s just no special Szechuan sauce there.

On a more serious note: it’s helpful to keep in mind that as humans, we have a tendency to see patterns even where there aren’t any. This can be understood through mathematical insights from Ramsey Theory combined with evidence that our minds are promiscuous pattern detectors.

By the way, these cognitive biases are a human universal, and we all struggle with them. Nobody is immune! So don’t feel bad if you, like the rest of us, sometimes fall prey to these human foibles. The hope is that learning how these cognitive biases lead us astray will help us become more vigilant when we hear claims about how the world works.

For a dystopian take on the dangers of taking astrology too seriously, check out Season 2 Episode 5 of science fiction series The Orville.

2. The Myers-Briggs Personality Test

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is the most popular personality test in the world – but alas, it’s mostly bullshit. It offers inconsistent results, doesn’t predict life outcomes, ignores key personality variables, and is based on empirically unsubstantiated ideas. The Myers-Briggs Company contends that "the MBTI assessment is designed to be descriptive, not predictive," but it is widely used to predict workplace behavior.. Check out this essay for a deeper look at the Myers-Briggs.

As the famous quip goes, it’s good to have an open mind, but if you open your mind too much, your brain might fall out [1].

3. Homeopathy

Homeopathy is a form of alternative medicine based on the idea that “like cures like” and that diluting substances increases their potency. (Yep, this one’s pungent).

A good way to know that this is bullshit is 1) controlled studies show that homeopathy fails to outperform placebo, 2) it contradicts vast swaths of physics, chemistry, biology, and medicine (and you know those sciences work because they cure our infections and give us computers), and 3) evidence clearly shows that the central tenets of homeopathy – for example, that like cures like and dilution increases potency – are just plain wrong. Belief in homeopathy appears to be driven by expectancy effects and the placebo effect.

Or as Tim Minchin puts it more eloquently in this animated beat poem:

“Alternative medicine has either not been proved to work, or been proved not to work. Do you know what they call alternative medicine that’s been proved to work?... Medicine!”

Have you ever wondered what a homeopathic emergency room would look like? Comedy duo Mitchell & Webb give us an idea in this brilliant sketch. And in this video, we learn how “double-blind” studies work in homeopathy: you do the study, and then you don’t look at the results…. twice!

Progress was slow for a long time, but many people now recognize that homeopathy is not innocuous nonsense; it’s dangerous nonsense that kills people every year by steering them away from real treatments. This has led to positive developments like the European Manifesto against Pseudo-Therapies, which is worth clicking on and reading.

4. The Secret

“This was… the usual New Age nonsense… a mush of psychobabble, self-help tips, pseudo-scripture, and Chicken Soup for the Soul.”

– Connie Willis, Inside Job

Ah, The Secret: a bowl-you-over-with-bullshit kind of book. It’s founded on the idea that positive visualization will make good things appear in your life, and it repeatedly implies that if your life is beset by misfortune and misery, you’re bringing it on yourself by not thinking positively. Like many other brands of woo, it misuses quantum physics to advance its claims (classic, I tell you!), and has an ugly flipside.

In this piece, two prominent psychologists analyze the dreck peddled in the book, paying special attention to why people are drawn to it. And in a no-holds-barred analysis, this piece explains how the doctrine is founded on a core delusion.

5. Psychics, Mediums, Soothsayers, Clairvoyants, and Psychokineticists

(these are a few of my least favorite things)

This, ladies and gents and non-binary folks, is the NBA All-Star team of bullshit.

Bilking people out of their money in exchange for false hope is nothing new, of course. Debunkers like Harry Houdini and The Amazing Randi did an excellent job of unmasking con artists in their day.

If you’re a student of psychology, make sure you get to know The Amazing Randi. You can start with this great introduction. You should also check out this documentary about his stellar career and riveting personal life. You can find his books here.

“Spreading her pernicious astral-plane-Higher-Wisdom hokum and bilking her benighted audiences out of their cash.”

– Connie Willis, Inside Job

If you want a bit of a mind-bender, try this brilliant Hugo award-winning novella by Connie Willis, the most decorated science fiction author of all time. Willis weaves seances, skepticism, and romance into a superbly crafted, tightly structured tale that revolves around a central paradox and finishes with a satisfying ending.

Psychology Students: Could You Be Missing the Point of Psychology?

Are you a psychology student who believes in some of this woo-woo? If so, forgive me, but there is a sense in which you’re missing the animating spirit and methodological backbone of your discipline. The progress of psychology – or, one might argue, the point of psychology – is to explain the human mind in a natural way, one that does not rely on entities or forms of causation for which we have no evidence. Psychology succeeds precisely to the extent that it’s able to naturalize the mind and bring it under the purview of science.

The goal is a grand one: to understand the mind in all of its beautiful weirdness – déjà vu, the placebo effect, nervousness-induced itch, false memories, synesthesia, lucid dreaming, near-death experiences – in a fully natural way that doesn’t violate any known laws of the universe, doesn’t rely on miracles, and doesn’t postulate entities that aren’t needed to explain the phenomena at hand. If you let in spirits or divination or personalities forged by planetary pulls, you’ve given up before the game really got started.

The good news is that it’s never too late to begin thinking of the mind this way. Your brain is a squishy, wet computer that obeys the laws of physics and was shaped by the blind algorithmic process of evolution. Come on over to the dark side! You won’t miss the woo-woo that much, I promise. There’s awe and grandeur in this naturalistic view of the mind.

Plus we have cookies.

Sources for Detecting Bovine Stercus

Carl Sagan, who was too much of a gentleman and a scholar to call it “bullshit”, penned this well-known essay on how to detect baloney. It is timeless reading for anybody figuring out how to think about the world. Also helpful are Sagan’s book The Demon-Haunted World and this young adult book about how we know what’s true.

If you’re interested in one-stop debunking sources, you might consider Skeptic Magazine and the Center for Inquiry.

If you’re especially curious about psychology, here’s a classic on 50 great myths of popular psychology.

What about superstitions? You might enjoy this short educational video on the subject, even if you’re only a little stitious yourself.

Or if you have questions about the psychology of conspiracy theories, check out this funny video compilation and this scholarly paper on conspiratorial thinking.

And finally, because science is awesome, we now have research on how people react to pseudo-profound bullshit. (Interestingly, being sad appears to make people more skeptical of it. And it seems that the source of the bullshit also matters).

Where to Go From Here

I would find it gratifying, I admit, if this post served as a starter kit for students to think more critically about psychology-adjacent woo. The discussion in each section is short and superficial, but there are many breadcrumb trails for you to follow and do some deeper reading. Failing that, I hope the songs and videos at least make you chuckle.

Please remember: in evaluating claims about the mind, anecdotes don’t count. All the evidence we adduce has to be guaranteed kosher – untainted by confirmation bias, not driven by the placebo effect, free of the million other mistakes we make when we try to comprehend the world with our fallible, meaning-hungry minds. This is why we can’t count evidence that comes from personal anecdotes rather than rigorous studies with the proper scientific controls. It may sound a bit harsh, but adding personal anecdotes filtered through cognitive biases is just adding zeros.

In service of understanding the world, we’re wedded to the principle that if it isn’t supported by systematic evidence or isn’t really needed to do the explanatory work, we just don’t need it. Douglas Adams once wistfully remarked: “Isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”.

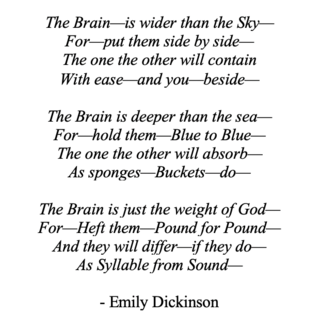

If our goal is to understand the mind, we should leave the phantoms and the wishful thinking aside. We don’t need them and we’ll be fine without them. There’s more than enough majesty and awe in the natural world – beautifully captured by Emily Dickinson in her timeless poem:

References

[1] Lewis Carroll’s version was: “If you set to work to believe everything, you will tire out the believing-muscles of your mind, and then you’ll be so weak you won’t be able to believe the simplest true things.” (Letters, vol 1, p. 64)